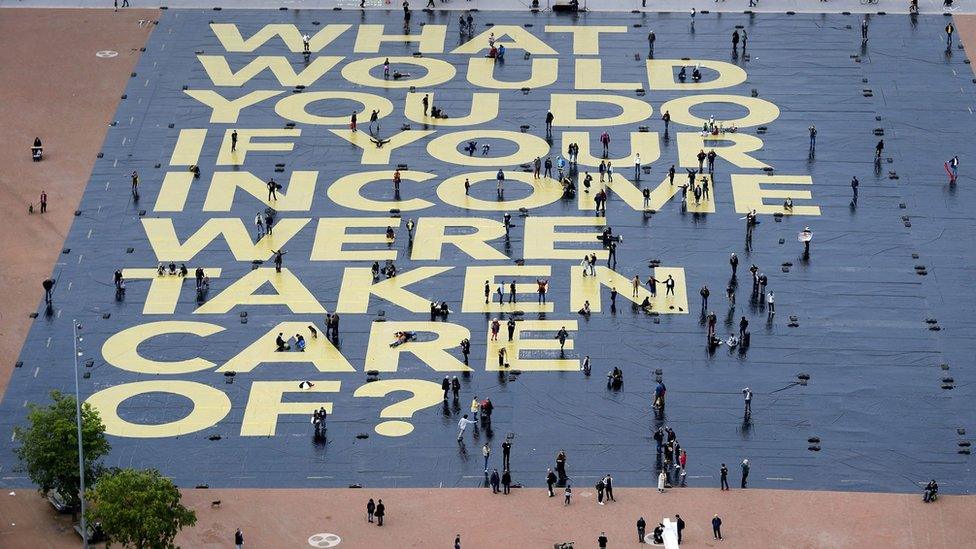

Citizen's income: Could it work in Scotland?

- Published

The Scottish government's draft budget for the coming year includes funds to study the idea of setting up a "citizen's income". So what is a basic income system, and how might it work in Scotland?

What is a basic income system?

The basic income system is a radical redesign of tax and welfare - completely redrawing the relationship between the state and the citizen.

Under such a system, every individual would be given a cash payment at regular intervals, without any requirement to work or demonstrate a willingness to work. Several different figures have been suggested, mostly in the rough area of £100 a week for adults.

As the name suggests, it would be universal - paid out to every citizen regardless of their wealth, employment or personal status - and would be enough to cover the basics of life. It would serve as a replacement for existing benefits payments such as jobseeker's allowance.

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), a charity which has undertaken extensive studies, external about basic income, call it "a basic platform on which people can build their lives - whether they want to earn, learn, care or set up a business".

Enthusiasm about the possibilities of a basic income has sprung up in several countries in recent years, but it is by no means a new idea. References to such a scheme date back as far as 1516,, external and have been debated by political theorists and philosophers ever since.

What could the benefits be?

Proponents say a basic income system would cut out a lot of bureaucracy in the welfare system

The money distributed in a citizen's income system is given out with no strings attached, so the idea is that it affords the individual freedom of choice.

Beyond the basics of food and shelter, people can put the money towards education or training, or launch entrepreneurial enterprises or creative endeavours.

A guaranteed safety net could see more people take a punt on starting a business or volunteering in their community - or they could devote more time to caring for relatives or friends, something which may become more and more necessary with an aging population.

Giving everyone money unconditionally also cuts out a huge amount of bureaucracy in the welfare system. No forms have to be filled in, no appointments kept at the jobcentre, no eligibility interviews held or home visits conducted.

While there would be great cost and upheaval in setting up such a system, once established it would be relatively cheap and simple to run - in stark contrast to the current system.

It could also cut out some loopholes in the current system which can disincentivise work. Because the payments would be guaranteed, jobless people would be able to take on limited or seasonal work without facing having their benefits cut off.

Proponents also point to the looming issue of automation. If a significant number of workers are made redundant by machines, something like a basic income might become necessary as people go through retraining for different fields or find their new role in life.

What could the downsides be?

Many of the complaints about basic income schemes are founded on cost

Opponents of basic income schemes baulk at the idea of paying people to do nothing; they fear it would be ruinously expensive and foster a generation of unmotivated couch potatoes.

As noted above, backers hope that a basic income would make all work pay and encourage more people into work - but there are concerns it might have the opposite effect.

The SAK trade union in Finland, where a pilot programme of basic income is currently being run, argue that the system might reduce the labour force, external by tempting new parents or those close to retirement to cut their hours.

They also call the model being trialled "impossibly expensive", a criticism repeated by most opponents of the basic income.

One Welsh economist voiced fears of a "tremendous tax" as a result of the "extremely expensive socialist experiment", suggesting that it would be a disincentive to work both for low earners and those on higher incomes who would effectively pay for the system via their taxes.

On that latter point, concerns have been raised about social cohesion in a basic income society; at present the welfare state is justified on the grounds of people receiving redistributive payments on the basis of need, but would the taxpayer be as happy to fund a system where people could avoid contributing by choice?

