May's Brexit strategy: Tedium and terror

- Published

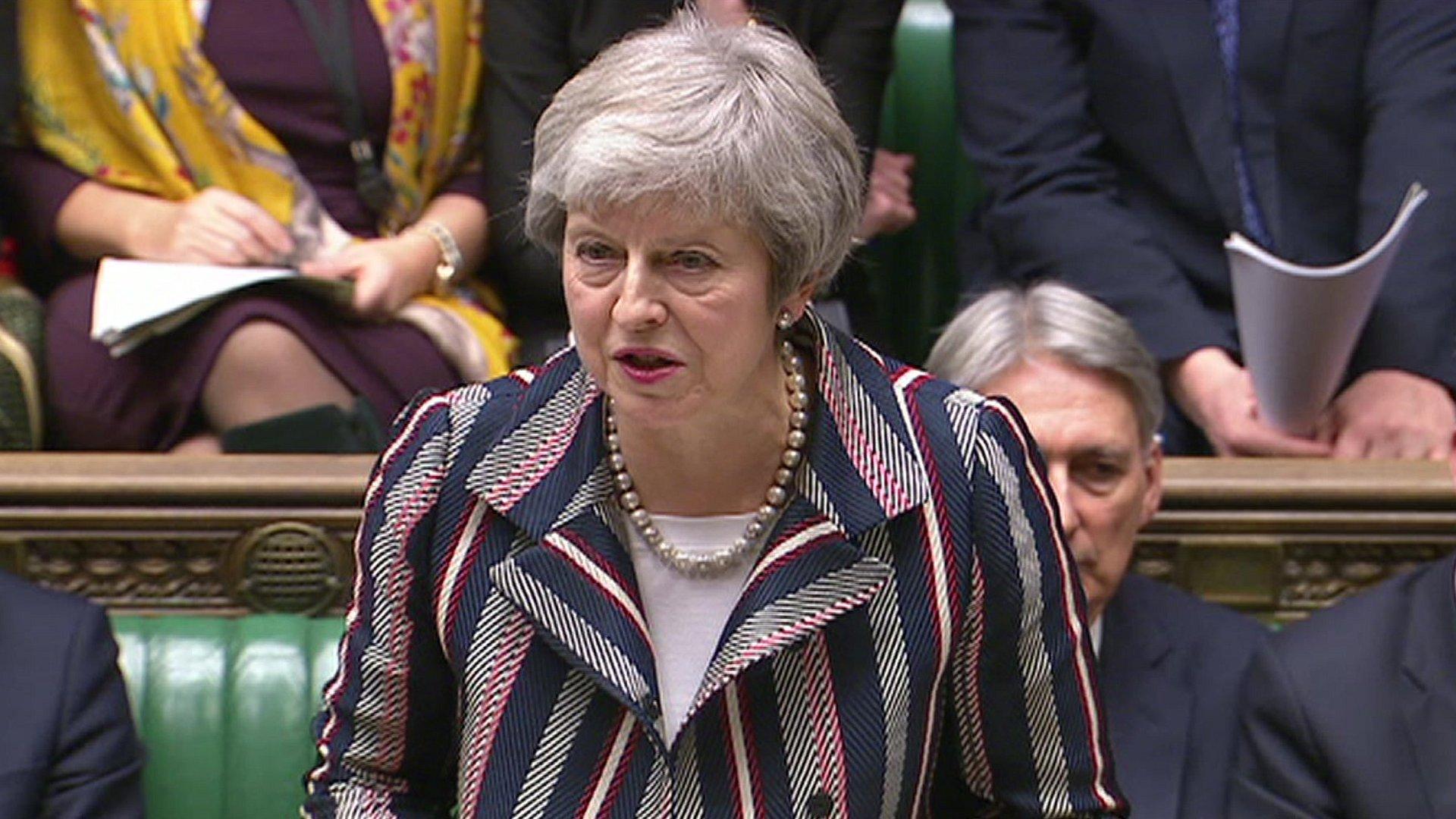

Theresa May faced another gruelling session in the Commons

Remember the Rorschach test? You know, the one where folk are shown random inkblots and asked to describe what they see?

Some spot a sparrow landing on a roof. Some, looking at the same squiggles, see Hannibal crossing the Alps, complete with elephants.

Perception matters. So try another test - as yet, without a posh scientific name. When you think about Brexit, what are the words which spring instantly to mind?

No cheating, now. No looking up the political declaration or the 585-page withdrawal agreement. What leaps instantly to mind? Ah, now, there's no need for language like that.

Seriously, one hates to pre-empt this valuable scientific experiment. But I would simply express gentle doubts that the phrase on most people's lips is "smooth and orderly".

And yet these were the "mots de jour" for the prime minister in the Commons as she spelled out the details of her deal with the remaining 27 EU members.

By my count, she said "smooth and orderly" at least three times. There may have been more such occasions. The widespread reaction from MPs, it has to be said, was scepticism.

So, given that, how to get this deal past the Commons? The PM's strategy seems to swerve, vertiginously, between tedium and terror.

