What's the latest on the Brexit powers row?

- Published

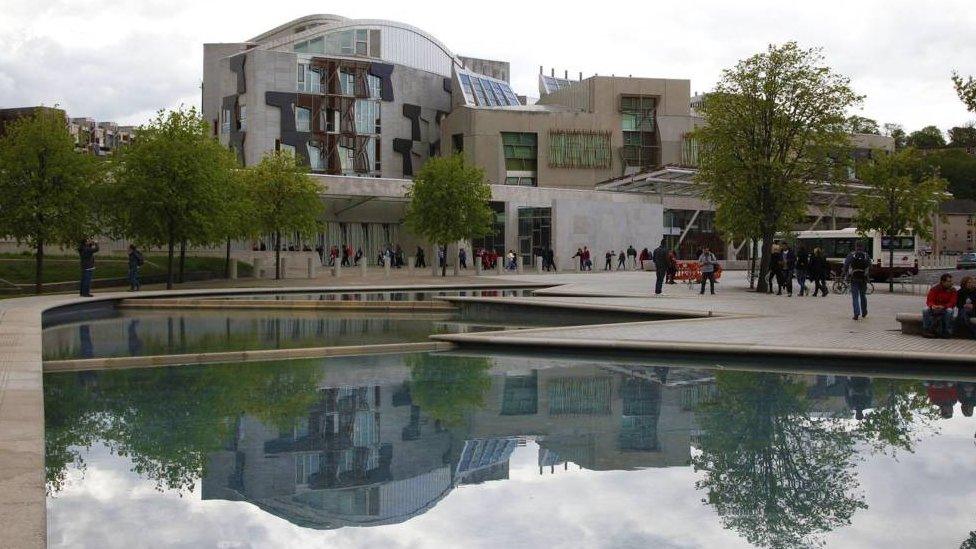

MSPs have refused to give Holyrood's devolved consent to the EU Withdrawal Bill, the main piece of Westminster Brexit legislation. What is the background to the row, and where might we end up?

What's this all about?

The row centres on a set of powers which are technically devolved to the Scottish Parliament, but which are currently exercised from Brussels to ensure rules and regulations are the same across the EU.

The question is what happens to these powers after the UK leaves the EU?

Ministers agreed that some of them should go into UK-wide frameworks - similar to how they were used previously but across the UK's "internal market" instead of the European one.

The argument is about how these "UK-wide frameworks" are set up and how they might be run in the years immediately following Brexit.

What sort of powers are we talking about here?

They fall into areas like farming, fishing, environmental regulations and public procurement.

An example would be food standards. Minimum standards are agreed for specific products like coffee, honey, condensed milk, chocolate and jam.

At present, these apply across the EU - and post-Brexit, UK ministers want to agree common standards to apply across the UK.

A similar field is food labelling - a common approach to what information is included on the label on the back of your tin of beans or packet of mince, and how it is presented.

Time has all but run out for Scottish and UK ministers to come to an agreement

What is the dispute about, then?

The row is about how these common frameworks are set up, and who has the final say over them where ministers fail to agree.

UK ministers say that some areas are so important that in the first few years after Brexit, they can't afford splits in that "internal market" over things like food standards.

They say that if there isn't agreement on a shared area, someone has to make a decision - and that someone should be the Westminster parliament, acting for the UK as a whole.

Scottish ministers reckon this is a "power grab", leaving Westminster free to impose its will on Holyrood.

Scottish Brexit minister Mike Russell said this would give UK ministers "a totally free hand to pass legislation that would directly affect Scotland's fishing industry, our farmers, our environment, our public sector procurement rules, the safe use of chemicals and our food safety," while Holyrood's "hands would be tied".

It boils down to one word - "consult", or "consent". Do UK ministers have to get the explicit consent of the devolved administrations for action in these areas, or just consult them?

One word? Shouldn't this have been easily settled, then?

Well, not really. Both sides rather dug in around their positions, and each claim the other side's preferred word would represent a significant change to the existing devolution settlement.

UK ministers say the "consent" route would effectively give ministers in Edinburgh (or indeed Cardiff or Belfast) a "veto" over things happening in other parts of the UK.

