Reality Check: Has the UK's devolution settlement been ripped up?

- Published

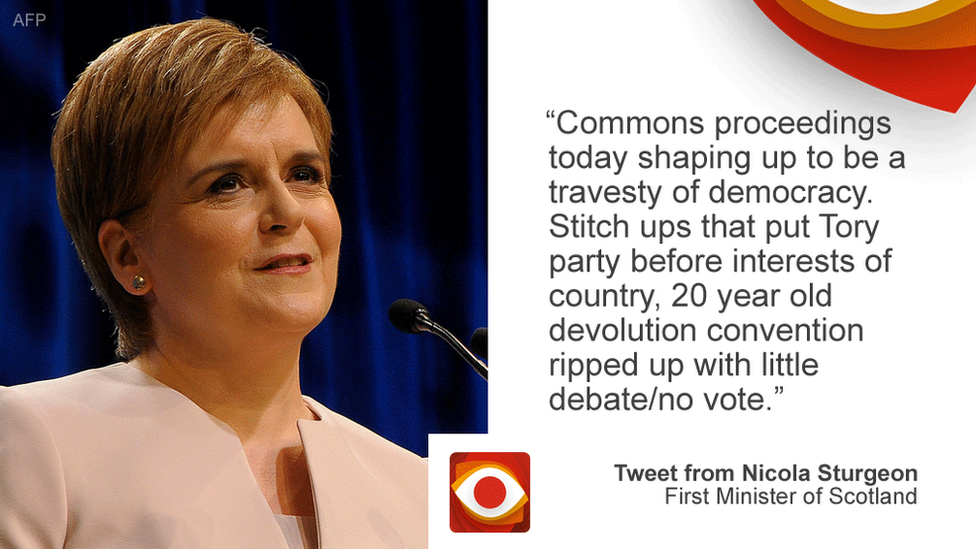

The claim: The UK's 20-year devolution convention has been "ripped up".

Reality Check verdict: The convention has been undermined but there is no legal reason why the UK government cannot ignore the Scottish Parliament over Brexit.

Scotland's first minister says the passage of the UK's key Brexit legislation without the consent of the Scottish Parliament has "ripped up the 20-year-old devolution convention" in the UK. Is she right?

Ms Sturgeon's tweet came after the House of Commons spent less than 20 minutes debating the EU Withdrawal Bill's impact on devolution.

The SNP said that showed "contempt for Scottish democracy", with the party's Westminster leader, Ian Blackford, leading a walk-out of his MPs during Prime Minister's Questions on Wednesday.

The row centres on a so-called "power grab", with the Scottish government accusing Westminster of keeping some powers for itself that should go to the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, after Brexit.

Rules and regulations

The UK government says the "temporary" move will allow the same rules and regulations to remain in place across the whole of the UK in 24 key areas, such as agriculture, fisheries and food labelling.

And it points out that the vast majority of the 153 areas where policy in devolved areas is currently decided in Brussels will go directly to the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly, meaning both will have considerably more powers after Brexit than they do now.

Months of talks have failed to reach a deal - although the Welsh government dropped its opposition after changes were made that would put a limit on how long the UK government would keep the powers.

Last month, the Scottish Parliament voted overwhelmingly to refuse consent for the Brexit bill, with the SNP being joined by Labour, the Greens and Liberal Democrat MSPs and only the Conservatives voting against.

SNP MPs walked out of the Commons on Wednesday

The UK government pressed on regardless - so how was it able to do so?

When the devolved Scottish Parliament was set up in 1999, it was handed control over many policy areas such as health and education that had previously been decided at Westminster.

However, an agreement signed by the two governments in 2001 stated that "the United Kingdom Parliament retains authority to legislate on any issue, whether devolved or not" and that it was "ultimately for parliament to decide what use to make of that power".

It also stated that the UK government "will proceed in accordance with the convention that the UK Parliament would not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters except with the agreement of the devolved legislature".

A protest against the so-called "power grab" was held outside the Scottish Parliament earlier this year

This agreement was inserted into the Scotland Act in 2016, which was drawn up after the independence referendum two years earlier.

The word "normally" is, of course, an important caveat that is open to different interpretations - is Brexit "normal", for example?

Scottish Secretary David Mundell said these were not normal times and a failure to proceed with the bill would jeopardise businesses across the UK.

He accused the Scottish government of wanting a veto over arrangements that would apply to the whole of the UK and insisted the UK government "followed the spirit and letter of the devolution settlement at every stage" despite the failure to secure consent.

Consent is sought through something known as the Sewel Convention, named after former Labour government minister Lord Sewel, which, in effect, allowed the UK government to ask MSPs for permission to change the law in an area that is devolved to Holyrood.

Similar conventions apply in both Wales and Northern Ireland.

Until Brexit came along, the Scottish Parliament had only once before refused to give its consent - over some aspects of the Welfare Reform Bill in 2011, which resulted in the Scottish government introducing its own legislation to resolve the row.

So Ms Sturgeon is correct to say that pushing through the EU Withdrawal Bill without the consent of the Scottish Parliament means that the long-standing convention has, in effect, been "ripped up".

Supreme Court

However, as its name suggests, it is merely a convention and there is no legal requirement for the UK government to seek Holyrood's permission - or to respect its decision if it says "no".

This was confirmed by the Supreme Court last year, when it ruled on the case brought by Gina Miller about the triggering of Article 50, which started the Brexit process.

Judges ruled that the Sewel Convention was not a legally enforceable rule despite being inserted into the Scotland Act.

This meant that the Scottish Parliament did not have a veto over Article 50 or, by extension, the EU Withdrawal Bill.

Regardless, ignoring the result of the Scottish Parliament vote was sure to provoke fury from the SNP, with Ms Sturgeon warning that "the decision to act without our consent, and the manner of doing it, will not be forgotten".

- Published13 June 2018

- Published12 June 2018