Doing the maths on the meaningful motion

- Published

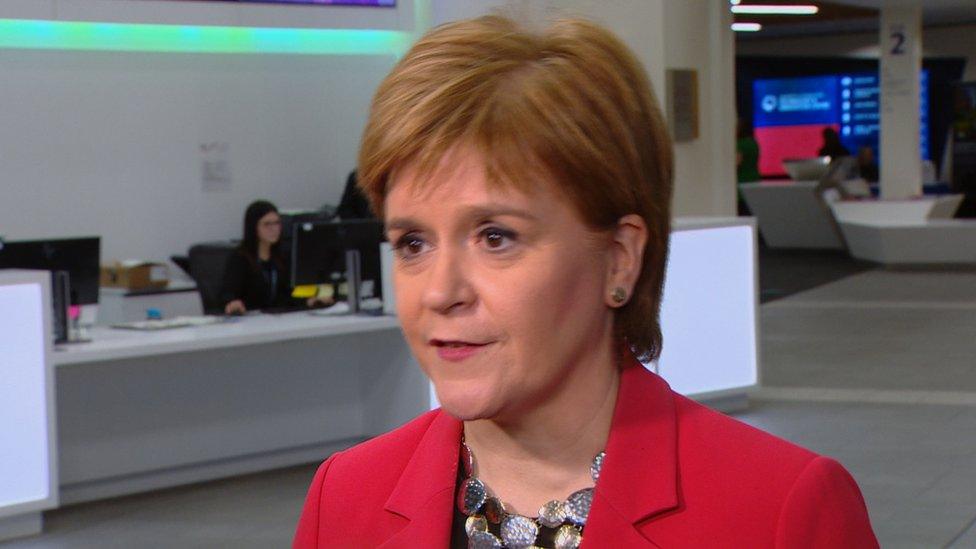

Nicola Sturgeon: "This, from what I know of it, [Brexit withdrawal text] is not a good deal for Scotland."

Early reaction to the Brexit outline agreement? Not, it has to be said, bubbly and joyous. Seldom has the political atmosphere seemed more remote from Browning's glad confident morning.

That includes the response from the first minister who said the draft deal advanced by Theresa May was, on the face of it, "the worst of all possible worlds".

There has long appeared to be a tendency within the Brexit discourse to opt for the apocalyptic in tone. Reaction to the latest move is no exception.

For example, Boris Johnson summoned up "one thousand years of history" in condemning the outline deal. It's always millennial, isn't it?

To get this agreement through her cabinet - which meets this afternoon - and, even more so, the Commons in a few weeks, Theresa May is going to depend upon shedding the apocalypse and replacing it with reluctant, possibly sullen pragmatism.

Even her most loyal ministers seem reflective, rather than eager, at this early stage. David Mundell, the Scottish secretary, said the news of a technical agreement was "encouraging".

Scarcely the note of zeal the PM might have been hoping to hear but positively bullish by comparison with the comments from elsewhere in the Tory firmament.

Firstly, the cabinet. There are concerns that the deal might tie the UK into long-term EU links. There are concerns over the economic consequences. There are concomitant anxieties about strains on the Union that is the United Kingdom.

Then, the Commons. There is to be a "meaningful" vote (different, apparently, from the futile piffle which frequently masquerades as debate. Oh, Brian, enough).

Theresa May faces a fight to get her deal through her cabinet - and then through the Commons

There is a serious - and substantive - argument over whether that meaningful motion should be open to amendment.

Those who say yes argue that it would be monstrous - and unconstitutional - to prevent MPs from amending a proposal before the house.

Those who say no argue that the Commons is not the sole arbiter. That the deal will, in effect, be a treaty negotiated by Her Majesty's government under executive powers. That there is another party, the remaining EU members.

That, consequently, it is not practical for the Commons alone to amend a deal which is the result of prolonged bargaining with an external party.

But there is a prior issue to all of that, important though it is. Will the Commons back the deal? Or will it, collectively, declare: up with this we will not put?

