Building a bridge to growth

- Published

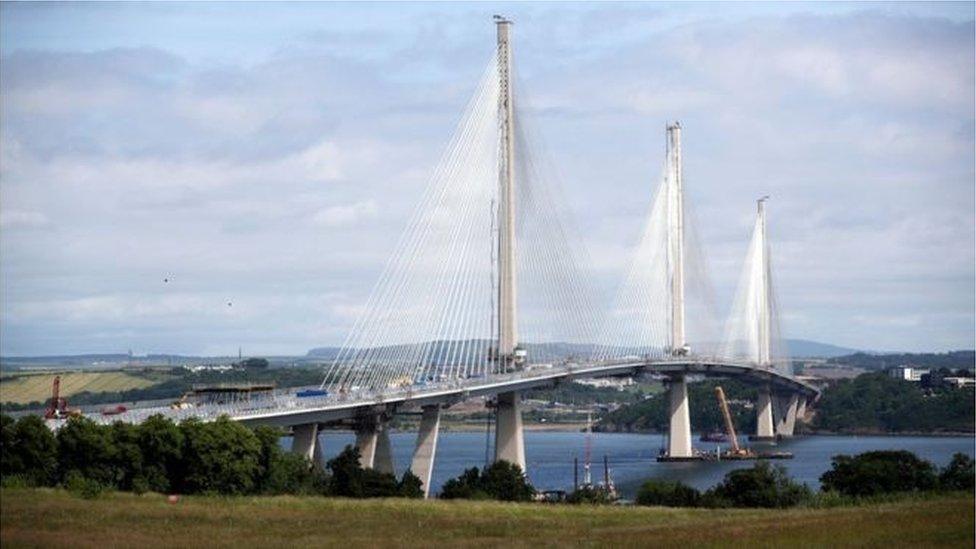

The Queensferry Crossing is opening on Wednesday

With some handy change from two billion quid, we've got ourselves a splendid new piece of architecture.

The Queensferry Crossing is the Firth of Forth's fifth, and its benefit goes well beyond the aesthetic, to be a vital link for the economy.

But how vital? A transport expert at Napier University, Professor Tom Rye, told my colleague David Henderson that the evidence of benefit from such big infrastructure projects is not clear.

For instance, he pointed out that Spain has more high-speed rail than any other European country, but it also has very high unemployment.

Now, I'm no transport expert or a professor, but that seems an odd illustration of his argument. Spanish unemployment might be linked with quite a lot of other factors.

Where he may have more of a point is the suggestion that pouring one's capital budget down the cable casing of nationwide high-speed broadband could be a more important way of connecting up the modern economy than pouring it into the concrete mix for more conventional road and rail.

That's Fife

What marks out the Queensferry Crossing as an unusual bit of real estate is that it's not expanding transport capacity - not by much, anyway. It's a replacement.

The Scottish government chose to maintain the same road space as the Forth Road Bridge (the 1964 one), which was based on future traffic growth that fell well short of reality.

This was part of Holyrood's cross-party commitment to constraining traffic growth, for environmental reasons. The only relief of pressure from the existing bottleneck is that the older road crossing will be available for buses and hardy cyclists.

In 50 years from now, that might look a bit silly. By then, if there's any common sense left in public policy, road use will be priced by which miles are travelled and at what times, rather than the blunt instrument of fuel and vehicle duty.

Rather than keep a bottleneck at the same width until perhaps the 22nd Century, pricing could take the strain of delivering on environmental goals.

Either way, road use will surely also have changed, through autonomous vehicles making more efficient use of space, and electric cars cutting down on emissions.

Corroding cables

So anyway, what are the economic claims made for the Queensferry Crossing?

Ten years ago, the report which led to the current bridge being commissioned estimated the bridge would cost £1.4bn at 2002 prices (makes you wonder if the original budget was high-balled, when the pain of the Holyrood building fiasco was still raw).

It then went on to count up the financial benefits. Those benefits depend heavily on the prospect of massive disruption from the older, corroding road crossing being closed or constrained by a decade or so of repairs.

