Scottish devolution: Believing in impossible things

- Published

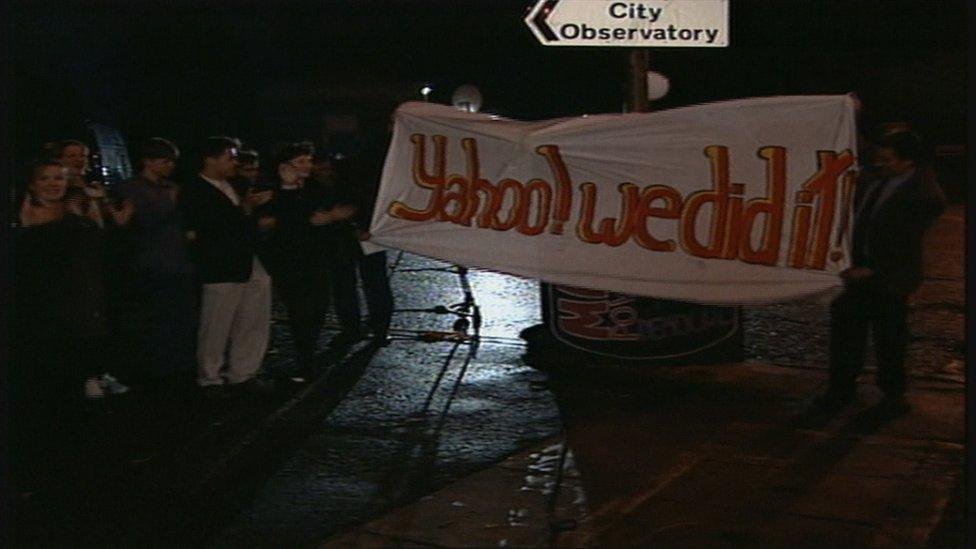

Scottish devolution vote from the archive

It is not necessary to adopt in its entirety the practice followed by Lewis Carroll's Queen. That is, to believe six impossible things before breakfast.

But still, at various points, a degree of uncertainty, even implausibility, has attached itself to the Scottish self-government project.

Would it ever happen?

Was the referendum a mistake, even a betrayal?

Would the people of Scotland go for it?

Would they back tax powers in particular?

Would That Bloody Building ever be finished?

Lest you have forgotten, the answers, in order, are: Yes; No/No; Yes; Yes; and Yes.

It is mildly amusing, glancing back over the past 20 years, to contemplate how many things currently regarded as fixtures were previously seen as unlikely, even impossible.

Heated debate

Sometimes, perspective can slip a little. For example, I have seen it suggested that the SNP were opposed to the present parliament at its outset.

That is not accurate. I recall the SNP gathering in Perth at which the party's stance on this matter was determined, prior to the referendum which we are commemorating today.

I recall the lively, even heated debate.

I recall the former leader Gordon Wilson arguing that devolution was a blind alley, a con.

I recall his successor, Alex Salmond, arguing very firmly to the contrary, that the party must endorse and campaign for a Yes/Yes vote in the referendum.

The SNP backed Alex Salmond's stance on devolution

I recall Mr Salmond's view: that the devolved parliament on offer was a palpable improvement in Scottish representation and that, further, the people of Scotland would neither understand nor forgive an SNP which took a different approach.

I also recall the vote which, overwhelmingly, backed Mr Salmond's approach. The SNP duly campaigned vigorously for a parliamentary package they had played no direct role in framing because they had withdrawn from the cross-party Constitutional Convention.

So the SNP were quite definitely in the Yes/Yes camp in 1997. Albeit they wanted - and want - more. Albeit they initially expressed doubts as to Labour's ability to deliver devolution. Remember the pizza gag?

Prior to the referendum itself, devolution frequently seemed unlikely. The Conservatives were resolutely opposed - and tended to form the UK government more frequently than their rivals.

