A bricklayer, a used car salesman and a Lib Dem

- Published

MSPs voted by 92 to 29 to reject the draft withdrawal deal and the notion of a no-deal exit

He said it twice as if for emphasis but, to be frank, my ears had twitched just a fraction at the first mention. Adam Tomkins said that the only realistic Brexit alternative was the prime minister's deal - "or something very close to it".

Eh? Haven't we been told that every word of the withdrawal agreement is nailed down and that the accompanying political declaration is as extensive as it currently can be?

Haven't we been told that the prospect of change was fallacious? That Brussels wouldn't stand it?

And yet here was the Scottish Tories' constitutional spokesperson speculating in today's Holyrood Brexit debate about a potential departure from the deal, albeit one that would be narrowly constrained.

Mr Tomkins was not alone. Earlier, in the Commons, the prime minister was asked to comment on the putative consequences of defeat for her deal next Tuesday, in the meaningful vote.

She said: "I believe that the deal we have negotiated is a good deal. I recognise that concerns have been raised, particularly around the backstop.

"As I said yesterday in my speech during the debate, I am continuing to listen to colleagues on that, and I am considering the way forward."

Which sounded, to this observer, like a search for a further offer which might placate some Tories who have voiced concern as to the impact on the union (the UK union, that is) of distinctive treatment for Northern Ireland, in an effort to avoid a hard border with the Republic.

Adam Tomkins said there was a "clear binary choice" between Mrs May's deal and no deal at all

One suggestion doing the rounds is that the PM might suggest that the Commons would have to affirm, by voting, in advance of the implementation of the backstop.

That would fit with the mood of the House, which is to assert their collective sovereignty. And it would match the prime minister's repeated assurances that the backstop is not inevitable, but a potential choice at some future date.

Which is where we enter the territory of the legal advice, now published at the insistence of MPs. I understand entirely why it has caused a furore. I understand and appreciate why Ian Blackford of the SNP majored on it in questioning the prime minister (why Jeremy Corbyn did not is a question for another day).

However, it does not strike me that the controversy over the legal advice per se materially alters the nature of the real contention surrounding Brexit.

Geoffrey Cox, the attorney general, notes in his written advice that the protocol covering Northern Ireland would "endure indefinitely until a superseding agreement took its place".

Yes, that word "endure" imbues the debate with a sense of intolerable permanence. But, in truth, that was already the concern voiced by Brexiteer critics of the deal, and others. It has been, to be blunt, the very core of their argument, even prior to publication.

They have depicted the UK as being tied into EU rules for ever. The legal advice confirms the existence of that fear.

The SNP's Ian Blackford says the Brexit deal denies Scottish rights

The attorney general goes on to say that this risk of permanence must be weighed "against the political and economic imperative of both sides to reach an agreement". Which has been the PM's point from the outset, that there would be an incentive upon the UK and the EU to bargain.

Mr Cox concludes that the choice is, ultimately, a political one, rather than strictly a legal matter. Which is true inasmuch as EU decisions are always political and diplomatic.

To be absolutely clear, that does not mean that the legal advice is irrelevant. To the contrary, it confirms the fundamental nature of the controversy - and helps explain why the Prime Minister and supportive Tories are seeking further nuances.

But it is confirmatory, rather than, of itself, revelatory.

Parties 'hoodwinked'

The Holyrood debate itself was fractious on occasion. For the Tories, Adam Tomkins said the SNP were seeking to "weaponise" Brexit in pursuit of independence.

He said Labour and the Liberal Democrats had been "hoodwinked" into backing a common motion with the Nationalists (the Greens are also co-signatories but they back the cause of independence).

Mr Tomkins provoked anger from rivals by being reluctant to take interventions in his speech. Tavish Scott of the Liberal Democrats speculated that this was because he did not believe a word of his own comments.

Mr Scott said that the Scottish Tories appeared determined to be the last defenders of the prime minister, while she was deserted by Commons colleagues. The Scottish stance, he said, was "ludicrous".

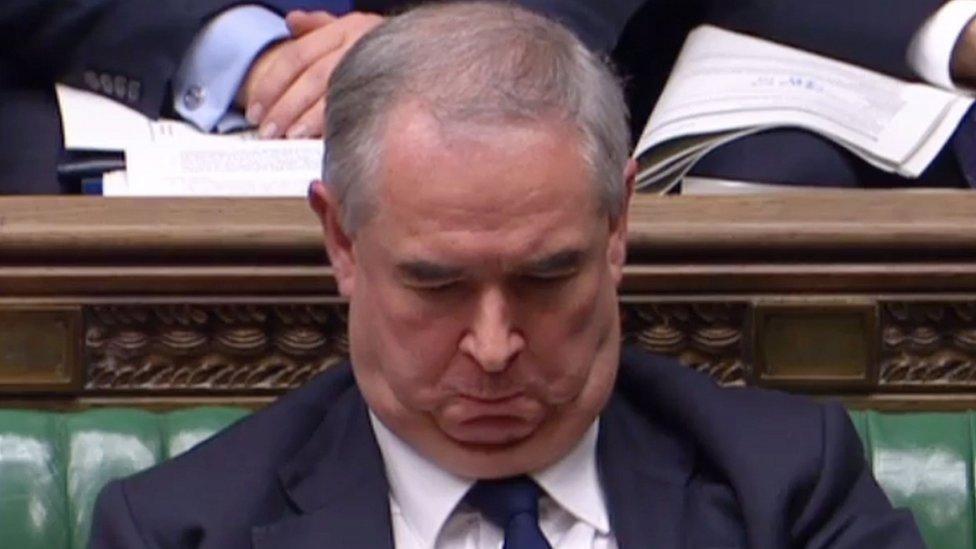

Geoffrey Cox's advice to the government has been published in full after a battle in the Commons

Labour's Neil Findlay chided Mr Tomkins for, as he put it, being "afraid to take an intervention from a bricklayer, a used car salesman...and a Liberal Democrat".

The bricklayer was himself (he later graduated and became a teacher). The Liberal Democrat? Well, take your pick.

And the car salesman? Mr Findlay apparently meant Gil Paterson of the SNP - who rose magisterially, on a point of order, to deny selling cars (the business he founded deals with specialist coatings for the automotive sector and others).

Once again, a Brexit debate threatened to enter the surreal. But there was substance here too. An insistence by the four co-signatories that an alternative could, and must, be found to the PM's deal.

Talks, no doubt, will continue on that front, particularly if the PM loses next Tuesday, as currently expected. But, on the day, there was no single common approach by the Tories' rivals.

The Greens and Liberal Democrats favoured a further referendum, with the objective of reversing Brexit. Labour preferred a general election, with the objective of ousting the Tories.

Neil Findlay said Mr Tomkins was afraid to take interventions from MSPs

The SNP, once again, ranked their preferences. Mike Russell, the Brexit Secretary, began by listing the proclaimed downsides of Brexit and, rather deftly, linking those to constituencies and regions represented by Tories.

He said the number one objective was to remain in the EU; that this could be attained by a further referendum (which some in his party suspect might set a damaging precedent for independence); and that, failing that, negotiations should centre around single market and customs union membership.

He gave less succour to the notion of a general election - other than to say that the SNP would support such a move, if it arose (the broader concern, voiced by the FM and others, is that electoral laws make such an eventuality difficult to attain).

Does today's Holyrood debate - and expected vote against Brexit - matter much? The Tories call it "needless".

But, at the very minimum, it adds to the swelling chorus of voices suggesting that an alternative to the PM's deal must be found. The question is still: what?

- Published5 December 2018