Searching for constitutional precedent

- Published

Theresa May is making a last-ditch bid to get her Brexit deal over the line

As if things weren't bad enough. Not content with battling for Brexit, the prime minister opts to plunge into another constitutional quagmire, that of Scottish and Welsh devolution.

Theresa May is citing precedent. When folk in Scotland and Wales voted for self-government, Westminster didn't seek to thwart their wishes. Did they?

You can see where she's going, can't you? What's good enough for Holyrood and Cardiff Bay is more than suitable for the Brexit project.

Now, of course, one or two mischievous souls - irritating pedants that they are - have suggested that things are not quite so clear as this.

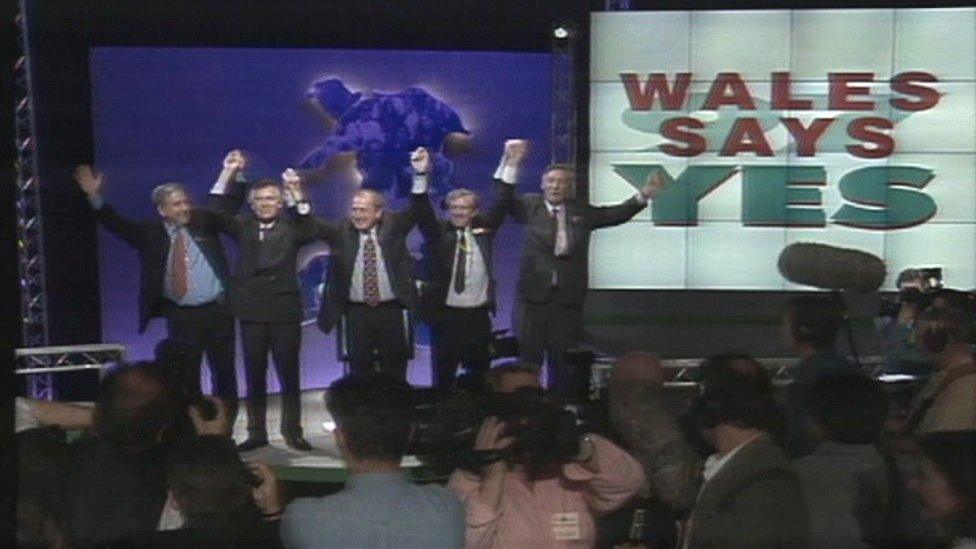

It has even been suggested that May, T. actually voted against the implementation of Welsh devolution - even although it had been endorsed by the people of the Principality.

Albeit by a tiny margin after the final area declared. I know 'cos I was there, to quote the Welsh comic, Max Boyce.

Those with longer memories - yes, including me - might glance back to an earlier referendum, the Scottish devolution plebiscite of 1979.

On that occasion, a majority of those who voted opted for Yes. But the Commons decided against proceeding with a Scottish Assembly, as it was then termed, on the grounds that the pre-set margin of 40 per cent of those entitled to vote had not been attained.

The George Cunningham amendment, if you recall. Or, indeed, if you don't.

Mrs May attempted to use the Welsh devolution referendum as a precedent

So constitutional politics is rarely pure and never simple. In addition to that, there is another key distinction between the current travails and those earlier devolution debates.

With regard to devolution, Westminster remained sovereign. Devolved self-government may have been mandated by plebiscites but, in the case of both Scotland and Wales, it was legislatively granted and sustained by Westminster.

Still is, as we may be finding out with regard to the issue of powers in devolved areas returning from Brussels.

But, in more general terms, this Brexit business is rather different. For the umpteenth time, this is not solely a matter for the House of Commons to decide.

Rather, we are dealing with an international treaty which enables the UK to resile, by agreement, from the international treaties which formulate and comprise the European Union.

Backstairs manoeuvring

What the Commons is doing is ratifying that international treaty. Or not. MPs cannot, by themselves, amend that treaty, however much they may give the impression to the contrary.

Now I worked as a journalist in the Commons for an extended period. Admittedly, that was a wee while back but I still understand the cultural, emotional and historical ties which bind so many members to the place.

I get the concept. Honourable members - and even a few dishonourable ones - tend to see the old chamber, its habits, its appurtenances, through a certain glow.

They may lament or regret its decline in significance. But they are still, many of them, inclined to venerate the role of the lower House, by contrast with the "other place" bedecked in red.

Experienced Parliamentarians are used to the backstairs manoeuvring, to the diplomacy through the usual channels, which facilitates seemingly open democracy. They expect that, eventually, a solution can be found to seemingly pressing problems.

Parliament and those protesting outside remain split over Brexit

To repeat, this is different - and not just because the problem of Brexit is apparently intractable in itself. It is different because this is not the Commons' call. It is not for MPs to decide.

I wrote quite some time back about displacement activity. It is still well in play as we near the self-imposed deadline of March 29, when the UK is scheduled to leave the European Union.

To underline, I make no complaint whatsoever. In the absence of an obvious route to pursue, an institution will naturally revert to contemplating its own procedures. In addition, essaying alternative routes may - I stress, may - generate productive ideas.

So there is talk of a motion of no confidence in the prime minister. To which one might say: and then? The UK is still leaving on March 29.

Perhaps then there should be a motion of no confidence in the UK government as a whole. And then? Remember that date.

How about a general election? Four to five weeks of campaigning. And then?

Or a further referendum on membership of the EU? What if the UK voted, perhaps by an even clearer margin, to Leave? And then?

MPs will vote on Mrs May's deal on Tuesday evening

It seems to me that each of these scenarios - and, I stress again, I make no complaint about their being paraded - point to one conclusion. At least, at this point.

That the UK or, more precisely, our elected representatives in the House of Commons, are not yet ready, it would seem, to sanction that departure from the EU on March 29.

Which would point to the need for the departure date to be delayed. By agreement, of course, with the other partners to the treaty, the EU and its continuing members.

This may be avoided if MPs can be prevailed upon to support Mrs May's package. It would seem, at this stage, that the back-up assurances from the EU fall short of the demands advanced by sceptics, most notably because they do not alter the text of the agreement itself.

Margin of defeat

But, to be clear again, that is because it is not open to MPs to bargain over this matter, to lodge amendments, to have a word with the chief whip. This is a legally binding international treaty, negotiated between the UK's governing executive and the EU.

If Mrs May goes down to a defeat on Tuesday in the Commons, particularly if the defeat is heavy, then our treaty partners, the EU, will be obliged to rethink. Albeit, with ill grace. Will this ever be over, you can hear them asking?

If the defeat is narrow, then Mrs May might conceivably try again, hoping that some Tories and even perhaps some opponents will be deflected by her warning that Brexit might not happen, that the declared will of the UK people will be overturned.

More probably, if the defeat is substantial, then the talk will be of deferring departure, by agreement - and using the time to seek a revised treaty. Again, if our EU partners will consent.

- Published14 January 2019