Election 2017: How the battle is different in Scotland

- Published

With the UK heading for an unexpected general election on 8 June, what could it all mean in Scotland? Here, I examine some of the factors which could affect how the election will pan out.

Is anyone up for this?

The UK is heading for a shock snap election

Even in an age where political shocks are becoming increasingly routine, Theresa May stunned the country when she announced a sudden charge of heart - she would now call for a general election.

Each of the parties immediately said they relished the opportunity to put their arguments across - it remains to be seen if the electorate are quite as enthusiastic.

But while Mrs May has pitched her election as one driven primarily by Brexit and the need for a Westminster consensus, the vote will take on a very different air north of the border. Here, independence will be as big an issue as Brexit, and the Tories are fighting as an underdog rather than an odds-on favourite.

Last time round

The SNP came close to sweeping the board in 2015

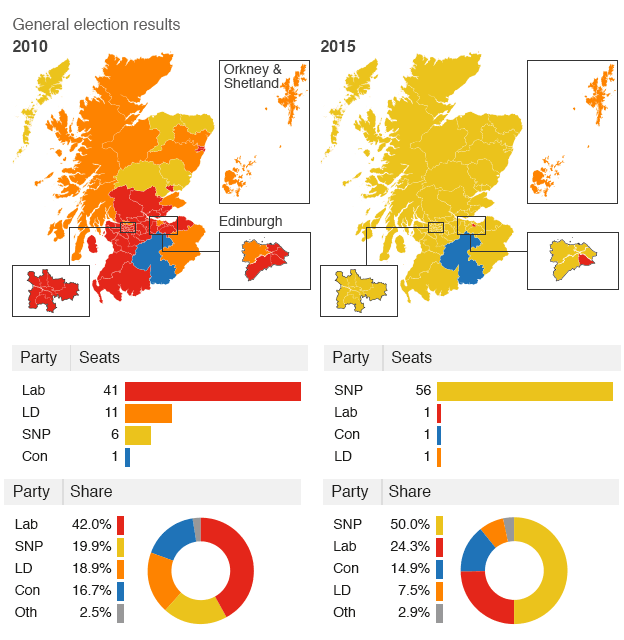

2015 was not a long time ago, in real life. But in the weird world of politics, the UK went into that election with David Cameron, Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband leading major parties. The SNP had six seats at Westminster, Labour had 41 in Scotland, and the UK was a committed if crotchety member of the European Union.

Politically, it feels like it's been a lifetime. Or, perhaps, a generation.

What will colour events this year is that the 2015 general election in Scotland was remarkable. Riding a wave of popular support in the wake of the 2014 independence referendum, the SNP won 56 out of 59 seats, leaving its rivals in the Conservatives, Labour and the Lib Dems with just one apiece.

Judged against that return, the SNP could hardly do better in the looming election; most of the other parties could barely do worse.

That is, of course, part of Mrs May's strategy. Her Tories seem all but certain to improve their return, while her main rivals look set to lose ground. Opponents call it opportunism; she'll let them call it whatever they like, as long as she wins.

But the SNP is still riding high in the polls - and with Westminster's first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all system it is confident of doing well again. After all, the party "only" needed 49.97% of the vote in 2015 to come close to a clean sweep.

If you plug the results of the 2016 Holyrood election into one of those Westminster seat-calculator machines, external (with all the caveats necessary for such an approach - we're strictly looking for general guidance here) the SNP's constituency result of 46.5% would yield 55 seats (losing one to the Tories). Its regional list result of 41.1% comes out with 51 seats, losing ground to the Tories and Lib Dems.

Under normal circumstances that would be a be a brilliant result, a thumping win with 50-odd seats, but it could still look like a loss (and be painted as one by Mrs May) if it's anything less than 56.

Equally, if the Tories go home with three seats, they'll have trebled their return. They'll be able to paint it as a swing towards their position, and away from the SNP and independence.

There is a challenge for the Tories in fighting as heavy favourites south of the border and as underdogs in Scotland, but they're very much up for the fight. Labour, meanwhile, is probably the party least keen on an election - but again, it only needs to hold on to one seat to prevent itself from going backwards.

Brexit

Scotland will have had votes on Europe, the UK and Holyrood inside just over a year

Theresa May was very clear that this election is about Brexit; it's about securing a solid mandate for herself and her party to take into the exit negotiations with the EU, so she doesn't have any domestic worries gnawing away at the same time.

Nicola Sturgeon says that's a "huge political miscalculation" in Scotland, which on the surface seems obvious given every council area in the country returned a majority for Remain.

But like it or not, Brexit will factor at all sorts of levels in the coming contest.

