What impact might Brexit have on Scotland's future?

- Published

Allan Little finds that Brexit and the prospect of a second Scottish independence referendum have put the future of Scotland in focus again

A decision by voters last June to end the UK's membership of the European Union has put the spotlight back on Scotland's constitutional future. So what now for the country? Allan Little looks at some of the big questions needing big answers.

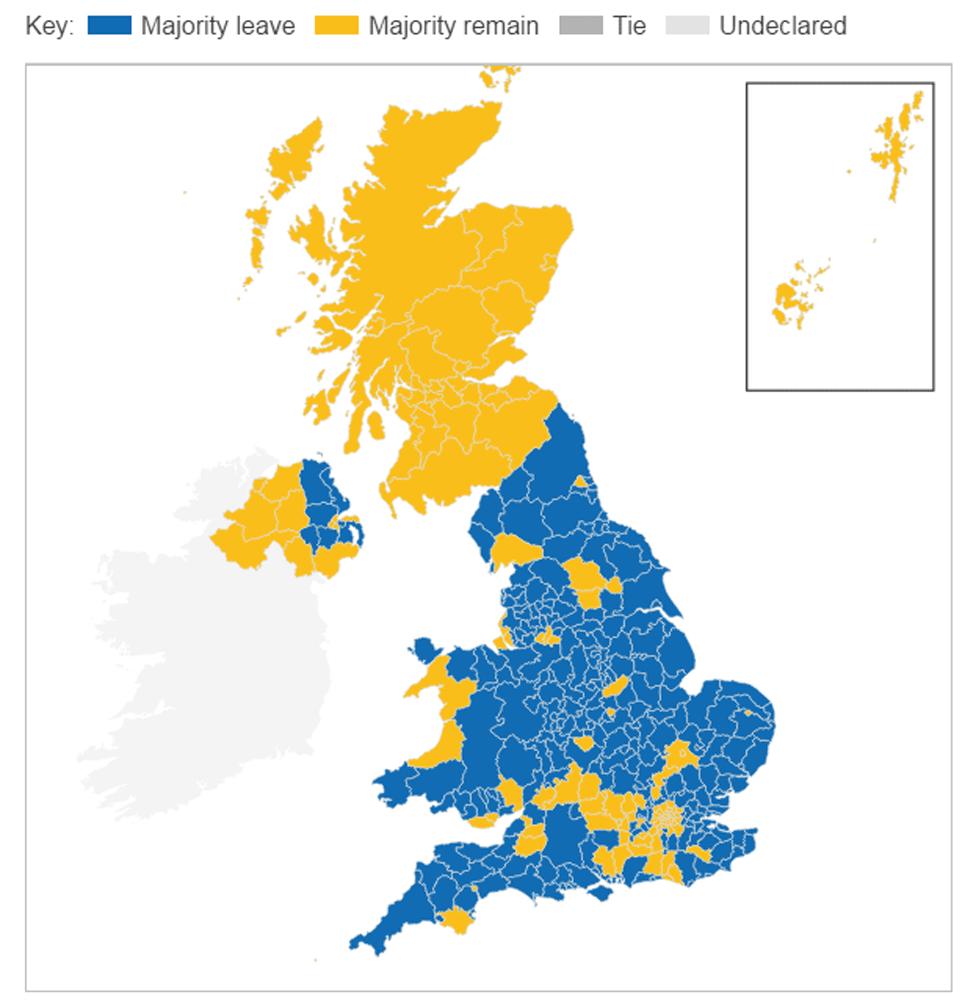

Look at the map. The results of the Brexit referendum make the island of Britain look like two quite distinct countries - voting for different values, embracing different, indeed mutually-hostile, visions of the future.

Measured by the way it votes, Scotland has been tacking away from the rest of the UK at least since the 1980s. But the divergence has never looked as stark as it did the morning after the EU referendum. Not one of Scotland's 32 electoral regions voted to leave.

The SNP believes the mandate for a second referendum on independence is solid: a UK outside the EU is not the UK that a majority of Scots voted to stay in in 2014.

The map of the UK following the EU referendum vote in June last year

But putting the question to the public as early as 2018 or even 2019 carries huge risks for Nicola Sturgeon. Many nationalists remain confident that the long-term direction of travel is towards independence. It is driven in part by age demographics: the younger you are, the more likely you are to favour an independent Scotland, external.

The polls, though, have not shown a dramatic change in the level of support for independence: the question still divides the country roughly 50-50.

Ideally, the first minister would be looking for support for independence to rise perhaps to 60% and for that to be sustained and stable over many months before putting the question again. That doesn't seem likely in the short term. There hasn't been an indisputable "post-Brexit bounce" for the independence argument.

And to lose a second referendum so soon after the last one would surely close the question for the foreseeable future.

Brexit also changes the independence proposition. There could be no rerun of the 2014 case in all its fine detail. Brexit puts us in new territory.

