Setting boundaries: Drawing up Scotland's new electoral map

- Published

The Boundary Commission for Scotland have drawn up maps - lots and lots of maps

The latest set of proposals for Scotland's new electoral map have gone out for consultation, amid calls for the government to scrap the review altogether. How did we get to the current plans, and what might they mean for Scotland's MPs?

What's the big idea?

Under current electoral law, boundary reviews have to be carried out periodically to keep up with demographic changes - for example, so that fast-growing urban areas have enough representation.

The government would also like to cut the number of MPs from 650 to 600 - saving the taxpayer money in paying for them, but leaving each MP with more constituents to represent and thus more work to do.

There have been various claims of political gerrymandering around the proposed changes, with speculation about which party might benefit, but the review itself is carried out by a non-partisan Boundary Commission for each of the UK's constituent countries.

North of the border, the job falls to the Boundary Commission for Scotland.

This group is headed up by Lord Matthews, a High Court and Court of Session judge, alongside two commissioners - Ailsa Henderson and Paula Sharp - and a secretary, civil servant Isabel Drummond-Murray.

They drew up an initial set of proposals in October 2016, and have now set about fine-tuning them in response to comments from the public.

How are these changes decided?

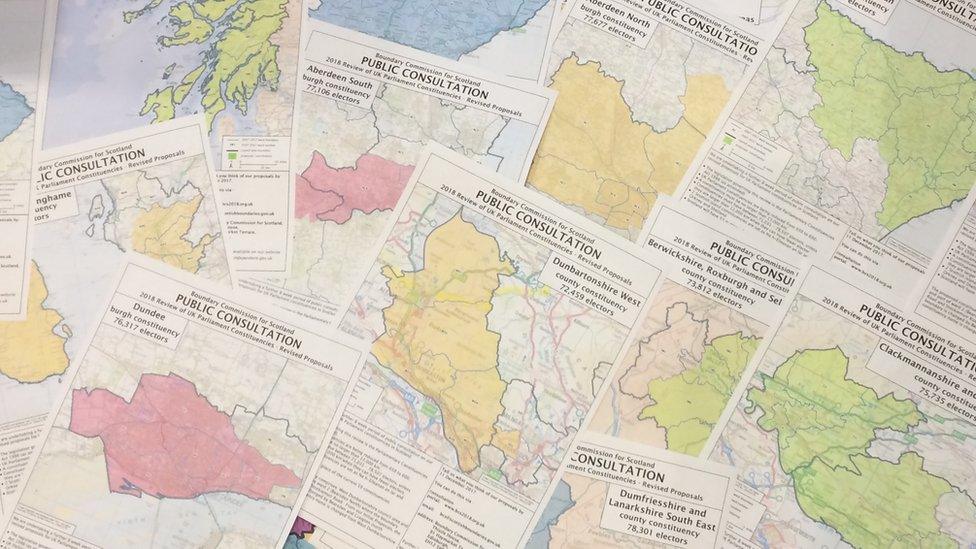

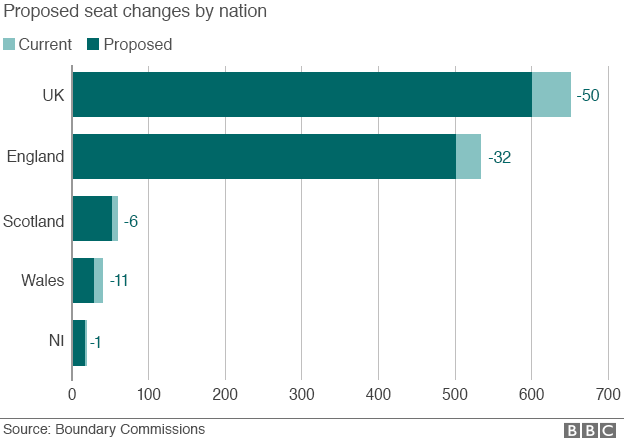

Each part of the UK is looking at losing some MPs under the plans

The maps drawn up for new constituencies are based on three key criteria:

First, that there should be 53 Scottish seats - six fewer than at present - to satisfy the cut to 600 total seats

Second, no constituency should exceed 13,000 square kilometres (5,019 square miles)

Third, each constituency must have between 71,031 and 78,507 voters - with some leeway for large, sparsely-populated areas

The latter two rules are set out in legislation, which leaves only a narrow window for changes in some cases. In addition, the island constituencies of Orkney and Shetland and Na h-Eileanan an Iar are protected under law, which leaves two less to be tinkered with.

