What's a Sewel Convention and why did it feature in the Brexit court ruling?

- Published

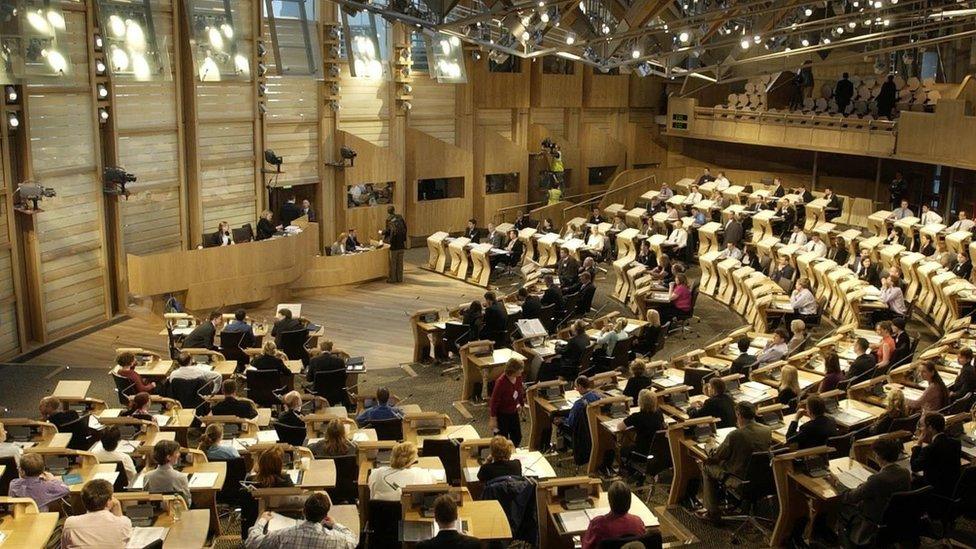

What role could MSP now have following the Supreme Court ruling?

A 97-page document explaining why Supreme Court judges rejected UK government arguments regarding Article 50 mentioned the words "Sewel Convention" 18 times. So, what does Sewel mean and why is it important to the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland administrations?

What is the Sewel Convention?

In July 1998, the UK government announced that a convention would be established so that Westminster would not normally legislate on devolved matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland without the consent of the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly or the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The devolution settlement of that time meant that power was handed to the three nations, but sovereignty was retained by Westminster.

This undertaking was subsequently expanded, and now consent is also required for legislation on reserved matters if it would alter the powers of the devolved parliaments and ministers.

A new sub-section of the Scotland Act 2016, external clearly stated: "It is recognised that the parliament of the United Kingdom will not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters without the consent of the Scottish Parliament."

Where does the convention's name come from?

The convention is named after Lord John Buttifant Sewel, a former Labour life baron for Gilcomstoun in Aberdeen. The Durham University and Aberdeen University educated 71-year-old sat on the Scottish Constitutional Commission between 1994 and 1995.

His name was used because he was the Scottish Office Lords Minister who saw through the key devolution act.

The convention has now been restyled Legislative Consent Motion (LCM) but the name "Sewel" has remained in common parlance.

At its heart, the Sewel Convention, external stated: "Devolution does not prevent Westminster legislating for Scotland, even in relation to devolved matters.

"There will be instances where it would be convenient for legislation on devolved matters to be passed by the UK parliament."

When are Sewel motions used?

It was believed that the Sewel convention allowed pragmatic solutions to be developed in making legislation in both the UK and devolved parliaments. A raft of reasons was given on when they could be used, including;

There will be occasions when it makes sense to legislate on a UK-wide basis

There may be a suitable legislative vehicle available at Westminster which would save legislative time in the Scottish Parliament

Legislating at Westminster could be an appropriate means of dealing with issues which straddle both devolved and reserved matters

Where it would be helpful to make minor and technical changes in devolved areas, for the effective operation of legislation in non-devolved areas

Where an operational role is proposed for Scottish ministers in reserved areas

In practice, only ministers of the devolved administrations can initiate them. They are tabled only after ministers and the UK government have agreed a legislative proposal which appears to require the consent of Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

How many have there been and are they ever controversial?

