Of the Bard and Brexit

- Published

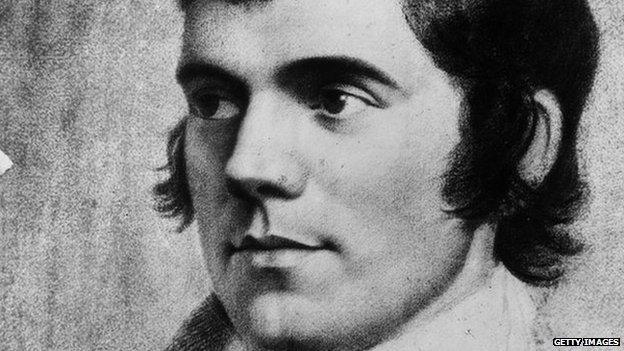

Could the wisdom of Burns help Theresa May out with her Brexit quandries?

There is to be a Burns Supper in Downing Street this evening. Guests apparently include Boyd Tunnock (of teacake fame) and Bertie Armstrong of the Scottish Fishermen's Federation.

An eclectic mix, not least in dietary terms.

One wishes them all happiness with their haggis. It is unlikely, given the times, that the satirised French ragout will also feature on the menu.

But, who knows, perhaps a little of the Bard's wisdom will percolate through the seat of UK governance, with regard to Brexit.

Earlier today the prime minister set out her latest thinking on relations with the European Union. It was eerily similar to her previous thinking.

Theresa May reminded MPs that the UK is due to leave the EU on the 29th of March. Indeed, nae man can tether time or tide.

Some, including Ian Blackford of the SNP, said she was running down the clock and characterised her government as shambolic. He urged her to change tack - and adopt ideas from the opposition. To step aside is human.

Brexit: Theresa May on ‘six key issues’ in EU talks

Mrs May insisted that she remained open to talks across the chamber - and chided Labour's Jeremy Corbyn for refusing dialogue.

What, she pondered, was he worried about? There's nane ever fear'd that the truth should be heard, but they wham the truth would indite.

But Mr Corbyn said she was in "deep denial", refusing to budge while talking of consensus. He said her stubborn approach was unhelpful. Your doctrines I maun blame.

However, the prime minister insisted that Mr Corbyn was being unrealistic. The way to prevent no-deal, which he and Mr Blackford demanded, was to strike a workable deal. Facts, she implied, are chiels that winna ding.

She insisted, further, that she accepted that her deal had been overwhelmingly rejected by the Commons. She was not stubborn, she was not nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

But it remained the prerogative of the government to negotiate on behalf of the entire UK. Despite that, she conceded it would be wise to reach out to other sources of advice, both within and outwith the Commons.

In such a fashion, perhaps consensus might emerge. It might eventually prove that sense and worth, o'er a' the earth, shall bear the gree, an' a' that.

This offer of flexibility was largely derided by opponents who said it clashed with her previous behaviour and her demeanour during the cross-party talks.

However, in addition to that, Mrs May outlined two areas for possible progress. Firstly, an attempt to underline the strongest possible protections on the environment and workers' rights. An outfit of hoddin grey should be no bar to support from the powerful.

Secondly, an effort to construct a deal on Northern Ireland which commands support, not least among her DUP chums.

There must be no return to a hard border on the island of Ireland, to any arrangement which risked a return to violence. That was an outcome, all sides agreed, to be detested, shunn'd by saint and sinner.

It would seem, once more, that Theresa May envisions little in the way of a productive outcome to talks with the Opposition, except on the margins. Her objective, if at all feasible, is to secure concessions on Northern Ireland which might placate her own backbench critics and the DUP.

In this context, she bluntly countered media reports that she was prepared to reopen the Belfast / Good Friday agreement. A chiel may be among us takin' notes, and determined to print. But some reports, she implied, were lies frae end to end.

In essence, she hopes for an about-turn by sufficient of those critics, relying on the flexibility which is at the core of modern politics. The doctrine today that is loyalty sound, tomorrow may bring us a halter.

Within that, Mrs May presumably hopes that the prospect of no-deal may frighten enough MPs into backing her deal, or a slightly revised version. That is why, strategically, she refuses to rule out that option upfront.

She said the only alternatives to no-deal were revoking Article 50 - and thus remaining in the EU - or endorsing an agreed departure.

It was right, she argued, to strike a deal in order to meet the mandate of the UK populace in the EU referendum. Otherwise, the people would understandably conclude that their elected representatives were a parcel o' rogues.

To be clear, her critics disputed this analysis. Alternative approaches, they argued, were available, such as a further referendum. Mrs May seemed prepared to test that scenario in the Commons, offering her opinion that it would not find majority support among MPs.

For now, the prime minister is living proof that the best laid schemes o' mice an' men gang aft agley. But she still nurtures the hope that she may emerge o'er a' the ills of life victorious.

Perhaps, once more, MPs and ministers need, collectively and individually, to look outwards. To consider how their animadversions on each other are viewed by the voters and by Britain's global allies.

O wad some Power the giftie gie usTo see oursels as other see usIt wad frae monie a blunder free usAn foolish notion.

Enjoy your own Burns Supper when it arrives.