The Commission team said they were unable to amend their initial plans for some seats - like the new ones in the Highlands area - because they had to satisfy both the population and size requirements, and the constituencies can only stretch in so many directions.

The current plans for the new Highland North seat have it sitting at 12,985 sq km, barely squeaking in under the limit. There is almost literally no room for manoeuvre.

Lord Matthews said: "Where the legislation has allowed it, we have tried to respond to the views expressed to us. However in some areas we have been unable to make changes because of the constraints on constituency design within which we work."

Where might the biggest changes be seen?

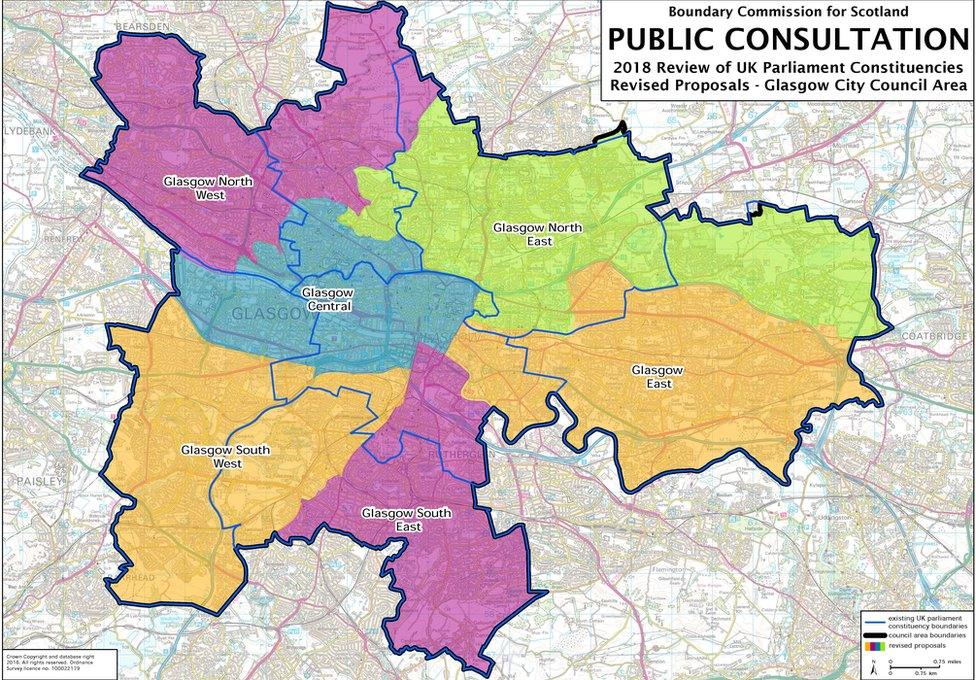

Glasgow would go from seven seats to six under the plans - with changes across the board

Unless you live in one of the island seats protected under law, the chances are you might see some changes, at least in name.

The only seat which will remain untouched from the 2005 election will be East Lothian, which follows the boundaries of the local council.

The impact of the changes is really spread across the country as a whole, but is most noticeable in a few standout examples.

Under the plans, Glasgow would encapsulate six seats, rather than the current seven. This is not a case of a particular Glasgow seat disappearing, and MP X disappearing as a result; as the map above shows, the changes would be widespread.

There are also some fairly labyrinthine changes in the north east of the country, with Gordon mostly being merged into the old Aberdeenshire West and Kincardine seat and part of Banff and Buchan, while Angus grows into Kincardine and Angus North - which itself loses some territory to Angus South and Dundee East, which eats up the northern part of what used to be two Dundee seats.

Yes, it's complicated - and far-reaching. This is why, rather than being able to pinpoint a particular MP being out of a job as a result of the changes, in most places a wider bun-fight will develop over nominations for the next election.

Neighbourhood disputes

The changes might leave some MPs competing with colleagues over a single seat - like Ian Blackford and Drew Hendry

If the changes go through, come the next election each party will suddenly need one less candidate from Glasgow. This could mean some sitting MPs might find themselves up against current colleagues just to make it onto a ballot paper.

And because almost every constituency is taking over territory from their old neighbours, incumbents might hope to pick and choose which of the new options gives them the best hope of re-election.

Another good example of this is in the Highlands, where three large constituencies could turn into two even larger seats (with the addition of the neighbouring Moray seat expanding somewhat and various other bits of territory changing hands - again, it's all rather complicated).

This could pit the SNP's Westminster group leader Ian Blackford (Ross, Skye and Lochaber) against his colleague Drew Hendry (Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey) for the right to be the party's candidate for Highland South.

