Duel of the popular mandates at Holyrood

- Published

MSPs voted to oppose the triggering of Article 50

Perhaps it was theatrical envy, but Ben Jonson was faintly acerbic about Shakespeare, noting that he had "small Latin and less Greek".

(Maybe so, Ben, but who watches Volpone today?)

My own Hellenic expertise fails to ascend even to the level of the Bard of Avon. But I think I am right in saying that the word "democracy" has a Greek origin. From "demos", the people, and "kratia", power.

Perhaps Greece is not, itself, the power it once was. If the glory that was Rome has crumbled a little, so too has the majesty of Athens.

But, still, Greeks can consider themselves the progenitors of people power. Despite those ancient origins, the very concept remains under scrutiny. Or, more precisely, repeated contest and dispute.

There are debates about "kratia", about the extent of elected power. Just ask President Trump in his battle with judicial verdicts.

But, in Scotland and elsewhere, there are also debates about "demos". Which people? Whose mandate? Scotland alone? The United Kingdom?

If anything, the controversy which has attended Brexit straddles both elements. What exactly were people voting for on the 23rd of June last year? How is that verdict to be interpreted and implemented?

And, as was illustrated at Holyrood today, which popular mandate takes precedence? That of the people of Scotland - who voted to Remain? Or of the people of the UK - who voted to Leave?

In essence, such has always been the fundamental nature of the fault line in Scottish politics. Where does loyalty lie? Not in emotive terms only but in practical implementation?

For the SNP, the question is decided. They take their orders, they tell us, from the people of Scotland. Not the UK, which they seek to end in its present form.

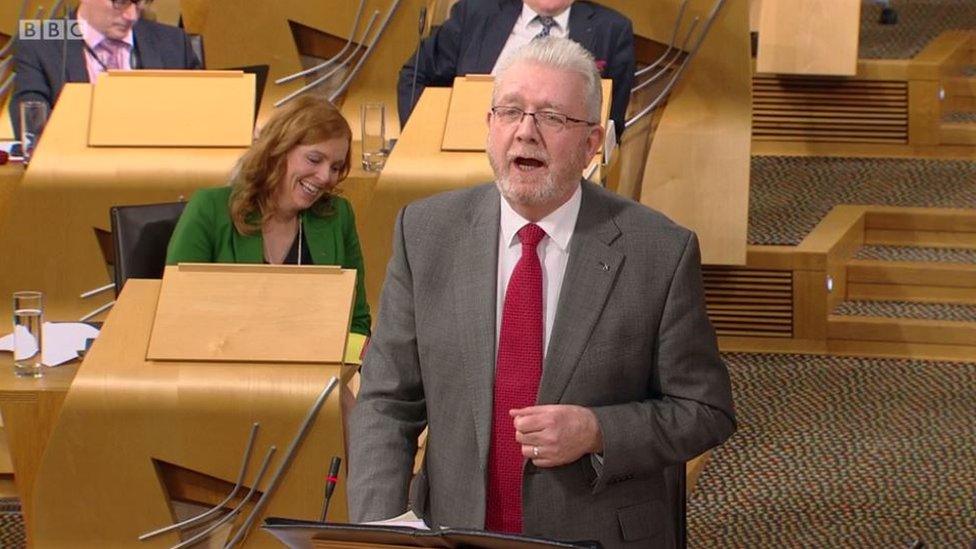

Mike Russell said "Scotland's voice" was being ignored

In a well-framed speech, Scotland's Brexit Minister Mike Russell drew attention at Holyrood to what he characterised as Scotland's voice.

The people of Scotland had voted to remain. The Scottish Parliament had endorsed that, repeatedly. The Scottish government had offered what he called a compromise in a White Paper. Only one Scottish MP - the Secretary of State - had voted for Article 50 in the Commons.

As I write, Holyrood is about to vote against the triggering of Article 50 on the basis, largely, that "Scotland's voice", as described by Mr Russell, has seemingly been ignored.

This is plainly an iterative, cumulative strategy. Scottish government ministers argue that they are giving the UK government every opportunity to pay heed to "Scotland's voice".

Should those requests be rejected, then…

Well, you know the answer - although Mr Russell tactfully avoided spelling it out. It would be "choice", otherwise known as indyref2. Nicola Sturgeon is not, yet, absolutely set on such an outcome. But it seems highly unlikely that the UK government can produce anything which would be regarded by the SNP as an acceptable compromise.

Ross Greer and John Lamont took quite different sides in the Article 50 debate

So "demos" for the SNP means the Scottish people. Ditto the Greens. Ross Greer pursued a theme which has also been deployed by the SNP.

This was to argue that the UK was changing, was moving in an inimical direction. That Scotland should consequently consider independence afresh. The alternative, said Mr Greer, was "holding hands" with what he styled "the bigot in the White House" in search of a trade deal.

The Tories have little trouble with this question either. John Lamont said the issue of Scottish membership of the EU does not presently arise. The question on the ballot paper was about the UK.

The SNP, he said, should accept the verdicts in 2014 and 2016. They should become "born again democrats".

For the Liberal Democrats, Willie Rennie suggested that the verdict of the people in 2016 did not contain nor direct the terms of the eventual deal to leave the EU. The people, he suggested, should be asked again for their verdict once those terms are known.

Intriguingly, just as he was speaking, MPs were hearing a promise from the UK government that there would be a vote in the Commons post negotiation - but before a decision is taken by the European Parliament. However, it was swiftly stressed this did not mean Brexit could be halted. It meant leaving without a deal - or with the deal on the table.

Lewis Macdonald said he accepts that the UK will be leaving the EU - but Willie Rennie wants another referendum

Which brings us to Labour. It will be evident to all that they have faced a substantial degree of internal dispute and discontent over Brexit.

It is easy to chide - although I am inclined to think of the divisions which have confronted various parties down the decades: Labour under Wilson; the Tories under Major and at other points; the SNP when they moved from Euro-scepticism to Scotland in Europe.

However, Labour's present turmoil seems notably acute, undoubtedly reflecting the wider travails over the party's policies and direction.

Today at Holyrood Labour rather neatly found a solution. Or at least a stratagem.

Lewis Macdonald said his party would not presently favour the triggering of Article 50 on the grounds that the terms were unclear and thus unsatisfactory.

Thus they took a different line from Jeremy Corbyn - and instead fell, for this debate at least, into line with majority popular opinion in Scotland (although not perhaps in some former Labour stronghold areas.)

However, Mr Macdonald also said his party opposed a further referendum on independence. A plague on both your houses.

Bet Ben Jonson wished he'd come up with that one.

- Published7 February 2017