General Election 2017: The hashtags, likes and re-tweets battle

- Published

Social media has become a big part of political campaigning, as parties find new ways to reach out to potential voters. Here I look at how Scotland's parties are doing in the hashtags, likes and re-tweets battle.

It's all about you...

Each of Scotland's party leaders have a bigger following on their personal Twitter accounts than their parties do

Modern election campaigns are becoming increasingly personal - and, in some cases, presidential.

SNP events and merchandise are branded "I'm with Nicola". She's on most of her party's campaign material and don't be surprised if her face adorns the front of the SNP manifesto.

In the 2016 Holyrood election the Scottish Conservatives were more or less rebranded the Ruth Davidson For a Strong Opposition Party, while the prime minister has followed suit with Theresa May's Team in 2017.

This is reflected to an extent in their social media following - every single Scottish party leader has a significantly larger Twitter audience than their party's official page does.

On Facebook, Ruth Davidson has twice as many "likes" as the Scottish Conservative page, while Nicola Sturgeon also narrowly outstrips the official SNP page and, on a rather smaller scale, Willie Rennie trumps his Lib Dems.

This might reflect the fact people want to see a personal touch on social media - they want to hear little revelations straight from the horse's mouth, rather than carefully polished party press releases.

Spreading the word...

For most parties, Twitter remains the medium of choice for their political messaging, with Facebook - despite its much larger user base and reach - a close second.

They generally use Facebook for posting their own purpose-made material, and Twitter for sharing on-message tweets from party activists or journalists.

Twitter also offers politicians the chance to bicker with each other in a public forum. Thanks to the tagging of tweets, barely a day goes by without one leader "calling out" another over an election issue.

Other social networks are of course available. Several parties having experimented with SnapChat, leading to faintly horrifying spectacles like John Swinney transforming into a dog, external at the 2016 SNP conference.

Parties have also attempted to take to Instagram, with varying levels of effort. The SNP is by far the most active on the picture-editing and sharing platform.

The Tories don't have an account, while both the Lib Dems and UKIP have accounts but have never posted anything. The Scottish Greens have an account, which made a solitary post (about Trident) in July 2016. The one comment on it reads: "You guys need to get a social media manager."

Meanwhile, somewhat bizarrely, Labour has an Instagram account, but it's set to private, so only its nine followers can see its eight posts.

But what are the parties actually sharing on these platforms?

Smile, you're on camera...

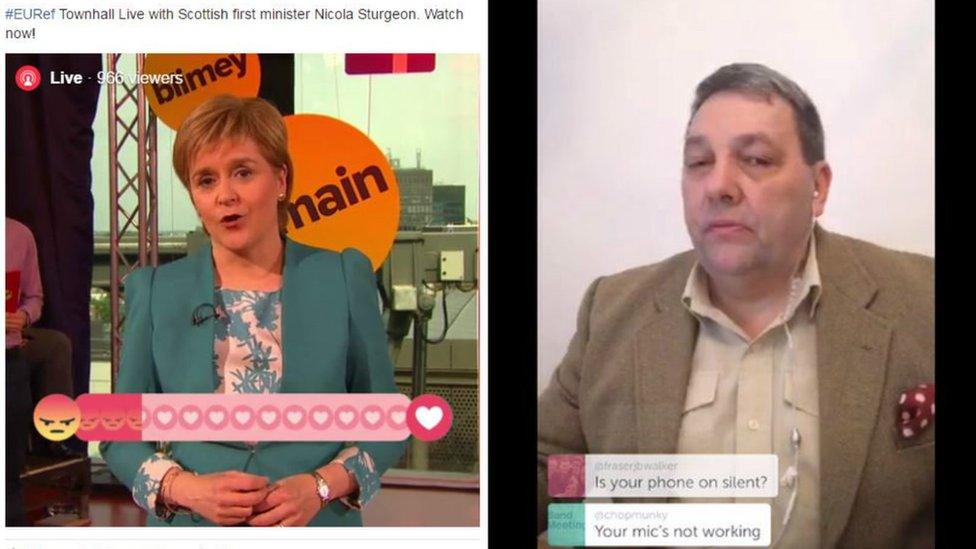

Political parties have experimented with live broadcasts - with mixed results

Looking through the social media accounts of the various parties, the presidential-style focus on leaders still dominates. Of the last 100 pictures posted on the SNP Facebook page, 82 of them were of Nicola Sturgeon; in most of the others, she was just out of shot.

