Programme for government: Education remains number one priority

- Published

A new education bill was announced as part of this year's programme for government

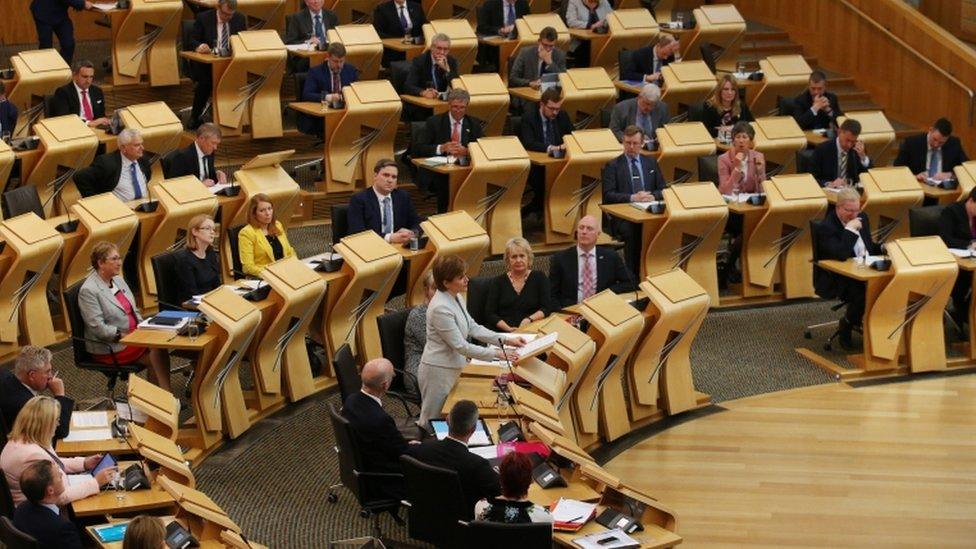

As Nicola Sturgeon outlines her legislative programme for the next year, BBC Scotland's education correspondent Jamie McIvor assesses the challenges facing the government on education.

The Scottish government wants to be judged on its record on education so it was fitting that it was the first big theme to be addressed by the first minister when she delivered her programme for government.

Improving early learning, raising attainment in schools and helping more youngsters from disadvantaged backgrounds get to university are familiar themes for the first minister.

Education, Ms Sturgeon claims, is the government's number one priority.

She promised more support for the expansion of nursery education but the single biggest issue in the coming months will probably be the reform of school governance.

Ms Sturgeon said a new education bill would deliver the biggest and most radical change to how schools are run since devolution.

Head teachers, she told parliament, would receive significant new powers, influence and responsibilities, formally establishing them as leaders of learning and teaching.

She said the reforms would be matched by resources.

The broad aims of the reform of school governance are clear: more formal powers for head teachers and a greater degree of parental involvement.

What is not clear for now is exactly what this will mean in practice.

Head teachers are to receive significant new powers

Some head teachers wonder if they will simply end up with official responsibility for things they already deal with through devolved local management structures. Others, despite government reassurances, fear more bureaucratic or administrative responsibilities.

Another question is precisely what role parents or parent councils will actually have.

Lastly there is the question over the exact responsibilities councils retain and what may be done by planned new regional education boards or "regional improvement collaborative" as Ms Sturgeon called them.

It is, however, clear what the governance changes will not lead to. Schools will not be able to leave local authority control completely and there will be no grammar schools.

However the government makes it clear changes to governance are not an end in itself.

Ultimately the aim is to empower head teachers to do what they think is best to raise attainment - standardised assessments now being introduced should make it easier to see which schools are making progress but, as Ms Sturgeon told parliament, they will not improve attainment in themselves.

Ms Sturgeon said education was her government's number one priority

A degree of direct government funding for schools - targeted at disadvantaged areas and based on the numbers of pupils eligible for free meals - is designed to complement normal local authority funding and help heads raise attainment.

But the government will have a lot to do to satisfy opponents - after 10 years in office, inevitably, there is a sense that sceptics can no longer give the government the benefit of the doubt while opponents sense that education is an area where the government can be held to account.

There is no sign of progress on improving literacy and numeracy - indeed in certain areas standards have declined. Scotland was classed as "average" in all three areas measured in the international PISA study last year - the country's poorest performance ever.

Although councils now have to broadly maintain teacher numbers, the total number of teachers employed in Scotland fell for several years. There is no overall national shortage of teachers but some councils face significant problems recruiting them - particularly in subjects such as science, technology and maths.

While the government aims to close the gap between how well youngsters from relatively rich and poor backgrounds do and raise the number of disadvantaged youngsters who get to university, some would point out that there are few, if any, mainstream politicians in modern times who would have disagreed with this broad notion. The question that could be asked of any politician declaring such intent is whether their policies are genuinely helping or whether the reality is living up to the rhetoric or good intent.

Nicola Sturgeon is not the first politician to say they wanted to be judged on education. Tony Blair famously said in 1997 that his priorities were "education, education, education".

She will be under pressure from the profession and opponents to ensure her aspirations achieve results. But, realistically, any significant improvements will take years to become evident and time is not always on the side of politicians.

- Published5 September 2017

- Published5 September 2017