Women 'probably halfway' to full equality

- Published

Suffragettes walked from Edinburgh to London to deliver a petition to the prime minister

A century on from women winning the right to vote, there are still many questions about how to achieve equal representation in politics.

Fewer than one in three MPs are women - and in the past few months there has been a sexual harassment scandal which many blamed on a macho culture in politics.

Prime Minister Theresa May is to lead a celebration marking 100 years since the Representation of the People Act, which allowed women over 30 to vote for the first time in the United Kingdom.

The fact that Mrs May is a female prime minister is an illustration of how much has changed in the past century.

But progress has only gone so far.

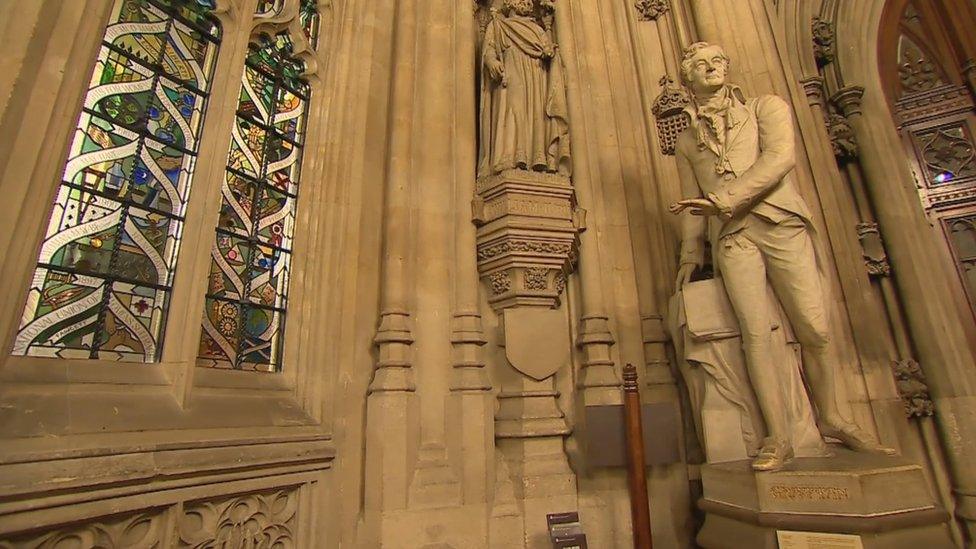

A statue of suffrage campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst stands near the Houses of Parliament

Theresa May is one of only two women among the 19 people to occupy 10 Downing Street since 1918 and women are still vastly outnumbered by men in the House of Commons.

At the end of 2017, two of Mrs May's cabinet had to leave high office amid the harassment scandal in politics.

So how much progress has been made in the last century - and how much more is needed?

At 27, Labour's Danielle Rowley would not have been allowed to vote even after the law was passed

Danielle Rowley is Labour's youngest MP.

At 27 years old, she would not have actually got the vote in 1918. It only extended the franchise to women over 30 who met certain property qualifications.

Ms Rowley is the first woman to represent the Midlothian seat.

"I feel incredibly grateful that through women struggling and fighting 100 years ago, I am here now, not only able to vote, but to actually sit in parliament and represent people," she says.

"I've had quite a positive experience as a young woman and I think that's quite a big change. I'm keen that change continues.

"It's never going to be mission accomplished until we see society completely reflected in parliament and in all walks of life. But we're getting there and we've certainly come leaps and strides in the past 100 years."

But, Ms Rowley adds, progress cannot be taken for granted.

"It's due to people fighting, it's due to passion, it's due to hard work," she says.

The parliament's souvenir shop sells votes for women mugs

Around the parliamentary estate, there are reminders of the fight for women's suffrage.

Reminders such as the chapel in Westminster Hall.

It is home to the small cupboard Emily Wilding Davison hid in on the night of the 1911 census so she would be recorded as resident in parliament that night.

She died a couple of years later after being struck by the King's horse at Epsom.

New Dawn symbolises the groups involved in the fight for the vote

Up the stairs, there's an artwork commemorating the suffrage campaign.

New Dawn consists of back-lit glass scrolls meant to symbolise the groups involved in the fight for the vote.

But if you go through the doors underneath New Dawn, towards Central Lobby, it does not take long to notice the statues share a certain characteristic.

The SNP's Kirsty Blackman says equality has probably hit the halfway mark

"Statues in parliament are overwhelmingly men, the pictures in parliament and paintings in parliament are overwhelmingly painted by men," says the SNP's Kirsty Blackman.

"It feels like a very patriarchal environment. It feels like a place where men are on top and it's supposed to stay that way."

On a scale of one to 10 - one being no rights, 10 being full equality -, she adds: "I think we're probably around the halfway mark.

Many of the statues in the parliament are male, says Kirsty Blackman

"I don't think we've got the stage where we're anywhere near actually equality.

"Looking back and look at how parliament is now and the changes that still need to be made, I think it's great to look back at history and what those women won, and to think what the women in parliament can now win for future generations."

A stained glass window in the parliament marks the women's suffrage movement

Just beyond the New Dawn artwork, beside all the statues, there's a stained-glass window documenting changes to the franchise in the UK.

It starts with the suffrage movement and ends with the 1997 devolution votes.

Clearly, a considerable amount has changed over the century the window represents.

Many though, think much more is needed.