There were after all a million Leave voters in Scotland, from all across the party spectrum - including a decent number in the SNP. There's also a lot of competition for Remainer votes, with the Lib Dems pitching themselves hard as the pro-European party, alongside the SNP and the Greens and Scottish Labour.

On the other side, Theresa May's Conservatives are effectively running as the party of Brexit, but could there be room for UKIP to challenge?

It seems unlikely - the party picked up 2% of the vote in the latest Holyrood elections, and its sole representative, MEP David Coburn, finished fourth in the Falkirk race in 2015 on 3% of the vote. It appears Mr Coburn might stand again this year - understandable given his job in Brussels is disappearing - but his chances of winning a seat still look slim.

Independence

The Scottish government was already angling for a new Scottish independence referendum

The other constitutional elephant in the room is of course independence.

If the election is seen as a referendum on Brexit in England and Wales, independence will undoubtedly play a major role in the Scottish campaign.

The Scottish government insists the move to an election footing makes no difference to its current claims for a second referendum; it says it already has a "cast iron" mandate and doesn't need another one. But there will inevitably be an impact, in the first instance because there won't be a UK government to negotiate with.

But while a general election win will solve many problems for Mrs May, the issue of Scottish independence is unlikely to be one of them.

As noted above, her calculation is that the SNP probably won't be able to hold on to all 56 of the seats they won last time round. She can then paint that as the SNP in decline, the people rejecting their doctrine for independence, and so on.

There's already been some ground prepared for that; Ruth Davidson saying that Scotland has passed "peak Nat".

However, while the SNP will probably lose a few seats, from its present position it's still likely to win the majority of them (so 30 or more). And given it's inconceivable the party won't make any mention of independence at all in campaigning, it can argue that is a mandate for indyref2. Oh, and there will still be a pro-independence majority at Holyrood.

So we will end up exactly where we were in the ancient days of March 2017, with the London and Edinburgh governments arguing over who has a mandate for what.

Almost more important than how the parties approach the vote is how the electorate approach it.

If Scottish voters treat this election as a referendum on independence, a lot of seats could become straight fights, two-horse races between independence-supporting versus unionist parties.

The Tories established themselves firmly as the defenders of the union with their 2016 campaign. Labour has realised this, and has been working hard recently to burnish its pro-union credentials - but it could still find itself marginalised in binary contests where identity politics dominate.

Unionist voters might ultimately pick the party most likely to beat the SNP - and in many cases that might fall to the Tories.

Who's standing?

Most of the 56 SNP MPs elected in 2015 will run again - with a couple of exceptions

In some places it's a chance for fresh faces; in others, experienced campaigners will battle on.

With such a snap election, there isn't time for lengthy candidate campaigns and hustings. Labour hope to have a list of candidates out next week; it will be signed off by the executive council, but it's basically hand-picked by the leadership.

One question will be, which former heavyweights can be coaxed back into the contest? Could Labour bring back the likes of Margaret Curran, Douglas Alexander or even Jim Murphy?

Across much of the field, the incumbent MPs elected in 2015 will stand again. The three non-SNP members, Ian Murray, David Mundell and Alistair Carmichael have all confirmed they'll fight for their territory again.

Many of the SNP's successful candidates are also gearing up to campaign again, including popular figures like Mhairi Black, who at one point suggested she wasn't enjoying life at Westminster, external. SNP officials say they can see no reason why most sitting MPs wouldn't run again.

But there are a few familiar faces who won't be standing, at least for the parties they did last time; like Natalie McGarry and Michelle Thomson, who now sit as independents amid being linked to separate police investigations. Several activists have already put themselves forward to replace Ms McGarry on the Glasgow East ticket.

Business as usual?

Business will continue at Holyrood as usual during the campaign

Politics has been anything but normal in recent years, but some things will continue unaffected by the electoral turmoil.

Holyrood will continue to sit throughout the UK election campaign, despite the fact a few MSPs may be seeking seats at Westminster. Scottish Parliament officials have also confirmed that the UK vote will not affect the timetable for the next Holyrood election, in 2021.

There's also the matter of local authority elections on 4 May, which is likely to be days away from the start of the formal Westminster campaign. Parties may indeed seek to use them as a springboard for the general election weeks later, to build momentum.

But of course, elections increasingly are business as usual in Scottish politics. The general election will be the seventh vote inside the span of three years and one month; the joke is that polling stations are occasionally used as primary schools too.

That could have an impact in itself. Voters have heard a lot of politics lately, and party activists can only spend so much time getting "a great response on the doorsteps". How many people turn out to vote could have a big impact on the final results.

- Published19 April 2017

- Published18 April 2017