Dull as ditchwater? Inside Holyrood's forgotten committee

- Published

A stretch of water which has a historical pedigree dating back to the 13th century

The Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission Bill Committee met for what might be the final time, external at Holyrood on Wednesday. Is this Scotland's most boring political assembly, or its best-kept secret?

What is the Pow of Inchaffray?

Well, it's a ditch. Quite a long drainage ditch, which channels groundwater from a patch of Perthshire into the River Earn.

Its tributaries run for a total of 13.7 miles, and drain 2,047 acres of land. Which, to use the standardised unit of measurement, is about 965 football pitches.

The history of this pow - a versatile Scots word, external, in this case meaning artificial ditch - runs right back into the Dark Ages.

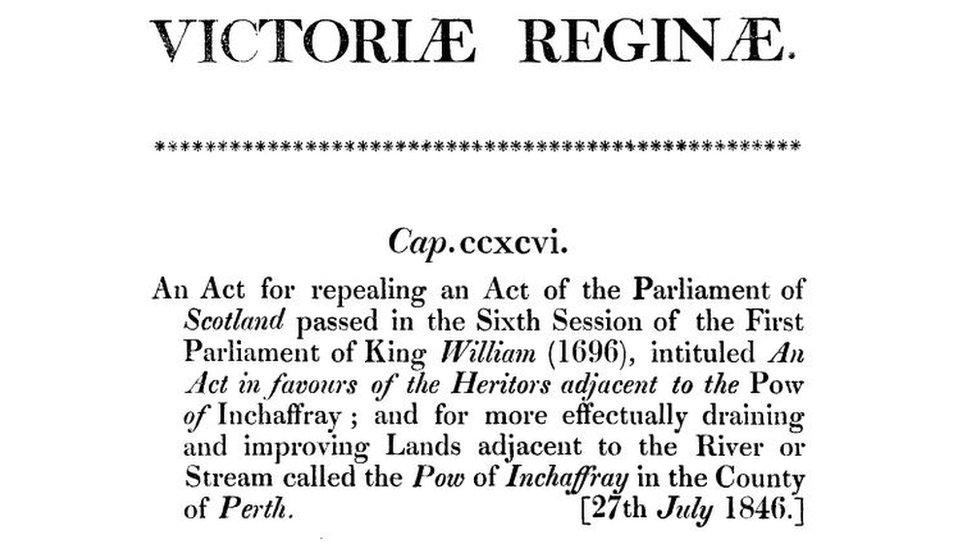

The bill currently being considered by this obscure Holyrood committee repeals a 172-year-old piece of legislation, which itself superseded a 322-year-old Act of the old Scottish Parliament.

The people bringing forward the new legislation say the land cleared by the pow is "among the most fertile agricultural acreage in Scotland", and say it is "vitally important that the pow is maintained to prevent flooding in this area".

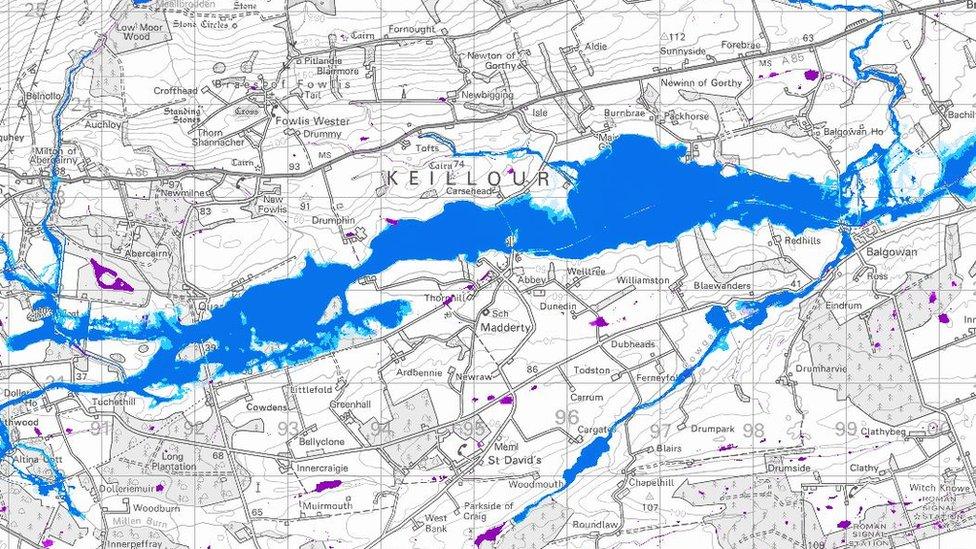

There is a sub-row about what the pow is actually for - involving the technical difference between groundwater drainage and flood prevention - but the Scottish Environment Protection Agency's map of flood risk areas, below, underlines that parts of the local area could, in the wrong circumstances, more or less be a lake.