To the east, a swathe of four seats gained by the Conservatives in the most recent election could, at the next vote, only make up three constituencies. Banff and Buchan, Gordon, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine and Angus are merging together into three larger seats - Kincardine and Angus North, Gordon and Deeside and an expanded Banff and Buchan.

This will leave four newly elected Scottish Tories - Andrew Bowie, Kirstene Hair, Colin Clark and David Duguid - competing for just three candidacies. In the political game of musical chairs, one seat has been removed.

Changes could leave North East Tories competing for candidacies (current boundaries in red lines, new ones coloured)

Just next door to the south, SNP representative Stewart Hosie could see his Dundee East seat - once the safest in Scotland - lose most of its city wards as it is swallowed up in the new Angus South and Dundee East constituency.

The SNP has done well in the city in recent years, but lost Angus to the Conservatives in June. Might Mr Hosie be tempted to challenge colleague Chris Law (currently MP for Dundee West) for the new Dundee seat instead?

Such quandaries are common. Questions also abound for Labour's Ian Murray, whose stronghold of Edinburgh South - the current safest seat in Scotland - would be torn neatly in two, as the seat shifts westward and becomes Edinburgh Southside.

In any case, the boundary commissioners stress that they "never look at the electoral impact" of the changes, given their non-partisan standing. "We can't, and we don't."

How much has changed since last October?

Banchory, on the banks of the River Dee, was briefly to be removed from the Deeside constituency

Some 2,000 responses were sent in to the consultation on the initial proposals, in formats varying from emails to letters to Christmas cards. Many of the changes called for have been reflected in the latest draft.

Some of the changes are small - seven of the constituencies are simply having their names changed from those initially proposed - while others are more significant. But in the tricky world of boundary-balancing, even tiny changes can have big impacts.

Banchory, a town in Aberdeenshire, was initially placed in Kincardine and Angus North. Following more than 200 complaints from residents who could see the River Dee out of their window but were for some reason not in Deeside, the commissioners moved it back - but this led to "fairly large knock-on effects" in terms of population sizes, necessitating further changes elsewhere.

Changes were also called for in Fife and Perthshire, where plans to overlap parts of these communities apparently "were not liked by local residents" - with the 100-odd negative responses "predominantly" from those on the Perthshire side. Did they just not fancy being Fifers?

Anyway, are all of these changes a sign that the commission got it wrong with the initial proposals? They say no - this is merely fine-tuning, and in many ways a good thing, with public opinion being taken into account.

Ms Henderson, who is also a professor at Edinburgh University, said: "It's not that we got it wrong last time - it's that we're trying respond to public consultation and stay within the rules."

What's in a name?

Simpler names - trickier selection battles

There has been much debate over the names of proposed new constituencies.

As seats have expanded to take in different areas, commissioners over the years have been keen to reflect the communities covered. But this can resulted in unwieldy names, such as the aforementioned Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey, which some baffled voters have complained about.

Hence, the new proposals see East Kilbride, Strathaven and Lesmahagow become simply Lanarkshire South West. Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Monklands East becomes Lanarkshire North.

Those seats in the north of the country which previously name-checked more or less every large settlement nearby have become Highlands North and Highlands South. All much simpler, the thinking goes - although it does mean that for the first time, there might be no constituency naming Inverness.

In one of the quirkier changes, the commission also propose turning Dumfries and Galloway into...Galloway and Dumfries.

Is it actually going to happen?

Arlene Foster's DUP might put paid to Mrs May's boundary review, opposition politicians have speculated

In the end, all of the Boundary Commission's work may be for nothing, as speculation has emerged that Prime Minister Theresa May is set to bin the review altogether.

The Times newspaper quoted "three senior sources" in a story in September, external revealing that the plans - which were included in the Conservative manifesto for June's snap election - are "likely to be scrapped" due to backbench opposition.

With speculation that the DUP might not back Mrs May's government over a review, there may be no chance of a parliamentary majority in favour of them - MPs even voted in opposition to cutting their numbers in 2016.

Such a move has been backed by some opposition parties, who have called for the proposals to be binned; the SNP say that "fiddling with the boundaries of MPs' constituencies is the last thing the UK government should be wasting its time on" at present.

The commissioners say they are not listening to the speculation - they just have to keep their heads down and keep working on the proposals until they are told otherwise.

But it is hard to imagine they would not privately be somewhat frustrated if the detailed, meticulous work they have put in poring over maps and spreadsheets all turns out out to be for nought.

- Published17 October 2017

- Published20 October 2016

- Published18 October 2016

- Published13 September 2016