Scottish ministers contend that the "consult" route would let Westminster overrule them on important devolved issues.

Constitutional scholars will note that technically, the UK parliament has the power to do this already - the Scotland Act notes that they would "not normally" do it, which doesn't rule it out - but ministers don't want to open up another route for that to happen.

There's a question of trust as well as wording - Mr Russell says it's all very well for the Theresa May government to make commitments not to mess the devolved administrations around, but what about future administrations? The Boris Johnson government, or the Jacob Rees-Mogg government?

Picking a fight with a possible future government "sounds ridiculous", Mr Russell admits - but then, "we live in a very bizarre world".

UK and Scottish ministers remain some distance apart despite a series of summits

Isn't there room for compromise here?

Both sides say they have already compromised.

Mr Russell says the Scottish government compromised just by accepting the idea of UK-wide frameworks.

UK ministers, meanwhile, offered a "sunset clause" time limit on their plans. This would put a two-year time limit on the power to make new regulations in devolved areas, and a five-year limit on the regulations themselves.

However, as much as the two sides might have moved towards each other, they haven't met in the middle. The "sunset clause" is still seven years too long from the Scottish government perspective.

So why did the Welsh do a deal?

At one time, the Scottish and Welsh governments coordinated their opposition to the Withdrawal Bill "power grab". Joint statements were published, legislation passed in tandem.

But then, Welsh and UK ministers have found "a deal we can work with".

The Welsh accepted that some powers will be "temporarily held by the UK government", in areas where "common UK-wide rules are needed for a functioning UK internal market".

There were perhaps as many political reasons for the deal as constitutional ones.

Welsh First Minister Carwyn Jones had just announced he was stepping down. Mark Drakeford, who has led in the talks with UK ministers, is gunning for the top job. On top of that, a majority of Welsh voters backed Leave in the referendum - meaning ministers in Cardiff have a slightly different set of priorities.

The Welsh Assembly has also only just moved to the "reserved powers" model of devolution which Holyrood has used from day one, having previously used the "conferred powers" model. Having just had one big change to their devolution settlement, another alteration might be easier for the Welsh to swallow.

Carwyn Jones and Nicola Sturgeon used to work together on Brexit - but now the Welsh have done a deal

Is there any more time?

A whole series of deadlines have come and gone, but ministers always seem to insist there's still time for a deal to be done (if only someone else would give in).

Tuesday was the deadline for the devolved parliaments to give their consent to the bill, before its final reading in the Lords. MSPs at Holyrood said no; reflecting their deal, AMs in Wales said yes.

Despite this, both sides say there is still a little time. The consent votes were only on the Withdrawal Bill as it currently stands, and it is not yet the finished article. The bill still has to bounce between the upper and lower chambers at Westminster while amendments are ironed out.

So technically, there is still some time. But it increasingly feels like neither side really have their heart in it any more - there's just too much distance between them. It would take something completely new to break the deadlock at this point.

So what happens now?

If there is no deal, then there are two places we could end up.

Either the UK government presses ahead and legislates anyway, without Holyrood's devolved consent, or they let it slide and let the Scottish Parliament's own legislation fill in the gaps in the law north of the border.

The "continuity bill" was passed by MSPs as a backstop, an alternative to the Withdrawal Bill should they end up refusing consent for the Westminster version.

However, UK law officers have challenged that legislation in the Supreme Court, questioning whether it falls within Holyrood's remit.

One possible outcome is that the justices shoot down the bill, at which point UK ministers would say they have no choice but to legislate for Scotland regardless of consent.

What if the justices allow the Holyrood legislation to proceed? Well, Westminster could go ahead and legislate across devolved areas anyway - they have that power. The devolution settlement says they would "not normally" do this, but ministers could argue that these are not normal times - if they could live with the massive row which would ensue.

Or they could let the continuity bill stand. This would give Scottish ministers extra leeway to go their own way on matching up regulations with EU ones, or ones in the rest of the UK - something which may not be palatable for UK ministers, given their arguments about the "internal market".

- Published24 April 2018