Transport Scotland reckoned that cable replacement, with the old bridge still in use, would cost up to £1.3bn, and the permanent loss of 3,200 jobs.

Add up the other benefits of a sparkly new bridge, and you reach somewhere just north of £6bn.

So 10 years ago, it was reckoned that for every pound spent on it, you could expect £4.31 back. That seems quite a good investment.

Tunnel vision

This wasn't the only option for a new crossing. A look in the rear view mirror shows that three tunnel options were assessed, and a repeat of the Forth Road Bridge design.

The most attractive such underwater option was about a mile east of the current bridge, between Inverkeithing Bay and Dalmeny headland.

That would have required twin, five-mile bores through old mine workings and uncertain geology.

It would, it was reckoned, have delivered more benefit - some £6.3bn, but it would have cost about £2.2bn. Hence, a significantly lower ratio: for £1 cost, benefit of £2.91.

So what's next? Well, both the Scottish and UK governments would probably reassure you that they're on the case with roll-out of broadband - though not far or fast enough for some.

Public transport campaigners want to see the balance of spend shift to rail, arguing that the Edinburgh-Perth services are running more slowly than they were 100 years ago, "due to under-investment".

Making tracks

It is the Edinburgh-Glasgow rail corridor that is getting the big rail spend for now, to electrify it and cut 10 minutes off the journey from Queen Street to Waverley.

Perhaps by no coincidence, the outline business case for Edinburgh's tram extension was published on the same day the Queensferry Crossing was being handed over by contractors.

Ten years ago, the trams were the project SNP ministers wanted to stop, but in a Holyrood minority, they were outvoted.

It went way over budget. An inquiry is trying to find out why.

The Edinburgh Tram project went way over budget

But the logic of extending it is quite strong. The case sets out a cost of stretching the tram from the New Town to Leith would be £165m, taking three years for construction, and with a benefit of £1.64 for each £1 spent.

Yet another central belt project, goes the cry from the hills.

Fair point, except that the parts of the economy that benefit most from relieving the pressure on the older Forth Road Bridge are the ones to the north. If it had closed, those job losses would almost certainly have been far worse in Fife, Tayside and into the north-east.

Look at it another way: the key blockages for getting Scottish goods to key European export markets are not in Scotland, but around Birmingham and London. Spending in the south can make a big difference to the north.

Take the high road

The big northerly projects that are being prioritised are the A9, being dualled in stages between Perth and Inverness by 2025, and the A96 between the Highland capital and Aberdeen.

And if you - or Professor Rye - want to see where infrastructure spending has a tangible benefit, look at Inverness.

Before its completion in 1983 - with the Kessock Bridge across the Beauly Firth opened the previous year - the A9 was a tortuous travel nightmare, winding through small towns and twisting under narrow rail bridges.

It was one of the reasons in the 1960s that Inverness lost out to Stirling in the competition to attract a new university campus.

Now, drive north across the crossings of the Cromarty and Dornoch Firth, and you can see, in communities through the spine of Scotland and the far north, that a good road is a vital piece of infrastructure.

Its benefits can't always be measured by accountants in Net Present Value. The open road brings jobs, incomers, tourists, social change and confidence. A congested road can choke that off.

More ingenuity

All this goes some way to responding to the challenge of picking up the pace of growth - a challenge underlined last week by the report on 2016-17 Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS).

Infrastructure helps the economy move more smoothly. It gets goods to customers, and workers to work.

Broadband does both of those too, letting workers operate away from base, and helping the digital economy spread.

A further, crucial part of the growth story is the quality of those workers and of what they produce.

Government is a big spender on education and skills.

But also being discussed on Good Morning Scotland today was a parallel question about investment - is it spending on the right priorities, and matching skills to market demands, when so many in Generation Y, the millennials, are in roles which don't use those hard-won skills?

Building a bridge between Fife and Lothian is an impressive achievement. Building a bridge to the educational demands of the future economy and society requires even more ingenuity.

- Published30 August 2017

- Published29 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017