Tam Dalyell: a rebel with umpteen causes

- Published

He was the Old Etonian aristocrat elected to represent a mining constituency. He was the former Tory who moved to the Left of the Labour Party. He was exceptionally polite - but endlessly persistent, to the occasional exasperation even of his friends.

In short, Tam Dalyell was different. However, it is important to understand that he was not a self-conscious rebel, not one of those who choose contention for the sake of sounding different or for the sake of getting attention at all.

No, when Tam challenged power, he did so because he believed fervently in the cause he was pursuing. He believed that power unchallenged was corrosive and corrupting.

Tam is customarily categorised as a maverick. To be clear, it is a role he did not seek, at least not self-consciously. Remember that, not long after entering the Commons in 1962, he was enlisted as a Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to Richard Crossman.

Serving as an aide, particularly to such an elevated Cabinet Minister, was seen then - and is seen now - as the first step to Ministerial office. Frankly, Tam would have liked to be a Minister. His political convictions and his determined demeanour - his torment of the Establishment - made that impossible.

I knew Tam well, encountering him on umpteen occasions over many years. As a young newspaper journalist, I covered his involvement in the 1979 devolution referendum - when a Scottish Assembly, so styled at the time, attracted sufficient support to count as a simple majority but insufficient to overcome the rule which required backing from forty per cent of the registered electorate.

Tam talked then of devolution as a motorway with an inevitable destination of independence. He talked then of the intrinsic contradictions which he saw in devolving partial power to one segment of the UK while retaining the Union Parliament at Westminster.

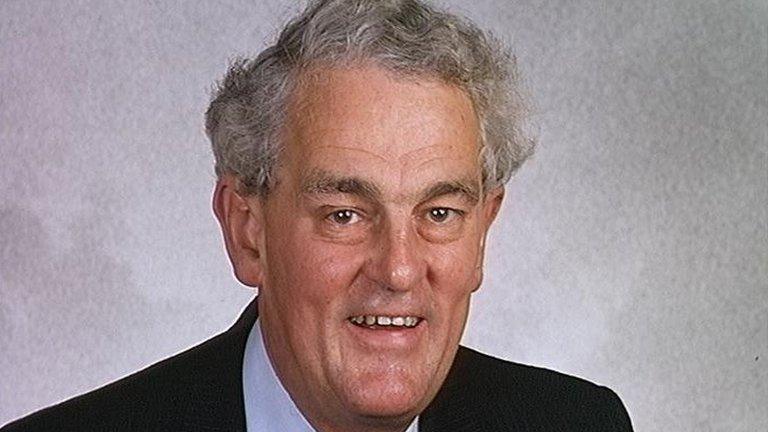

Mr Dalyell was admired for his fearless criticism of government

During consideration of the devolution Bill, the MP for West Lothian would rise magisterially to his feet in the Commons - again, again and indeed again. He invited members to presume that a devolved Assembly was in place.

He then inquired along the following lines. "How can it be right that I can vote on education in Blackburn, Lancashire, but not in Blackburn, West Lothian?"

This query was repeated endlessly, each time with an alternative alliteration of Scottish and English communities. It morphed in common understanding into a complaint that MPs from Scotland could influence English affairs but that MPs from England would have no say over devolved Scotland.

Finally, after the umpteenth such challenge, Enoch Powell rose in mock exhaustion to suggest that, in the interests of brevity, the Honourable Member might curtail his repeated inquiries to state simply: "The West Lothian Question."

And so was born the constitutional conundrum which pursued devolution then - and, to a certain extent, still does today. (Think EVEL, English votes on English laws).

'Now, Brian, look...'

Nationalists tended to respond to West Lothian: "Easy. Independence." Tam's irked Labour colleagues were wont to mutter: "Any chance, Tam, you could stop asking such an awkward question - especially when we don't know the answer?"

Much later, in the new millennium, I would occasionally invite Tam to contribute to some constitutional debate or other.