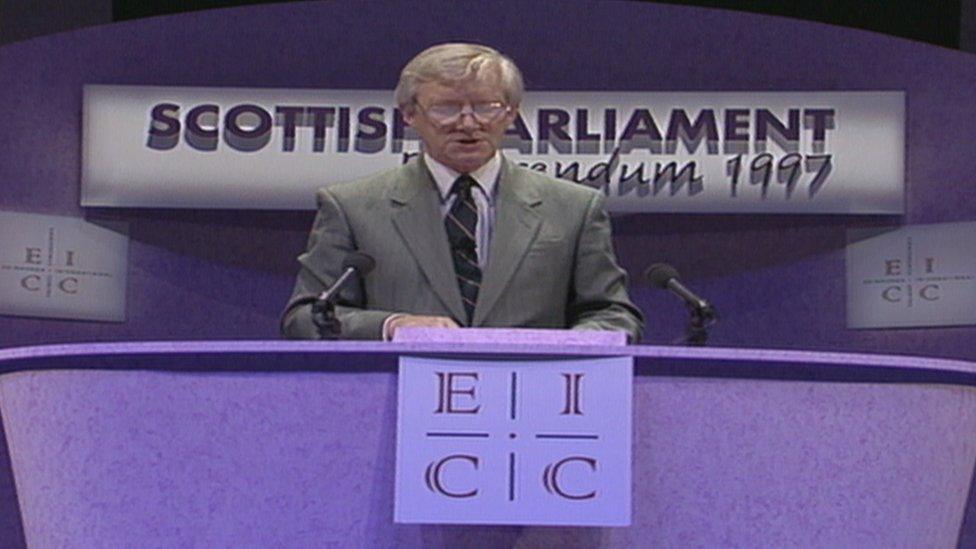

Voters backed a new parliament with tax varying powers in the 1997 referendum

They were also, incidentally, completely agin PR voting.

It is a source of innocent merriment to record that the Scottish Tories were rescued from near-oblivion by a combination of… devolution and Holyrood PR.

To be fair, the Tories also find that decidedly entertaining. In retrospect.

But Labour vacillated on devolution. Some were firm adherents. Some were pragmatists: if we must, we must, but don't expect me to smile.

Minimal resources

Some were against. They divided into two broad camps - staunch Labour types who regarded it as an unwarranted sop to Nationalists which might dilute the party's own clout, and Labour internationalists who mistrusted the concept of Socialism in one country.

Importantly, the various elements of opposition to Scottish self-government, sincerely held and firmly advanced, have all tended to retreat.

Donald Findlay, for example, led the No camp with vigour if, as he notes himself, with minimal resources. He remains notably unimpressed by Holyrood and its work - but observes that abolition now is a "nonsensical argument".

Twenty years ago, the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party took no formal, active stance with regard to the referendum. Individual Tories remained opposed - but the party could discern the direction of the wind.

They had already received a fairly clear barometric hint from losing every Scottish Westminster seat in the 1997 General Election.

So it was left to Mr Findlay and others such as Brian Monteith to press the case for No.

And the Yes campaign? As billed, it was an intriguing blend of Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the SNP and sundry non-partisan adherents.

The project was very closely associated with the person of Donald Dewar: one of the genuine Labour devolutionists identified earlier.

It had fallen to George Robertson, as shadow Scottish secretary, to withstand the quite remarkable turmoil which attended the announcement of the referendum in 1996.

Few certainties

There was talk of betrayal. Talk of a clique running policy. Talk of strategy driven by the leadership, by Tony Blair.

In short, the familiar story of everyday life in the People's Party.

For a spell, though, this was a remarkably vitriolic row, reflecting my essential point that there have been precious few certainties and no absence of upset in the history of devolution.

Indeed, a wise observer once noted that devolution resembled evolution. It just took longer.

Tony Blair believed a British football league would help bind the UK together

In an interview with me, Tony Blair says he always found it passing strange that he was accused of betraying the Scottish people - when he was proposing to consult them directly, to empower them.

Mr Blair, of course, understands only too well that the underlying concern was that the two question referendum was designed to dilute devolution, especially on tax, and perhaps even to thwart it entirely.

The former prime minister tells me he went back to the history books. He perceived that every attempt at Scottish devolution - and there had been many - had foundered on entrenched opposition at Westminster, particularly in the Lords.

It was important, he concluded, to pre-empt that by securing a clear popular mandate.

And tax? There had been distinct contention surrounding that question - Michael Forsyth had run an effective campaign against the "Tartan Tax".

Team Blair concluded it would be right to garner a specific endorsement for that, again in advance of Westminster proceedings. It was about implementing devolution, not blocking it.

That argument turned out to be justified - as did his assertion in the interview with me that the topic had to be tackled early in his premiership. The devolution bill went fairly smoothly through parliament.