The Scottish Conservatives tend to post slightly different pictures - while maintaining a heavy focus on Ms Davidson. They feature a lot of newspaper clippings with supportive stories, and purpose-made quote boxes and "memes", simple blocks of text and images (not unlike the flyers they distribute in the post) designed for widespread sharing.

Labour also post a lot of these memes, mostly promoting their own policies. The Lib Dems meanwhile feature a lot of links back to their own website, rather than bespoke material designed specifically for social media.

As mobile technology has improved and people are more and more able to stream a video without waiting 15 minutes for it to buffer, video has become a bigger and bigger part of campaigning; in particular the captioned video, which features subtitles so users can watch them without even needing to turn the volume up.

Scottish Labour have embraced this most enthusiastically, posting one or two captioned videos a day on Facebook. The SNP also regularly post videos, generally of Nicola Sturgeon speaking at events, and occasionally offer Facebook Live streams of her bigger set-piece speeches.

The Tories have also dipped their toe into the water on this front with another twist on the format: the tame interview. On Theresa May's first campaign trip to Scotland, the PM featured in a social media video being questioned by Ruth Davidson. (The Scottish Conservative leader is a former journalist, but this was not exactly a Paxmanesque inquisition).

There have been occasional attempts at live video broadcasting via Periscope and Facebook Live, with mixed results - David Coburn was infamously pranked by Periscopers inventing technical problems.

Some parties - the SNP in particular - have also been using a lot of animated graphics and gifs as an upgrade on still pictures.

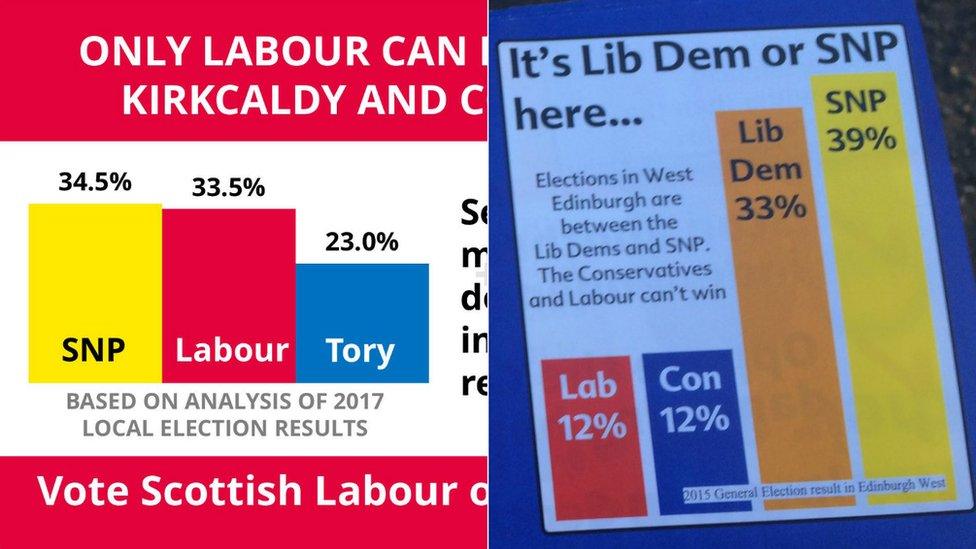

You can't beat a bar graph (apparently)...

Political parties love bar charts

For some reason, political parties really love bar graphs.