Often, he would agree. Occasionally, he would quibble at the transient nature of the discourse. He would say to me: "Now, Brian, look." (You have to imagine his deep, dry, modulated tone when you contemplate this).

"Now, Brian, look… I wrote a book of some six hundred pages on this subject. I couldn't possibly condense my thoughts in the manner you describe." B

y which point, his face would be subsiding into a mischievous grin. Or even the booming laugh with which Dalyell of the Binns would sometimes perturb the citizenry.

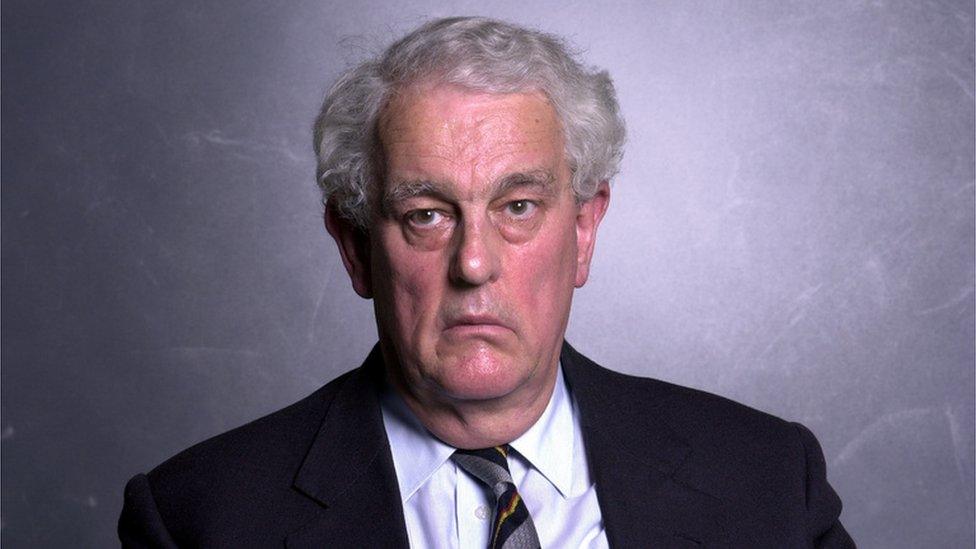

Mr Dalyell was elected to the House of Commons in 1962

But there was more, much, much more to Tam Dalyell than simply his involvement in the Home Rule debate, trenchant though that was. He was a rebel with umpteen causes - frequently focusing upon global issues with his trademark zeal.

For a spell, it seemed as if Margaret Thatcher could scarcely stand up in the Commons without Tam Dalyell pursuing her over the fate of the Argentinian warship, the Belgrano, during the Falklands conflict.

Tam was agin the Gulf War, he questioned Libyan involvement in the Lockerbie bomb, he challenged his own party's Prime Minister over the invasion of Iraq. To be clear, these are but a few, a fraction, of the causes he followed.

His critics - and there were one or two - say he was too inclined towards conspiracy theorising. They say that he was prone to pursuing a topic even when repeatedly advised that the facts pointed another way.

But Tam Dalyell paid little heed. He believed he had a duty to challenge authority, to question, to interrogate. A duty in the public interest. With no personal gain for himself; quite the reverse.

Valiant campaigner

In Linlithgow today, his former constituents told of another Tam, of the diligent, dedicated MP who would support local events, who would pursue local issues. Who was a helping hand.

Me? I remember a valiant campaigner for truth and justice. Some said he was quixotic, tilting at chimerical windmills. Others, even among his critics, saw him as a one-man check upon executive power, upon intrinsic Establishment tendencies towards chicanery and deceit.

He was the necessary irritant which prompted the political machine to work. He was the seemingly abrasive sandpaper which, eventually, helped smooth the wood to perfection.

Politics has enough, more than enough, of the complacent and the complaisant. We could use more like Tam - if such is imaginable. More like the man who summed himself up in his autobiography, entitled "The Importance of Being Awkward."

He will be missed. My sympathy to Kathleen and his family.

- Published27 January 2017

- Published26 January 2017