In Scotland, the first Sewel Motion was used in June 1999, before Holyrood assumed its full powers on 1 July. The legislation in question related to food standards and was brought by the then Scottish health minister Susan Deacon MSP.

The Scottish Parliament has used the convention some 146 times covering wide-ranging areas including;

the supply and use of fireworks

gender recognition

removing Crown immunity from planning controls

tobacco advertising

the carriage of guide dogs in private hire vehicles

and sea fishing grants

The use of the motion has been the focus of criticism in the past. In 2005, the Scottish Conservatives believed too many Sewel motions, external were being resorted to.

The then leader, David McLetchie, said that "there's more than a hint that they are being used for reasons of political expediency and in an inconsistent manner".

Why was the Sewel Convention mentioned so many times in the Supreme Court judgement?

It was important for the judges to address the convention because it was a central argument raised during the three-day court hearing into whether the UK government should consult widely on triggering Article 50.

In early December last year, the appeal case heard legal arguments from Scotland's Lord Advocate and the Counsel General for Wales.

James Wolffe, Scotland's top legal officer, said he was not arguing that Holyrood had a veto over the issue, but he insisted its consent was required because of the "significant changes" Brexit would make to its powers.

However, the UK government maintained that powers over foreign affairs such as the EU were firmly reserved to Westminster.

The Supreme Court judges concluded that in legal terms the Sewel Convention was not a key issue.

The judges said in their deliberations: "In reaching this conclusion we do not underestimate the importance of constitutional conventions, some of which play a fundamental role in the operation of our constitution.

"The Sewel Convention has an important role in facilitating harmonious relationships between the UK parliament and the devolved legislatures.

"But the policing of its scope and the manner of its operation does not lie within the constitutional remit of the judiciary, which is to protect the rule of law."

Could the Sewel Convention yet be used by Holyrood during the passage to Brexit?

It could, but as the Supreme Court judges stated its "operation does not lie within the constitutional remit of the judiciary".

From the political world there has been a hint that Sewel - as the judges put it - or LCMs, to give them their Sunday name, could play a role.

Westminster's Scottish Secretary David Mundell said of the Great Repeal Bill, which will be central to the UK leaving the EU: "I anticipate -and I do caveat it, until you see the bill - but I anticipate that the Great Repeal Bill would be the subject of the legislative consent process. I'm working on that basis.

"The bill has not been published, so you can't be definitive, but given the Great Repeal Bill will both impact on the responsibilities of this parliament and on the responsibilities of Scottish ministers, it's fair to anticipate that it would be the subject of a legislative consent process."

What is Holyrood saying about using the Sewel Convention?

Following the Supreme Court ruling, the BBC asked the Scottish Parliament whether Sewel would be used during the legislative passage to Brexit.

A spokesman said: "The presiding officer [Ken Macintosh] cannot reach a decision on whether the LCM [Sewel Convention] process can proceed until a bill is introduced to the UK parliament and a draft legislative consent memorandum has been submitted to the Scottish Parliament.

"We will not prejudice this decision by speculating in advance.

"Notwithstanding the LCM process, there are a number of ways in which the parliament can express its view on an issue including motions, debates and parliamentary questions."

So, Holyrood's presiding officer plays their role.

And what happened the last time a presiding officer was asked to deliberate on a controversial Sewel motion? Well, you only need to look into the recent past.

In December 2015, the Scottish government attempted to use the Sewel Convention to block the Trade Union Bill from applying to Scotland. However, that was rejected by the then incumbent, Tricia Marwick.

Ministers had wanted Holyrood to have a say on the UK parliament bill as it could affect devolved areas.

But those arguments were not accepted.