SEPA's flood risk map underlines the danger of flooding in the area drained by the pow

History

Maurice of Inchaffray blessing the troops at Bannockburn

The pow itself dates back to the 13th century. It was dug by Augustinian canons as part of the building of Inchaffray Abbey, sometime around 1200 AD.

The abbey itself - at one point one of the largest in Scotland, home to upwards of 200 monks - was built on an island in a marsh, which the canons endeavoured to drain by digging out the beginnings of the pow.

Maurice, an Abbot of Inchaffray, was chaplain to one King Robert the Bruce, and blessed the troops on the battlefield at Bannockburn.

Legend has it that the abbot brought along a reliquary of Saint Fillan, external, but left it empty for fear of it being captured by the English - and that the saint's arm-bone miraculously appeared in it regardless, inspiring the Bruce to victory. Later that year, 1314, the grateful king ordered an extension to the pow by way of thanks.

After the Reformation and the abolition of the monasteries, the abbey eventually fell into ruins (which were, at one time, rumoured to be haunted). But the pow lived on, and entered the statute books in 1696 via an "Act in favour of the Heritors adjacent to the pow of Inchffray".

This legislation formally recognised the importance of the pow, and created formal posts for drainage commissioners to tax all of the local "heritors" - people who own local land or property which benefits from the drainage ditches.

The original Act was updated in 1846, but there have been many developments since then - not least the re-establishment of the Scottish Parliament, and the construction of many new houses in the area. And so MSPs are considering a new piece of legislation to bring the law up to date.

The bill

To briefly get technical, the Pow of Inchaffray Drainage Commission (Scotland) Bill, external is a private bill - one not proposed by the government or even an opposition MSP, but by the drainage commissioners themselves.

It sets out procedures for the appointment of commissioners, identifies the land benefitting from the drainage, sets out how much money has to be collected, and from whom, and gives the commissioners powers to recover debts via the courts.

The bill has had some key questions to answer. How should the costs of maintaining the pow be shared out? Who should have to pay, and how much? And should something be done about some pesky beavers?

Meet the committee

MSPs from the bill committee - the trio on the right - visited the Pow to see the site first-hand

On the face of it, one might wonder why the management of a ditch should have to be legislated for in the nation's parliament.

Basically, nobody else wants the job.

SEPA say it wouldn't be within their remit. Perth and Kinross Council say they wouldn't be willing "at this time of austerity and reducing budgets". Scottish Water didn't even reply to the commissioners when they first wrote to them, leading them to conclude that the group had "no intention or interest in taking on responsibility for the pow".

So it comes down to this, a private bill overseen by a cross-party team of three MSPs - the SNP's Tom Arthur, Labour's Mary Fee and Tory Alison Harris.

It's fair to say the rest of the parliament has not been gripped by the matter. In the first parliamentary debate on the bill, the three MSPs on the committee were the only ones who came forward to speak, and energy minister Paul Wheelhouse only managed to stretch his response out over a single minute by quoting at length from the committee's report.

This is likely to be repeated come the final debate, sometime later this year. But the lack of fuss in parliament has been more than made up for at committee level.

The debate

A large housing estate has been built at Balgowan, near the Pow

The passage of the bill has not been plain sailing. When a private bill goes through parliament, ordinary citizens can object to its terms - and a succession of pow "heritors" did so.

The committee of MSPs had to adjudicate on their complaints, which ranged from people claiming they shouldn't have to pay, to disputes about the dispute resolution measures.

The committee took a "quasi-judicial" role over the objections, with the commissioners and complainers duking it out in a committee room while the MSPs watched on.

Some other locals also came forward with comments - including one man who raised concerns that the land plans submitted by the commissioners were inaccurate. It turned out they were based on plans from 1851.

MSPs said the blunder undermined their "confidence in the expertise and credibility of the commission, not to mention the confidence the heritors should have in the commission".

However, they said they were "impressed with how thoroughly and helpfully the commission responded to this situation", and hoped they had "learned from this experience".

Another problem has been posed by beavers, which were illegally released into the area 10 years ago. There have been proposals to install "beaver barriers" on the pow, but cost estimates have risen above £40,000 - a financial commitment which led Scottish Natural Heritage to walk away from a proposed trial project.

Why should we care?

Is this muddy ditch a symbol for the state of modern politics?

Ok, if you don't happen to live nearby, it's unlikely that the Pow of Inchaffray is going to be an issue which grips you on a daily basis.

But in many ways, this is exactly what government is for.

We're talking about the administration of a communal resource; a complex task which nobody seems to want to take responsibility for.

It concerns property both public and private, involves taxation, and there are a myriad of disputes over who should have to pay and how much.

This is precisely what elected representatives are for. It's textbook stuff.

Among all the thunder and fury of constitutional rammies and increasingly partisan rows, shouldn't we find it reassuring that this kind of work can still quietly go on - and on a consensual, cross-party basis?

It might not be the sexiest issue, and MSPs aren't queuing around the block to make speeches about it. But this, right here, is the day job.