Baby death infection source may not be found

- Published

The babies had been in the intensive care unit at the Princess Royal Maternity Hospital

The source of an infection that contributed to the deaths of two premature babies in a hospital intensive care unit may never be known, an NHS chief has said.

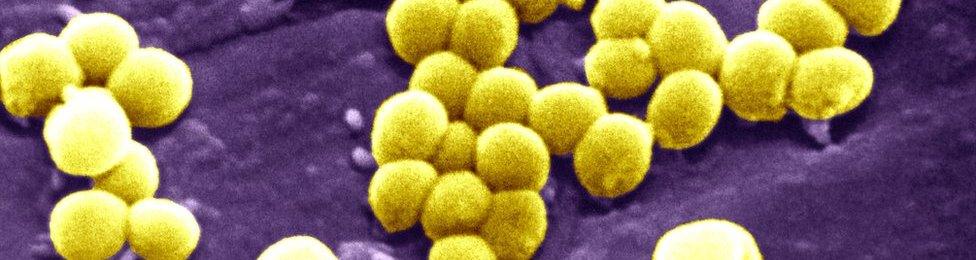

The babies died after contracting the staphylococcus aureus bacterium at the Princess Royal Maternity Hospital.

A third baby in the unit is receiving treatment after also contracting the blood stream infection.

Dr Alan Mathers said medics may never find out what caused the infection.

Dr Mathers, the chief of medicine, women's and children's services at NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, said the two dead infants were born very prematurely and had been among the "most vulnerable patients" in the country.

But he said the third baby who also has the infection is "not giving us any cause for concern at all".

Asked whether it was known how the infection started, he told BBC's Good Morning Scotland programme: "Not yet and it may be that we don't ever get to the root of the problem.

"The issue is that everyone carries bacteria in their skin and are colonised by these things - that is very different from an infection.

"The premature baby has lots of systems that are just not ready for the world, including its immune system, and any breach in the fragility of these babies can lead to bacteria that would otherwise not bother us."

An incident management team was set up on 24 January after the bacterium was detected in the neonatal unit.

Linked cases

Staphylococcus aureus is a bacterium that is found on the skin and in the nasal passage of about one in four people, and only causes infection when it enters the body.

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said in a statement released on Wednesday that the three cases were linked, and that the babies who died had already been "extremely poorly" due to their early births, with infection being "one of a number of contributing causes in both deaths".

The NHS says that intensive care for premature babies in Scotland is the best in the western world

Dr Mathers said because the infants were born so prematurely there had always been "a potentially high chance of a poor outcome".

He added: "As far as neonatal intensive care goes, these are the most vulnerable patients in the NHS, full stop."

The deaths came as prosecutors continue to look at two deaths at Glasgow's Queen Elizabeth University Hospital. A 10-year-old boy and a 73-year-old woman died after contracting the cryptococcus infection.

Jason Leitch, national clinical director at NHS Scotland, insisted that the health service had effective infection control procedures in place - although he stressed that this would be no consolation for those who had lost loved ones.

'These units are safe'

He also said there is "no better place in the western world" for premature babies to be cared for than in Scotland's neonatal units.

Mr Leitch, also speaking to BBC Radio Scotland, said: "These units are safe and if your baby is premature and requires intensive care, this is exactly the place you want your baby to be.

"There is no better place in the western world to have your premature baby looked after than the intensive care units at Scotland."

Cases of the staphylococcus aureus infection in the NHS in Scotland have fallen by 93% in the past 10 years, he added.

Mr Leitch said: "They are rare events, but the fact that they are rare events gives us all the more opportunity to learn from them and aim for zero.

"That would be our hope that Scotland, although leading the world in infection control, would get better still."

Analysis by Lisa Summers, BBC Scotland health correspondent

Staphylococcus Aureus is a widespread bacteria commonly found on the skin of nearly half of the healthy hopulation.

Glasgow's troubled health board is dealing with a third outbreak of infection in a matter of weeks. Four deaths, two hospitals, two entirely separate investigations.

Staphylococcus Aureus is a common bacteria found on the skin.

It is transferred through human contact and can also be airborne through the shedding of skin cells. For most people it stays outside the bloodstream, but it can cause a range of infections if it gets under the skin.

Most of the time you can be treated with antibiotics, but it can be serious. For vulnerable very premature babies whose immune systems have not developed and who need a high level of medical support it can be very dangerous if it gets into the bloodstream.

The 13-bed neonatal unit at the Princess Royal Maternity Hospital will treat extremely ill and extremely young babies. The question for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde here is, has something gone wrong with the strict hygiene protocol at the hospital that has led to a link between the three cases of infection being established?

At the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, the questions are about building design and maintenance.

Cryptococcus, the fungal infection linked to pigeon droppings, somehow got into the ventilation system in a ward or wards where there are already additional measures in place to supposedly protect the air quality. They also need to establish how Mucor, another airborne fungal infection, was transmitted in the hospital.

The health board said that was traced to a water leak. And again, separately, how did bacteria get into the water supply last year, leading to a number of children being treated for infections at the Children's Hospital?

It may be the case that overall infection rates are reducing in Scottish hospitals and it is true that infections are a fact of life in healthcare and can often be routinely dealt with. But there are still plenty of questions for both the health board and the government to answer.