Opposition from the opposition

Opposition parties have particular and distinctive motivations for voting no. Of course, the initial clue is in the word "opposition". But there are clear, precise factors at play.

Labour will vote no because its objective is to bring about a UK general election. The Shadow Scottish Secretary Lesley Laird made that amply and repeatedly clear on the wireless this morning.

She was, perhaps understandably, a little more opaque as to what would happen next. Not with the governance of the UK: she envisaged that falling into Labour hands. But with Brexit. It would not go away simply because there is a change of government.

That mandate from the referendum would still exist. Article 50 would still have been triggered. So, a general election. Perhaps a change of government. And then?

Labour's Lesley Laird said her party's goal was a general election

One supposes that Labour would seek to negotiate a different treaty, presumably securing the agreement of the other 27 to defer Article 50.

Would that work? Labour's six tests on Brexit, set out in 2017, include the aim of ensuring the retention of the same benefits as currently apply to the UK in the EU single market. But is that feasible in that Brussels has explicitly set out to prevent such an objective, fearing fragmentation elsewhere on the continent?

The Liberal Democrats will vote no, largely because they want to achieve a further referendum on the terms of the exit deal, what they term a "People's Vote." The SNP have now backed that notion and perhaps, over time, it will win added favour in Labour and Conservative ranks.

There are different interpretations as to what such a vote might constitute. Would it be yes or no to the terms? Or the Brexit terms versus remaining in the EU? Or a multiple option ballot? Right now, the UK government is against such a vote - as is the Labour leadership - but it might not be entirely in their hands.

'Worst of all worlds'

Then there is the SNP. Also on the wireless this morning, Ian Blackford, the party's Westminster leader, was admirably clear. The SNP wants to retain EU membership in line with the voting pattern of the Scottish people.

Failing that, their minimum requirements are full membership of the single market and the customs union. Mr Blackford sensibly surmised that such an outcome would not feature in the agreement to go to the UK cabinet this afternoon.

And the "worst of all worlds" verdict delivered by Nicola Sturgeon? This is a reference to Northern Ireland. The suggestion is that there might be distinctive treatment in some form for NI, tying it more closely into EU trade.

Such a position is anathema to Theresa May's supposed allies, the DUP. But Ms Sturgeon is concerned for a different reason.

She says that Scotland would be removed from the EU single market - while competing for jobs and investment with Northern Ireland which, she says, would be "effectively" inside that EU arrangement.

The opposition will likely oppose - but will Theresa May be able to win over her own backbenchers?

So, calculating the Commons arithmetic, Mrs May can expect the opposition parties to oppose. She needs to get all of her own ranks in line, including the reluctant DUP. And, right now, they are not there. Right now, the commons sums are against her.

Could that change? Perhaps. So far, we have heard from the critics. That tends to be the case. The quiet ones who favour the agreement or simply want the nightmare to end have yet to speak. They might be there in number for Mrs May, eventually.

Secondly, is it possible that the passage of time - and perhaps a nervous reaction from the markets to any problems with the deal - might sway minds, either on the government or opposition sides? Again, perhaps.

Right now, that looks highly unlikely. But then again, right now, we are mid-apocalypse in terms of reaction. Perhaps that might calm down. Perhaps.

One scenario suggested to me is that the prime minister loses that "meaningful" vote in the Commons. She then calls a confidence vote, putting her own future on the line (it is, of course, already there).

She wins that vote because Tories dislike the idea of a hazardous election and the DUP dislike the thought that Jeremy Corbyn might become prime minister, with influence over Northern Ireland affairs.

Then she tries again on the Brexit deal. Spooked, enough Tories and perhaps Labour members - who gave it one shot on bringing about an election - fall into line for the deal to pass.

Desperate stuff, I know, but that is where we are now. Considering the seemingly ludicrous because calm discourse has long since deserted the scene.

And what about Scottish independence? Nicola Sturgeon has promised to update us on her thinking when there is clarity over Brexit.

Do you believe we are at that stage yet? Thought that might be your reply.

- Published14 November 2018

- Published14 November 2018