Take the question of the border. The "No" campaign last time raised the spectre of passport controls at Gretna Green and customs checks on the Tweed. There wasn't much credibility in this argument - though it undoubtedly scared many.

Back then, the proposition was that both Scotland and the UK would be inside the EU single market, where there is free movement of goods services, capital and people.

That will not be the case when the question is put next time. If Scotland stays in the EU, or enters as a new member, while the rest of the UK is outside, will a border descend across the island of Britain for the first time since 1707? No one knows. The question has scarcely even been asked, never mind answered.

The border question is hypothetical for Scotland, but it's real and urgent for Ireland. The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic will soon become the border between the UK and a trading block of 27 member states that stretches all the way to the Black Sea.

What currency might an independent Scotland have?

Once Britain is importing goods from around the world, goods that might not meet EU import rules, how do you stop those goods that have come to Britain from around the world moving across that border and into the EU single market? The other 27, eager to protect their own producers from unfair competition, will want an answer to that before agreeing to a Brexit deal.

Both Britain and Ireland say they want to keep that border open. No one yet knows how that can be achieved. But if it is achieved, it would create a precedent for Scotland.

Glasgow-based Irish journalist and academic Peter Geoghegan says: "There's an awareness growing that a solution for Northern Ireland could also have ramifications in Scotland.

"If a solution is found that keeps that border open, then a pro-independence campaign would be able to say - well you did it for Northern Ireland, why can't you do it for Scotland?"

Two further obstacles loom large in the building of a new independence case: the currency and the deficit. What currency would an independent Scotland use now that sharing the pound would surely no longer be an option? And how would Scotland seek to close the gap, in the first few years of independence, between what the country spends and what it raises in taxation.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon spoke to journalist Allan Little for his documentary "Europe: Scotland's Dilemma"

Nicola Sturgeon told me: "I absolutely accept… that in the context of another independence referendum. Those of us who advocate independence have a duty to answer those questions. And that includes issues around economic sustainability and security and around the currency.

" You'll think I'm being difficult but I'm not going to jump and get into detailed discussions just now."

But if the risks of going too soon for Ms Sturgeon are too high, think how Brexit also changes the "Better Together" proposition.

Defending the Union next time round will be quite different too.

Look at the map again. Amid much pro-Brexit talk of "the will of the people", the pro-Union campaign will be open to the charge that they are perfectly ready to disregard the will of the Scottish people in the interests of keeping the UK together; that it is, in effect, right and proper that Scotland's democratically-expressed desire to stay in the EU should be disregarded and overlooked because Britain as a whole voted to stay out.

Who is risking what?

Good luck with arguing - against that new stark reality - that the Union is a partnership of equals, as David Cameron did in 2014.

Ruth Davidson, the leader of the Scottish Conservatives, disputes this.

She says: "It puts the SNP, not us, in the difficult position because they will have to argue that it's wrong for Scotland to send 59 MPs to Westminster, where they're ignored, and that instead we should be sending six MEPs to sit in a [European] parliament of 700 members, where somehow they'll have a much greater say over what's happening."

The UK government has already agreed that it would be wrong for Scotland to face another vote before the terms of Brexit are known, because this would be, in the words of the prime minister, "voting blind", even though voting blind on Brexit is precisely what the government she was a prominent member of asked us to do last June.

And they will have to argue, simultaneously, that leaving a trading block and single market with its largest and closest neighbour is the height of folly in Scotland's case, but represents exciting and bold new opportunities in the case of the EU.

The UK that the pro-Union campaign asked us to stay inside was governed by a pro-EU coalition. It will be much easier for the independence campaign, next time round, to argue that the real nationalists - the real separatists if you like - are not in Scotland at all, but in control at Westminster. That too is quite new.

Bosses at a shortbread-making factory in West Lothian worry about trade tariffs post-Brexit

Will there be a referendum in the next two years? Constitutionally, Theresa May has the legal right to block it. And the polls certainly suggest that many view the prospect of a new fight on the constitution with weary scepticism.

But the risks are obvious to anyone with a passing familiarity with the last 40 years of political history in Scotland.

In 1979, a pro-devolution campaign could scarcely muster sufficient public support for a weak, largely toothless Scottish Assembly. In that first referendum, a little over a third voted yes, a little under a third voted no, and a third stayed at home. Just 18 years later, there was overwhelming public support not just for an assembly but for a full Scottish parliament, external with primary legislative powers.

What brought about that change in public sentiment is obvious: a sense that Westminster was imposing on Scotland unpopular policies for which there was little, and steadily diminishing, support in Scotland, and for which there was, in the parlance of the day, "no mandate".

Successive UK governments, under Margaret Thatcher and John Major, argued that there was indeed a mandate, and that its was based on the popular will as expressed across the whole of the United Kingdom.

Theresa May's government is walking that path again - this is what Britain voted for, so Scotland must live with it. The risks are surely clear.

- Published18 March 2017