Fittingly for an election dominated by binary issues, almost every seat in Scotland is developing into a two-horse race - between the SNP, who hold 56 out of 59 of them, and whoever is most likely to beat them locally.

So the opposition parties have taken to populating their literature with graphs illustrating that "only X can stop the SNP here". The same phenomenon is also widespread in the rest of the UK, with "only X can stop the Tories here".

The idea of the bar graph is that it lends a bit of scientific credibility to such claims; after all, it's a graph. Maths must be involved, right?

Well, not always. Often these bar charts are decidedly unscientific. There's a whole community of people online who sit with rulers, pointing out the errors - and in some cases, correcting them, external.

Many don't feature any figures at all, or parties find ways of jamming in the most supportive numbers they can find - such as vote share at local elections, fought under a different electoral system, or the party's own "analysis" of figures.

There have even been examples where bar charts cited polling figures that the polling companies themselves didn't recognise, external.

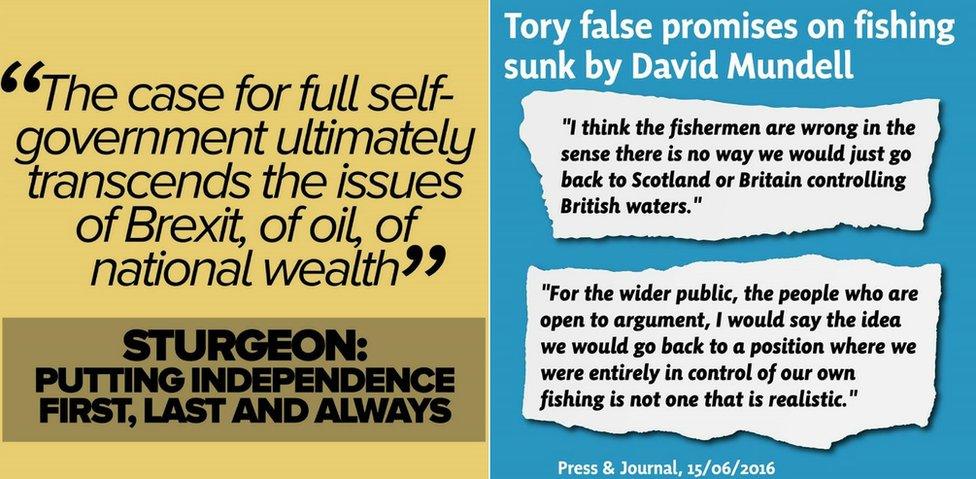

Did they really say that?...

A Tory meme attacking Nicola Sturgeon with her own words, left; and an SNP one attacking David Mundell, right

Parties love sharing inspirational quotes from their candidates and representatives.

What they love even more is sharing quotes where their opponents have put their feet in their mouths or gone off-message.

These quotes are generally missing important context or are up to a year old, but serve the simple purpose of making an opponent look bad.

The SNP are particularly fond of dredging up statements Scottish Conservative members made while campaigning against Brexit prior to the 2016 referendum, while the Tories in turn seize on just about any mention of independence from Ms Sturgeon.

Video versions are also on rise; there was one recent row over Labour cutting a video of SNP MSP James Dornan down to a single sentence, which he said left him with "nothing but contempt, external for the way they've misled the public".

We're in it together...

SNP activists on someone's lawn (left), while Tory candidates manage to combine the arts of doorstep pictures and bar charts

The classic political campaign features lots of "boots on the ground", with activists knocking on doors while local constituents dim the lights, mute the TV and pretend they're not in.

Today's candidates have found a way of combining the political tradition of door stepping with the social media tradition of obsessively sharing pictures of your own face, with the campaign trail selfie.

These generally feature a hardy band of rosette-wearing, placard-clutching activists grinning away in a cul-de-sac, with no actual voters anywhere in sight. Bonus points are awarded if it's raining heavily.

They have invariably encountered a "great response on the doorsteps".

These prospective politicians may not have parked their tanks on anyone's lawn, but they have almost certainly taken a picture there.