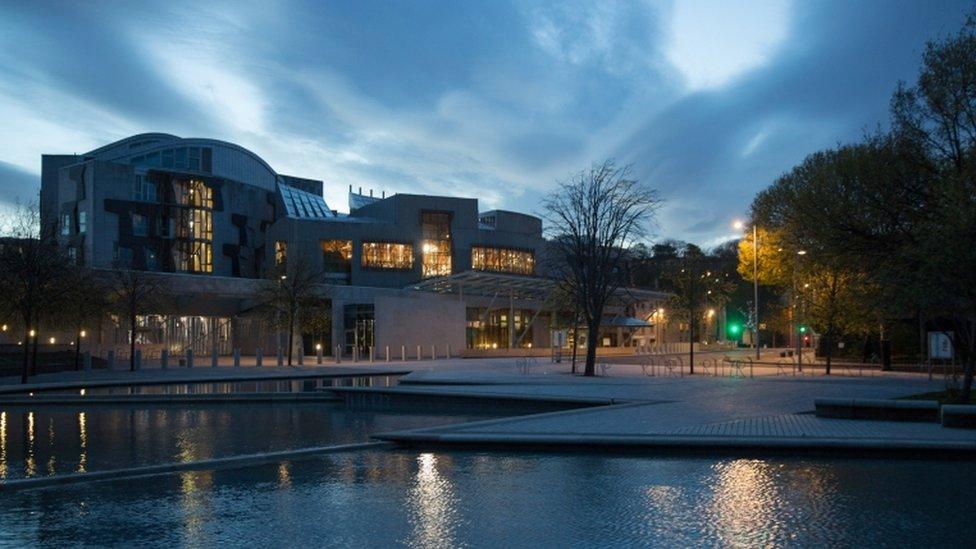

Scotland and Brexit - what happens next?

- Published

MSPs are set to refuse consent for the EU Withdrawal Bill, setting up a constitutional stand-off

How much does it matter that the Scottish Parliament has voted to reject the EU Withdrawal bill?

The Scottish government insists this is a highly significant moment, as it is the first time the Holyrood parliament has ever refused consent to a piece of Westminster legislation which is likely to be imposed anyway, without consent.

It is certainly a constitutional first - but one that can be overcome by Westminster.

The UK government has the authority to simply impose the Brexit legislation on Scotland, even if that is politically problematic. It would overturn 20 years of constitutional convention and precedent.

They didn't want to find themselves in this position. The exhaustive hours of negotiations endured by very senior ministers shows how much they wanted to find a compromise and avoid this constitutional clash.

At the very time that Theresa May is restating her deep commitment to the union - in relation to Northern Ireland - it's awkward to be simultaneously forcing her Withdrawal Bill on Scotland. Especially as any Brexit legislation isn't very popular in a country that voted 62% to remain in the EU.

But this prime minister has ignored the will of the Scottish Parliament before. This time last year it voted in favour of a second indyref and the PM said no. There was no noticeable uprising of popular outrage then. And there is unlikely to be so now.

SNP ministers maintain this dispute, over who gets to exercise particular powers in areas such as agriculture and the environment, goes to the very heart of the principle of devolution.

'Standing up for Scotland'

And they hope to persuade people it's not just an abstract constitutional argument as the powers in question cover significant policy areas like farming, food and drink and environment protection.

Nicola Sturgeon rarely shies away from a fight with Westminster. It's generally good politics for her to say she is "standing up for Scotland" against ministers in London. She hopes it helps build the case for why Scotland would be better off as an independent country.

In this battle, she will be joined by Labour, Green and Lib Dem MSPs who all intend to vote with the SNP government.

Her problem is that this argument has not caught voters' attention. The right of the Scottish Parliament to have a definitive say over regulations governing the use of pesticides does not appear to cause great concern to Scots.

Some may be outraged over the principle of legislation being imposed on Scotland after it has been specifically rejected by their MSPs. The practical consequences may not amount to much. Yet it is one more headache for Theresa May in the migraine-inducing process of trying to secure a Brexit deal.