There are also questions over what this would mean for immigration and open borders. Say Scotland had a basic income system and England did not - would the jobless of Carlisle or even the continent flock north in search of a payday?

The whole point of the basic income is that it is universal, so restricting it only to locals would run the risk of creating second-class citizenries - but leaving it open to all comers might not be practically possible.

Another more political complaint is that the state would play a very central role in any country with a basic income system, involved closely in the life (and bank balance) of every citizen.

And as for the job-stealing robots, detractors point out that concerns about technology are nothing new. The labour market has always evolved, with the workforce moving from the farm to the factory to the office - machines might yet prove the equal of humankind, but not yet.

What are councils doing?

Four Scottish councils - including Glasgow - are looking at holding pilot programmes

The Scottish government has set aside £100,000 in the draft budget to help fund basic income pilots at local authority level.

Four councils have been linked to potential pilot programmes - in Glasgow, Fife, North Ayrshire and Edinburgh.

Even the most advanced of these are at a very early stage - mostly currently focused on feasibility studies of how a pilot could be carried out, rather than how a system could be rolled out across a council area or the country as a whole.

In general, the pilot schemes would be limited to a specific area, with unconditional payments sent out to individuals for a period of about two years. However, the start of the pilots are still some time off.

North Ayrshire Council, for example, set aside £200,000 in this year's budget to examine a basic income - but it is expected to take 12 to 18 months just to design a pilot scheme.

Equally, work at Fife Council, external is "recognised as a long-term project", with initial work "focussed on desk research and engagement with interested groups", and that in Glasgow, external is "at the very early stages".

Fife councillor David Alexander noted: "We must be realistic, this is a very complex issue which will take years of investigation and groundwork.

"It's far too early to say where a pilot might happen - we don't even know if it will be the right thing to try. But it could be a game changer, so we're taking it seriously, because we know we have to try new things and learn as we go."

And even once they get up and running, the pilots would have to run for several years before they could be evaluated - so any decisions about the wider future of basic income in Scotland is a long way off yet.

In fact, it may well be for a future Scottish government, after the next election in 2021, to look at the matter in earnest.

Could this really happen in Scotland?

Does Holyrood have the powers to set up a basic income system

For all the trials in what is proving a rather long pipeline, is there a realistic possibility of Scotland actually adopting a universal basic income system?

To get down to brass tacks, how much would it cost? Reform Scotland crunched the numbers, external for a £100-a-week system, and reckoned it would cost just over £20bn a year in Scotland.

There's no getting away from it: that's a lot of money. But, by scrapping a raft of benefits which the citizen's income would replace, removing tax-free personal allowances and hiking all rates of income tax by 8%, they reckon £18bn could be raised.

All of that would still leave a £2bn shortfall, but Reform Scotland argue this is not insurmountable via other savings and the hope that more people would join the workforce.

It's not just about money, though - as with most other things in Scottish politics, there is a constitutional element.

Anthony Painter from the RSA told MSPs on Holyrood's social security committee that there was a "basic problem" for them - a lack of powers.

He said a citizen's income would be "a wholesale change to the system of social assistance and tax", a "holistic change" - and as such, "you need to have powers over the whole system in order to implement a full universal basic income".

Siobhan Mathers from Reform Scotland told the same committee that it was "really quite difficult to run the numbers" even with newly-devolved welfare powers, adding that "it is easier to do pilots than it would be to roll out a wholescale change".

The main problem for a Scottish system as it stands would be the interaction with the aspects of tax and welfare which remain reserved to Westminster, such as Universal Credit. Many of the benefits which would be replaced by a basic income are not under Holyrood's control.

Effectively, any Scottish basic income scheme would have to be set up either in partnership with the UK government, or with its blessing via the devolution of further powers.

Has this been tried elsewhere?

Experiments with basic income systems have been mooted in a range of different countries

As mentioned above, a two-year pilot programme is currently running in Finland, where 2,000 unemployed people are given a €560 (£490) monthly income, whether they wanted it or not.

This is the largest and most advanced trial currently running, at least in Europe, but results will not be published until 2019. Nicola Sturgeon has recently tweeted, external out links to studies of the Finnish experiment.

The government in Ontario, Canada is running a basic income project, external in three communities, focused on people on low incomes, although the payments vary, based on earned income.

Charities in the US have also set up projects giving unconditional cash transfers to villagers in Kenya, external and Uganda, external.

However, a proposal to introduce a similar system in Switzerland was comprehensively defeated in a referendum in 2016.

There is dispute over whether or not many of these pilots constitute a "true" universal basic income - for example the Finnish scheme focuses only on currently unemployed people, rather than society as a whole. Another pilot programme ongoing in Holland has been criticised as amounting only to a minimum guaranteed income.

To be a real test of a true UBI, a pilot programme would have to be mandatory, rather than voluntary, and include the already-wealthy too - something which may prove problematic, if the system penalises them through increased taxation.

All of this will have to be borne in mind as councils draw up their plans for pilots of their own.