Breakaway MPs and the new 'departurism'

- Published

Heidi Allen (fourth from left), Anna Soubry and Sarah Wollaston appear in Parliament with the Independent Group

Those of us who observe politics are well accustomed to the concept of entryism: the procedure whereby a small but motivated grouping joins a larger party in order to influence and perhaps transform it from within.

Labour experienced this phenomenon in the 1970s and 1980s with Militant. Some senior figures in the party profess to detect a comparable approach now, particularly with regard to the more zealous supporters of Jeremy Corbyn.

Separately, there are complaints that former members of UKIP are joining or rejoining the Conservatives in order to sustain the Tories in opposition to the EU and / or to seek to oust those who take a contrary view.

So far, so familiar. But perhaps we may now also have to get used to the mirror image, to the idea of "departurism".

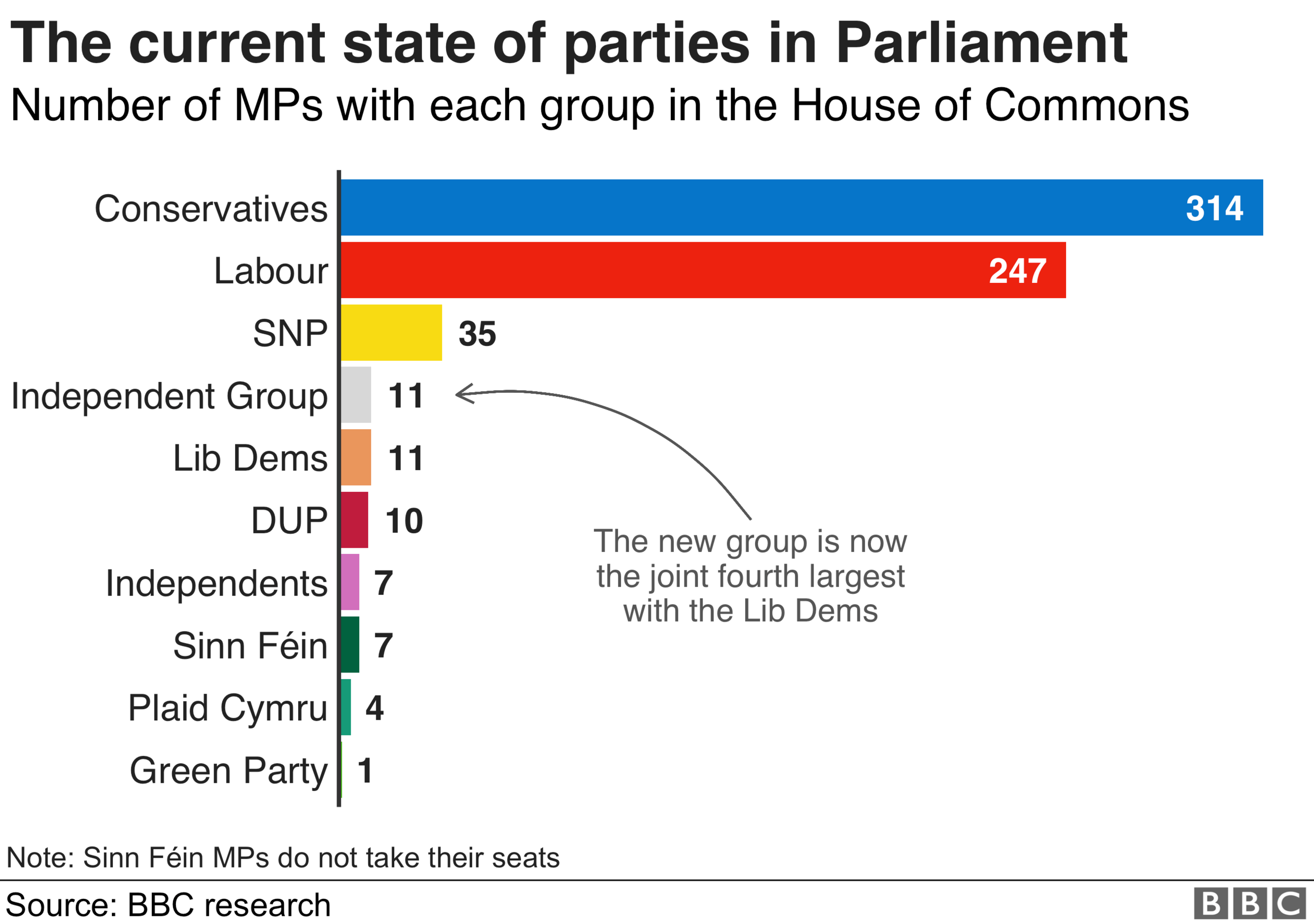

As I write, eight Labour MPs have quit their party to form the "Independent Group". They have now been joined by three Conservatives.

However, rather than forming a new party at this stage, the initial motivation appears to be to influence and transform the pre-existing structure. To reshape their old parties, but from the outside.

In that respect, this development is rather different from the Social Democrat Party in the early 1980s. They swiftly formed a full party structure. They recruited members and fought by-elections, firstly as the SDP and then in alliance with the Liberals.

It is easy now to dismiss the impact of that initiative. Certainly, after early excitement, the overall mould remained stubbornly impervious to fracture.

But it was at least a contribution to political debate which sidestepped the conventional modalities of two party politics.

The current developments, for the moment at least, are a little different. Firstly, it seems to me that the two sectors of the new group have somewhat distinct motivations, despite the appearance of being comparable.

A glib view would have it that both sides are fleeing extremes, of left and right. But I don't think that quite captures the spirit.

Disquiet with the Labour leadership predates the Brexit crisis. The handling of Brexit may have precipitated the final departure for the original seven defectors - but they were keen to stress a range of issues, including anti-Semitism and complaints of internal intolerance.

On the Tory side, the letter to the prime minister similarly lists a range of concerns. But it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the primary concern is Brexit, rather than leadership, discipline or broad policy.

Put succinctly, I do not believe that the Tory defectors would have gone without the impetus of the Brexit chaos. It is conceivable that there would have departures from Labour, Brexit notwithstanding.

Further, I do not believe that the new grouping will easily form the nucleus of a new party. They might, just, manage to coalesce around social policy. But what would be their collective approach to the economy?

The creation of the SDP

Again, when the SDP was formed, it was substantially driven by economic policy, by a reaction to what they saw as overweening dirigisme in financial and business matters. It was possible to form an economic strategy around that fundamental approach.

Such does not even appear to be mentioned at the moment. To be fair, that is because the group do not posit themselves as a party. Rather, they are a potentially powerful protest movement, a new gear in the machine.

It is said further that a few more Tory defections would remove Theresa May's majority. That is strictly true in that she is already dependent upon "confidence and supply" support from the DUP.

I think, however, that is somewhat missing the point. That is an analysis predicated upon rigidity, upon two, solid rival camps sitting two sword lengths apart in the House of Commons.

Brexit has created new rivalries - and new alliances. Those shift and fluctuate according to Brexit progress or stasis.

For example, it is still just conceivable that Mrs May will be able to fashion a compromise, perhaps dependent upon a legal codicil attached to the withdrawal agreement, that may be able to scrape together a majority in the Commons with a fair wind and backing from some Labour MPs.

Equally, there will now be a renewed attempt to fashion support for a further referendum although it would seem to me that is still dependent on a change of tack by the Labour leadership - unless, of course, there are further defections, and many of them.

It is a truism to say that Brexit has left politics febrile and malleable. Truisms are frequently trite. But they are also, just as frequently, true.

- Published20 February 2019

- Published20 February 2019

- Published18 February 2019