Mutual suspicion over the Great Repeal

- Published

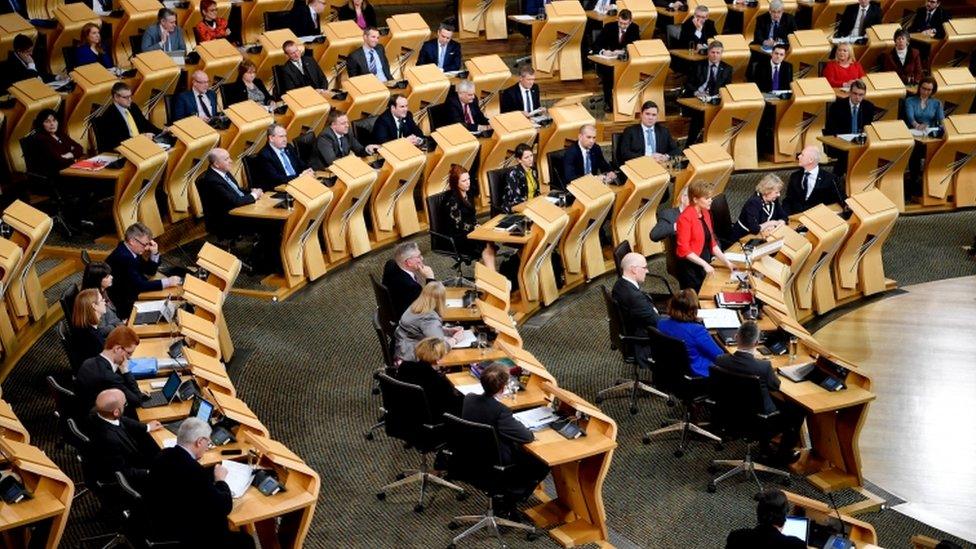

Nicola Sturgeon fears that not all powers over agriculture and fishing will return to Holyrood after Brexit

Parliamentary exchanges customarily assume a tone, a colour of their own. Perhaps the leitmotif is indignation, authentic or otherwise.

Perhaps it is consensus, when members commonly recognise that they have a task to undertake. Perhaps, again, it is tension, when a significant vote looms. Or joviality, when a respected member is on form, or Christmas is near.

Today, at Holyrood, the emblem was suspicion. In part, this was reflecting the broader atmosphere created by Brexit with its attendant issue, independence. Each party, each leader, wonders what the next step will be from rivals.

In part, that arises from older enmities. Holyrood's two largest parties are now the Scottish National Party, with a long-nurtured policy of independence, and the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party with……well, study the name.

So when those parties are responding to the Great Repeal Bill, it is inevitable that there will be mutual suspicion.

'Power grab'

The Tories reckon that the SNP will seek to turn everything, anything, into a further demand for independence. The SNP reckon that the emboldened Tories are seeking to delegitimise Holyrood while stressing the role of the UK Parliament and government.

Each side, of course, strenuously contests the claims delivered by the other.

But suspicion persists. Under questioning from Patrick Harvie of the Greens, the first minister told MSPs that she reckoned the Tories, in the shape of the UK Government, were pursuing a "power grab" in the Great Repeal Bill.

Today we got the White Paper presaging the G.R.B. Ms Sturgeon did not like what she read.

The eventual Bill will proceed by repatriating the acquis communautaire, the accretion of EU law, firstly to Westminster and thence to the devolved legislatures. David Davis, the Brexit Secretary, says Holyrood will end up with more clout.

David Davis has insisted he wants more devolution after Brexit, not less

So why the suspicion? It's that route map, discussed here yesterday. Ms Sturgeon suspects that the EU leg of powers presently devolved, such as agriculture and fishing, may return initially to Westminster - and might get stuck, to some extent.

Mr Davis and other Conservatives say that is nonsense. They say agriculture and fishing will be devolved - but within a broader UK framework, replicating to some extent the common standards current promulgated by the EU.

That will allow, UK Ministers argue, the maintenance of a UK market in food products. It will help the economy, they insist. Scottish Ministers remain, well, suspicious.

Might that suspicion extend into Holyrood action to thwart the process of Brexit? It might, although we have yet to learn the full extent to which the Scottish Parliament will be involved.

Cannot get clarity

Mike Russell, the Scottish Brexit Secretary, tells me it is presently unclear whether there will be a requirement for a full Legislative Consent Motion (LCM). He believes there will, but says he cannot get clarity from his UK counterparts.

And if there is such a need? Government officials indicate that there might indeed be objections lodged. At the very least, they say that Ministers would be very reluctant to sanction the proposals to distribute powers in their present outline form.

The notion of an LCM is founded upon the earlier Sewel Convention, now enshrined in statute. But, then, the Supreme Court reminded us that Westminster remains sovereign and that Sewel, even enacted Sewel, was not a "legally enforceable obligation".

However, their lordships also noted that conventions can have a part to play in parliamentary and governmental politics. Just not a justiciable one.

The UK government, for example, may think it politic to give Holyrood its place. Not, however, anything approaching a veto.

More on this to come. Much, much more.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published28 March 2017

- Published27 March 2017