Mental health services 'let down children'

- Published

The average length of time children have to wait for specialist mental health treatment has increased in recent years

The Scottish government has admitted that children and young people are being "let down" by the country's mental health services.

Child mental health has been a key priority for the government as part of its goal of making Scotland the best country in the world to grow up in.

But a watchdog's report has found that specialist services are struggling to cope with increasing demand.

Mental Health Minister Clare Haughey said the situation was "unacceptable".

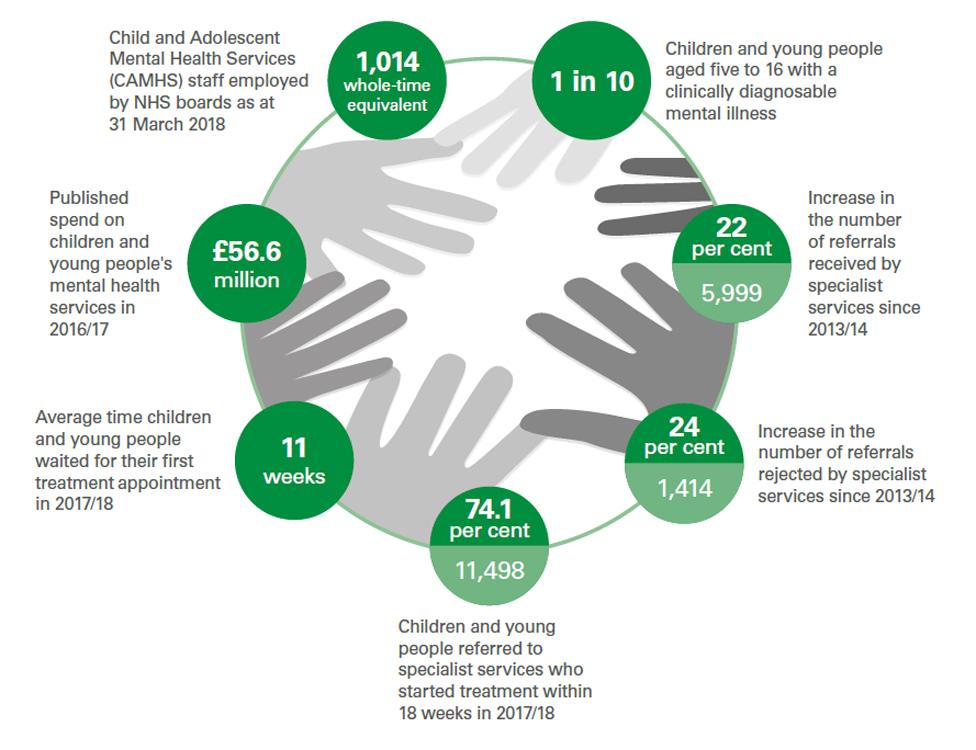

The Scottish government's target of having 90% of children and young people start treatment within 18 weeks of being referred to specialist mental health services has never been met since being introduced in December 2014.

Instead, waiting times have increased since the target was set - with 26% waiting longer than 18 weeks last year, compared to only 15% in 2013/14.

Meanwhile, average waiting times for a first treatment appointment increased from seven to 11 weeks between 2013/14 and 2017/18.

Data published earlier this month showed waiting times were the worst on record between April and June.

About one in 10 children aged between five and 16 in Scotland are said to have a clinically diagnosable mental illness, and there has been a 22% increase in the number being referred for specialist treatment in recent years.

The number of rejected referrals has also risen, by 24% since 2013/14.

In a joint report published on Thursday, Audit Scotland and the Accounts Commission said children may receive "little or no support or advice" while they are waiting for treatment.

This can cause their condition to deteriorate or make it more likely they will drop out of the system during the process.

The report called for a "step change" in how the the government, councils and health boards respond to the mental health needs of children and young people.

It said the government's mental health strategy - which focuses on early intervention and prevention - was "limited" in practice.

The reality is that mental health services for children and adolescents are instead largely focused on "specialist care and responding to crisis", the report said.

'Complex and fragmented'

But it described the system as "complex and fragmented" with access to specialist support services varying throughout the country, which can make it difficult for children and their families to get the help they need.

The report also said that early intervention services such as school counselling and primary mental health workers are patchy across the country.

And it said teachers and other people who work with children need more mental health training.

Meanwhile, poor financial and performance data means it is difficult to identify how much is being spent on services or the difference they are making to young lives.

Ms Haughey said she would accept all of the report's recommendations

Ms Haughey welcomed the report and immediately pledged to implement all of its recommendations, adding that "too many children and adolescents are being let down" by the current system.

She said: "I have been clear that this is unacceptable and that we must look at making the changes necessary to ensure young people get the care they need and deserve."

Earlier this week, a government-appointed taskforce made a series of recommendations including immediate action to address issues with rejected referrals, a stronger focus on prevention and early intervention, and better data quality.

Additional funding will help provide counsellors in every secondary school, 250 more school nurses and training for teachers among other measures.

Scottish Conservative mental health spokeswoman Annie Wells said: "We've had plenty of warm words from the SNP government on this, but it's now time to see these changes actually happen."

Scottish Labour health spokesman Anas Sarwar said: "The additional funding and counsellors announced in the program for government is a start, but it is clear we are still some way off seeing mental health services treated with parity of esteem with acute services."

The Scottish Children's Services Coalition, which campaigns to improve services for vulnerable children, said the "dismal" state of mental health meant many children young people "are simply not getting the care and support they need, when they need it".