SNP voice 'strong and stable' opposition

- Published

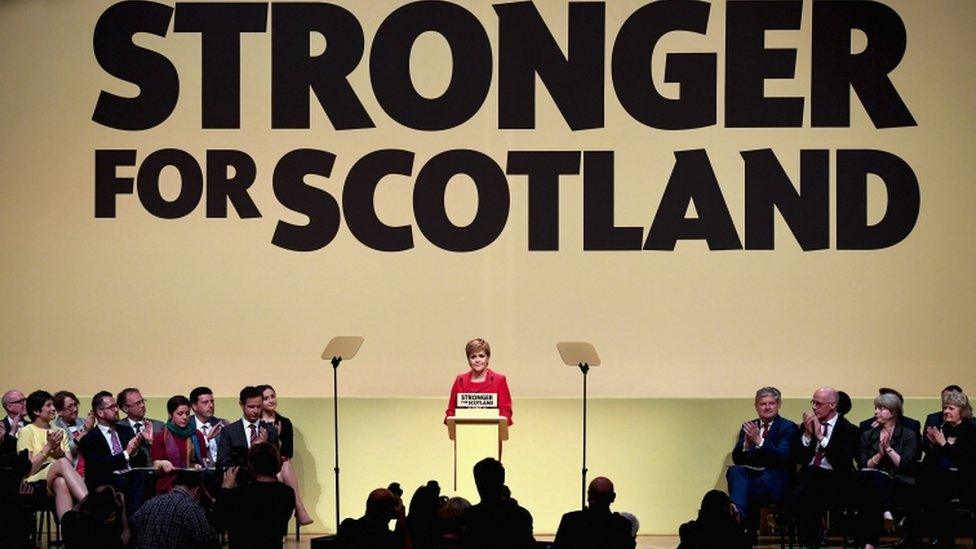

Nicola Sturgeon said that for the last two years the SNP had been the "effective opposition" at Westminster

Jollity is pretty well compulsory these days at party political events. Among the activists, that is. The wicked media sit in stoical, sceptical silence, occasionally taking notes and checking that the hall clock is right.

Of course, in days long gone by, even the party apparatchiks were immune from outbursts of glee.

Aside from the eager few or the leader's family, they too would listen, mostly mute - with only the odd nod or ripple of applause signalling that they were still awake.

But these are different times, as Lou Reed trilled in "Sweet Jane".

Today, the mere mention of a leader's name is generally sufficient to prompt an ecstatic reaction (although, to be fair, that can depend upon the leader.)

This phenomenon is observable across all parties although the Liberal Democrats sometimes affect faint disdain in their mildly iconoclastic fashion.

Activists whooped and hollered as Nicola Sturgeon took the stage in Perth

Today it was Nicola Sturgeon's turn.

As she took to the stage in Perth, the activists whooped and hollered as if they had got the date wrong and had turned up for the Southern Fried Festival instead. (Same venue, July.)

However, I was more struck by another outburst of visible contentment.

That was when Nicola Sturgeon, with an ironic grin, declared that she was in favour of increased health spending. In England.

Her Cabinet instantly got the gag. She was offering to protect the good and sensible people of England from the forecast ravages of future spending constraint.

The manifesto - Stronger for Scotland - contained plans for extra NHS spending in England

Simultaneously, she was arguing that the Scottish government (Leader, Sturgeon, N) already devoted more cash to health. (That is disputed.) And she was noting that largesse across the UK would be productive in general - and would benefit Scotland specifically through the Barnett Formula.

As she delivered these arguments, her Finance Secretary, Derek Mackay, ventured a beatific smile. If only, you could see him thinking, after a tough budget round and with future hard bargaining to come.

In general, Ms Sturgeon's approach summed up the opportunities offered by this unscheduled election. And, with less emphasis, the challenges.

For the SNP, there is a potential conundrum at the core of this election. It is intrinsic and structural.

The snag is that, however many seats they win in Scotland, the SNP cannot arithmetically form the UK government.

In response to which, Ms Sturgeon offers a constructed syllogism.

Labour look like losing, despite a recent apparent improvement in polling.

Hence, Theresa May will be returned as PM.

Hence, Scotland requires a tranche of SNP MPs defending Scottish interests against the incumbent UK Tories.

Angus Robertson called the SNP "the real opposition"

In opening the event in Perth, the party's deputy leader Angus Robertson called the SNP "the real opposition".

Perhaps they might attach another soubriquet in future. The "strong and stable" opposition?

In particular, they would use this position to counter what they characterised as Conservative attempts to constrain benefits for the poor.

But would not power lie in Numbers 10 and 11 Downing Street, I asked?

Ms Sturgeon replied that Mrs May had already demonstrated a propensity for U-turns.

With a strong Scottish presence at Westminster, more such back-sliding could be expected.

Ms Sturgeon took this further.

A victory in Scotland for the SNP would guarantee that strong Scottish voice - and it would give "democratic legitimacy" to Ms Sturgeon's demand for a role in the Brexit negotiations. In effect, then, a mandate.

An intriguing formulation, that, given that Ms Sturgeon has previously argued that this election would not of itself count as a mandate for indyref2. She would explain the difference as follows.

Brexit is an issue for the whole UK. Her demand has been for the Scottish dimension to be heeded. Instead, it has been "brushed aside" by the PM. This election - the first available - therefore provides the mandate for her approach.

By contrast, she would argue that there is already a mandate for indyref2. From the Holyrood elections in 2016 and from a subsequent Scottish Parliamentary vote. These elections would "reinforce" that.

But what, I asked her, if the Tories say no?

What, in particular, if they adhere to their argument that indyref2 should not even be contemplated until Brexit is not just signed and sealed but is demonstrated to be working in practice?

That could be a much longer timescale than the one envisaged by the FM - which is when the terms of Brexit are known, the end of the negotiations.

That, she says, means Spring 2019 on the PM's timetable - but could slip back a bit.

Selling the jerseys

What, I asked again, if you get a No from the governing Conservatives - who hold sway because the constitution is reserved?

That, said Ms Sturgeon, would be "outrageous".

And Labour?

What if Ms Sturgeon is wrong and there is a Labour victory?

Mr Corbyn has said again that he might be willing to talk with the Scottish government about that demand for indyref2.

Aha, say the Tories, Labour is selling the jerseys.

Not so, say Labour spokespersons in increasingly adamant fashion, each time Mr Corbyn appears to hint at open doors.

Labour, we are told, knows its mind on an independence referendum. It is agin it.

Here's the quote: "As our manifesto states, it is unwanted and unnecessary, and we will campaign tirelessly to ensure that Scotland remains part of the UK."

Mr Corbyn, we are told, would merely use any talks with the SNP to persuade them to shelve their core demand.

More on this, one suspects, in the final week.

Let's see who's smiling then.

- Published30 May 2017

- Published30 May 2017