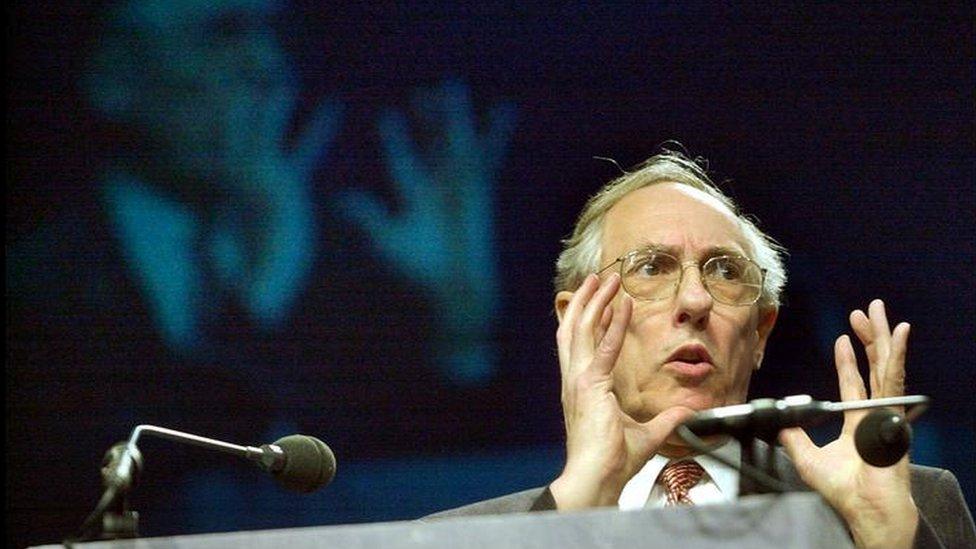

Donald Dewar regularly envisaged the worst

But back to D. Dewar. As noted, George Robertson had borne the slings and arrows of the referendum process argument. But Donald Dewar had been the devolution champion prior to that - and he was given the job again in government.

He then faced doubts. Not his own, at this point, but those expressed by Cabinet colleagues. After years of Convention debate, Mr Dewar and Scottish Labour tended to regard the essentials of devolution as given, as fundamental.

Mr Dewar's Cabinet chums, perhaps understandably, did not pursue the same line. They wanted to go back to basics. They needed to be convinced all over again.

Mr Dewar had a tough time in DSWR, the Cabinet committee convened to consider devolution to Scotland, Wales and the Regions.

Pragmatic gloom

The matter was only truly resolved when Tony Blair intervened to offer Mr Dewar direct, potent support in return for a few prime ministerial red lines such as the continuing sovereignty of Westminster.

But, in the referendum itself, was Donald Dewar a model of unvarnished certainty at all times? Did he believe that all would ultimately be for the best in the best of all possible worlds? Those who knew him will smile gently at the suggestion.

To the contrary, he was the epitome of structured, pragmatic gloom. He regularly envisaged the worst which could happen, thus preparing himself and his team for the strategies which might be needed.

At various points, he convinced himself that the people of Scotland would vote No to self-government. Or deliver an uncertain Yes, as in 1979.

Or they would undoubtedly reject the tax powers (plus or minus 3%, on the standard rate). It was counter-intuitive, he told me in his best downbeat voice, to expect people to vote for potentially higher tax. The second question on tax? Not a chance.

In the end, the result for Mr Dewar was "very satisfactory", to use the phrase exchanged between D. Dewar and T. Blair after the PM's helicopter touched down on the grass outside Holyrood, palace and parliament, the day after the referendum.

Nothing stands still

But uncertainty remained. The early days of devolution were troubled. Not least because of the controversy over the cost of the new Holyrood building. Folk were understandably angry - and turned that ire upon the entire devolution project.

Then the biggest variable of them all. The churn which is the core of electoral politics.

Alex Salmond puts it rather well in a phrase he is fond of repeating. In my view, it bears repetition for the wider lesson it projects.

Mr Salmond recalls he was regularly told there would never be a Scottish Parliament. Then he was told the SNP would never win power. Then that they would never secure a Holyrood majority. All three happened.

The wider lesson?

That nothing stands still.

That change is rooted in democracy.

That sometimes the only thing puzzling about "six impossible things before breakfast" is: so few? So late?

- Published7 September 2017