How many of Theresa May's backbenchers will back her in December's vote?

Firstly, the tedium. Folk, she implies, are heartily sick of hearing about Brexit. They want to "move on" (another phrase she used with comparable repetition). Only the pesky Commons was preventing this. They should desist.

Secondly, terror. This has two phases. The PM asserts that there is no alternative (c. Thatcher, M, 1981 et al).

She told MPs today: "I can say to the house with absolute certainty that there is not a better deal available."

All around her, many heads shook gently as MPs - on the government benches and opposite - seemed to question the very nature of existence, never mind the certainty of the statement made by the PM.

An unwanted backstop

From that, Theresa May moved to the alternatives. She has previously characterised these as No Deal or No Brexit. A multiple appeal to different audiences.

Today, once again, she argued that rejecting her deal with the EU27 would be to "go back to square one". There would be "division and uncertainty". It was, as more than one MP suggested, a form of Project Fear (to be clear, that does not make it an illegitimate tactic for a PM in trouble).

On various fronts, the PM found language which was sometimes direct, sometimes nuanced. On the Northern Ireland backstop, she essayed both simultaneously.

The deal, she insisted, protected the integrity of the UK. But then, in the next breath, she noted its flaws. Or, to be precise, the drawbacks in the backstop.

Nobody truly wanted it, she said. Not the UK which wanted to strike a longer-term trade agreement, thus obviating the need for the customs-membership backstop.

But not, in addition, the EU, some of whose members suspected that retaining access to the customs union might give the UK an unwarranted advantage.

Theresa May on Northern Ireland backstop: "This is an insurance policy on-one wants to use."

So why back a deal which nobody liked? Because, she explained, this disquiet guaranteed that there was an incentive to strike a full-scale trade deal. It has, I suppose, a logic of its own.

On the question of whether Brexit will damage or bolster the UK, Team May has found the formula which has appeared to elude them thus far.

The economy, she argued, could be boosted by Brexit. But departing the EU would not be the determining factor. What counted was the future endeavour and aptitude of the British people, not Brexit per se.

On Gibraltar, she lauded the Rock's chief minister - and, in return, quoted his praise for the efforts of the UK government.

Fishy business

And fish? Ian Blackford (and, before him, Jeremy Corbyn) said the agreement amounted to a complete sell out of the industry. Mr Blackford, naturally, majored upon the Scottish impact.

The SNP Westminster leader said it was but the latest in a long line of betrayals by what he would undoubtedly characterise as "perfidious Albion".

Mrs May had two replies. One, that the EU leaders had tried - and failed - to gain guaranteed access to British waters.

Yes, they were again talking up this prospect (she meant you, M. Macron). But they would get the same answer. A tie-up on mutual access was not going to happen. Cue those shaking heads again.

To Mr Blackford, she said that the true betrayal would be the SNP's desire to return to the Common Fisheries Policy. Had Mr Blackford been granted a further question, he might have stressed his party's support for widespread reform in this area.

Ian Blackford charges the government with selling out the fishing industry

Backbench Tories, many of them only recently returned to that status, lined up to object that the deal would leave Britain subject to EU rules, under the backstop, without gaining any advantages. Smooth and orderly would not have been their answer to the test.

Which leaves us where? As things stand, Mrs May will not win the support of the Commons in a vote presently scheduled for December 11.

Labour's Jeremy Corbyn said no. Ian Blackford of the SNP said no. Several Tories said no. For the Liberal Democrats, Vince Cable urged a further referendum.

One or two even suggested that Mrs May should give up now - and get the renegotiation under way. With droll and understandable irony, she noted that most had told her she would never get a deal with the EU27. Now she faced demands for Plan B, one day after Plan A was achieved.

Commons calculations

So what can she do? She is absolutely entitled to put her package to the Commons. If that results in defeat, she has a range of unpalatable options.

She has a further 21 days in which to draft an alternative approach. Perhaps she might try - again - to tweak the wording of the political declaration, despite her insistence that the deal is the best available.

Then she might try again for Commons endorsement, perhaps in the grim expectation that the financial markets might respond negatively to a first defeat. Thus perhaps - perhaps - spooking MPs on all sides.

Within that admittedly desperate calculation is the prospect that there might - again, might - be some Labour MPs who are prepared to give it one shot at bringing down the government and precipitating a general election: but who might, then, vote for the deal or abstain.

Still in that territory, Mrs May must hope that she can find a form of agreement which placates the DUP - who, at this point, hate the deal but have yet to disavow entirely their confidence and supply arrangement with the PM.

Mind you, it scarcely helped today when she got a little - just a little - muddled over terminology. Nigel Dodds of the DUP asked her about the impact of the deal on "the union." He meant the UK. She answered, initially, as if he meant the "European Union".

To be fair, the word union is used in every one of the 585 pages of the withdrawal agreement to mean the EU. Mrs May might plead that she has been embroiled in Euro-speak. She hastily reverted to the union that is the UK and essayed reassurance.

As she sat down, he could be seen angrily mouthing "words, words". Expect more of them. Many more.

- Published26 November 2018