Why has May changed her mind on an election?

- Published

Theresa May had previously argued that an early election was not wanted or necessary

For an event designed to offer political certainty, the prime minister looked just a mite unsettled. And well she might, for two reasons.

Firstly, calling a UK general election is a pretty big deal, particularly in these post coalition days of supposedly fixed term parliaments at Westminster.

In tomorrow's debate, the prime minister will, in effect, be urging her own party and her opponents to bring a premature end to her premiership. For now.

It was not a time for sound-bites but perhaps Theresa May felt the hand of history, slouched oppressively upon her shoulders.

There is a second factor at play here. Mrs May said, repeatedly and volubly, that she would not be calling such an early election. It was not necessary, not wanted and would not happen. Except now it has.

So what has changed? In essence, the PM blamed her troublesome opponents. Pests that they are, they are apparently intent on making things difficult for her. Up with that she will not put. She needs a new mandate, with fewer such nuisances in the Commons.

She argued further that Westminster remained unhelpfully divided - while the UK as a whole was eagerly pursuing Brexit in a united fashion. No, me neither.

So what is really going on? I tend somewhat to discount the argument that a fresh mandate, with a larger Tory majority, would strengthen Britain's hand in Brexit negotiations.

Perhaps it might give Mrs May and her colleagues a card or two to deploy in talks. Look upon our election, ye Euro mighty, and despair.

But, seriously, will it materially alter detailed, precise, negotiations which are due to last up to two years? Will Eurocrats bow before UK Ministers because they have more chums in the Commons? Will individual leaders of the 27?

There are other related factors - both rooted in the role of the leading opposition party in the Commons. The Labour Party.

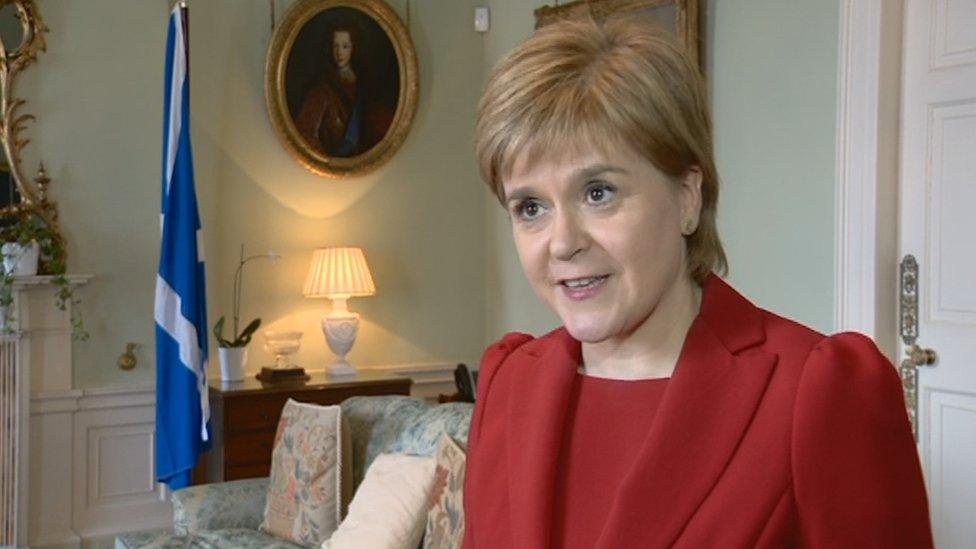

Ms Sturgeon will not fall into the trap of making the election solely a "referendum on a referendum"

Think raw, hard politics and you will agree that it is sensible for the governing party to go to the electorate when their principal opponents are seemingly in some disquiet, at least as far as the polls indicate.

Even opponents of the Conservatives grudgingly concede that it is smart politics - in blunt, Machiavellian terms - to take on Labour now.

I asked one senior Labour politician how they viewed the prospect of an election. The response? "Living the dream. Every day."

Candidate selection

My interlocutor added: "At least we should finally get rid of Jeremy this way."

To be fair, the party's Scottish leader Kezia Dugdale does not see things in such a gloomy fashion.

She says she expected an election and is ready for it, having already begun the process of candidate selection - which is now firmly in the hands of the Scottish Labour Party, north of the border.

So the PM has concluded - recently and reluctantly, she said - that now is the time to take Labour on, while seeking a mandate in her own right.

Mrs May has the example of John Major before her who struggled with a small Commons majority at a time when the EU issue was also to the fore.

Opponents of Mr Corbyn within Labour believe the election will give them a chance to remove him as leader

Mr Major opted to resign as party leader (he was fighting the anti-EU brigade) while Mrs May has opted for the broader electoral route (she is working with the Brexiteers.)

A larger majority would, it is argued, make it easier for Mrs May to steer her Brexit plans past the Commons - and thereby the Lords, by effectively obliging the upper chamber to yield to the wishes of the electorate. That, arguably, has substance.

And Scotland? Nicola Sturgeon says that Mrs May has performed a staggering U-turn, while making a huge political miscalculation. The SNP, she says, will fight to retain all of the 56 Scottish Westminster seats they won last time round.

It is intriguing to note the terms of Ms Sturgeon's response statement. She says the Tories are intent on pursuing a right-wing, hard Brexit agenda. To the disadvantage, she says, of Scotland.

She also adds that the SNP will be set on "reinforcing the democratic mandate which already exists for giving the people of Scotland a choice on their future".

Note that word "reinforcing". Ms Sturgeon and her colleagues insist they already have a mandate for an independence referendum - from the Holyrood election and from a recent vote of the Scottish Parliament.

'Peak Nat'

They will not fall into the trap of making this election purely and solely a "referendum about a referendum". What if they were to lose ground - even a fraction - from their current soaring level of 56 seats out of 59?

Ruth Davidson of the Tories says we may now have seen "peak Nat". Is she seeking to suggest, thereby, that any decline, however slight, is a reverse for independence?

And what of Ms Sturgeon's planned statement at Holyrood on indyref2, the next steps? Due next week, it may now be postponed somewhat. Or recalibrated. Or rethought. With two elections pending, the statement may not be the absolute priority for Nicola Sturgeon.

Not, to be absolutely clear, that she is in any way shelving the referendum issue. Quite the reverse. She says that her statement in Bute House demanding such a plebiscite stands.

But she argues that the Tories are primarily seeking a mandate for the continuation of austerity and for a hard Brexit approach - and must be contested, primarily if not solely, on that basis.

And the others. I found Ruth Davidson rubbing her hands, literally. She has been arguing for this approach since last autumn. She believes her firm pro-Union stance (UK, that is, not EU) can again win dividends.

And the Liberal Democrats? They look well up for it. Willie Rennie argues that his party has a clear line to advance. Across the UK, they are the ineluctably pro-EU party.

Privately, Tories concede the Lib Dems might pick up some seats on that basis. But then these same Tory strategists contemplate Labour - and they begin to think swings. And also roundabouts.

- Published18 April 2017

- Published18 April 2017