And now, the Budget where you are

- Published

Business leaders and politicians are looking to economic forecasters to tell them what lies ahead

Weak growth is getting weaker, dragged down by weak productivity.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has given up on its sunny optimism of returning to Britain's past, modest growth in productivity (output per worker per hour worked).

We're not returning there for now, concede the Responsible Budgeteers. We're stuck somewhere closer to the dismal level of the past ten years.

Why? Maybe because of a lack of business investment. Perhaps it's the price to pay for allowing indebted companies to stay afloat when we should let them collapse.

It may be the price to be paid for having such exceptionally high employment levels - lots of people finding jobs, some of which are high quality and highly productive, but too many of which are neither.

Widgets

Productivity means those incremental improvements that mean we get better off. In theory, if your factory can make 2% more widgets per worker each year, then that ought to buy the worker 2% higher real earnings.

(That's on average, over time, across the economy, unless you take it in profit, lots of other things being equal etc - get used to it, this is economics.)

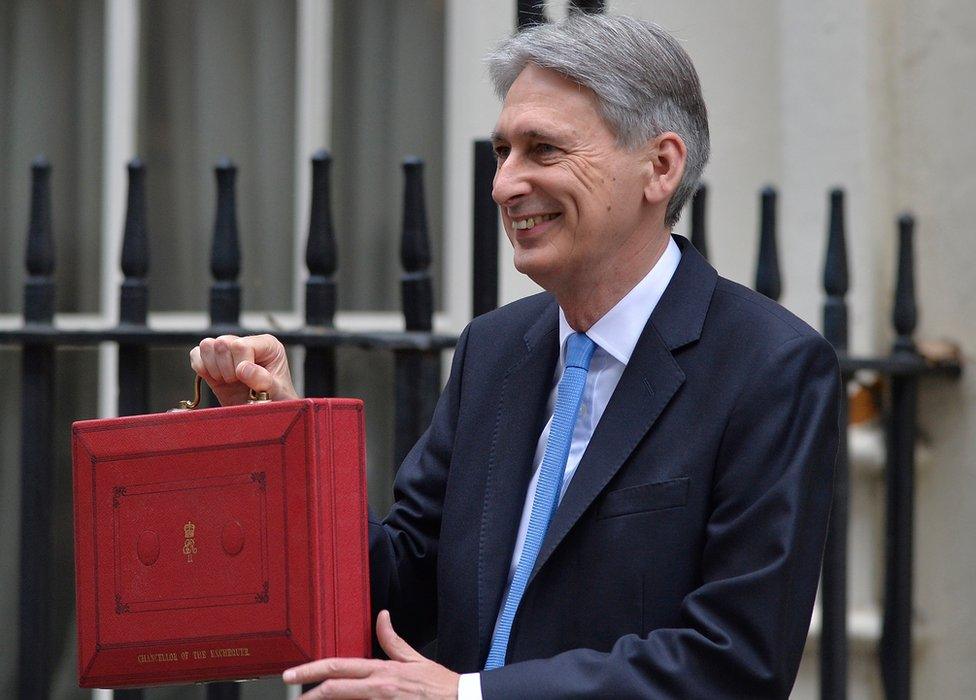

What's in the box? Philip Hammond prepares to deliver his Autumn Budget

So if that worker is making no more widgets per year - which is how UK Widgets plc has looked recently - there's no extra output with which to raise her or his pay. Not sustainably anyway.

So as productivity improvements falter, assume that economic output does too. Growth slows. And that's what the OBR is saying with its Budget report.

When growth slows, you don't get the buoyant increases in earnings, spending and profits which you might have otherwise assumed would slosh a lot more takings through to tax revenue. And that's where Philip Hammond reached in his second Budget of 2017 - hemmed in by low growth, borrowing targets, party politics and Brexit.

Independent forecast

But he's not alone. Scottish productivity, in 2015, at last caught up with the UK's low levels of productivity growth.

Its economic output growth in the past three years has been a long way below the trend growth for the UK. And now, it has very wide income tax powers. That's a combination that is going to hurt public services, unless growth rates and tax revenue rise.

And that's where the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) comes in. It's been around very few years, quietly assessing the Scottish government's accuracy in forecasting and delivering on tax revenues from Land and Buildings Transactions Tax.

Political artist Kaya Mar offered his own take on the chancellor's dilemmas

The Commission is chaired by Lady Susan Rice, august former chief executive of TSB Scotland. Its 20 staff are located in the refurbished former prison governor's residence, across a car park and over a wall from the civil servants and ministers in Edinburgh's St Andrew's House.

It recently took on new powers. It is now Scotland's version of the Office for Budget Responsibility. It provides the forecast for growth on which Derek Mackay has to base his budget. It draws on data from the Bank of England, Scottish business surveys, official data and newly published material from the OBR. That forecast lands on Mr Mackay's desk by next Thursday.

No wishful thinking

Using that as a guide, he then has a week to sort through his options for taxation and spending. Taxation, you'll recall, includes options on setting all income tax bands, thresholds and rates (other than the initial £11,850 threshold). Spending includes expensive new commitments on childcare, health and policing.

Mr Mackay delivers his plans back to the other side of the prison governor's wall by 5 December.

Lady Rice's team duly crunch the numbers on the policy choices through an economic model they've been working up.

And on Holyrood Budget Day - Thursday 14 December - we can see an independent assessment of what the economic and fiscal impact will be of the choices Scottish ministers are making. Not wishful thinking, or spin, but a robust assessment of what to expect.

Philip Hammond is in a minority government, which has a deal with Democratic Unionists to get the Budget passed.

Derek Mackay is also in a minority government. He has no such deal.

Unpacking the billions

Another thing: a wee note about £2bn. It's not a wee sum, but it might help to have some explanation.

It's the claim made by Philip Hammond for the additional money in his Budget coming to Scotland.

Sounds good. But what does it include?

For a start, it's spread over this year (a modest bit) and the next three financial years.

The source of controversy is that around £1.1bn is reckoned to be 'financial transactions'. That's a new-ish Treasury accounting device to distribute funds, on the understanding that they have to be repaid, eventually. They're for investments in realisable assets.

That includes funds going into government co-funding of strategically significant new industries. The Scottish Investment Bank could benefit.

It's also for student loans and for the Help-to-Buy scheme, aimed at supporting first time homebuyers by taking an equity stake, to be repaid when that first home is sold.

There's around £500m of the big number for conventional government capital spending, to build roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, courts and trams.

That's welcome, but not as much as being able to splash around the resource (aka revenue, or day-to-day spending) budget on public services, much of which goes into public sector pay. That comes to somewhere between £350m and £400m over the four years.

Efficiency

There's a spat between the governments about the amount allocated for the current financial year. There's rarely anything for the current year, but the sense of crisis in the NHS is such that £350m has been found for England's health service.

Scotland is allocated £33m as a consequence of the block grant formula. Yet Scottish ministers say it looks more like £8m.

I'm told that's what you reach when you include the cuts that are a consequence of an efficiency squeeze in other Whitehall departments.

It wasn't clear at last spring's Westminster Budget how much money that squeeze would release for Whitehall, so the devolved administrations in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Stormont didn't have that factored into 2017-18 grants. It's clearer now. So it's being factored in.

I hope that makes things clearer.

What's that you say? As November mud?

Perhaps Gladstone, the Treasury cat can make sense of it all?

- Published22 November 2017