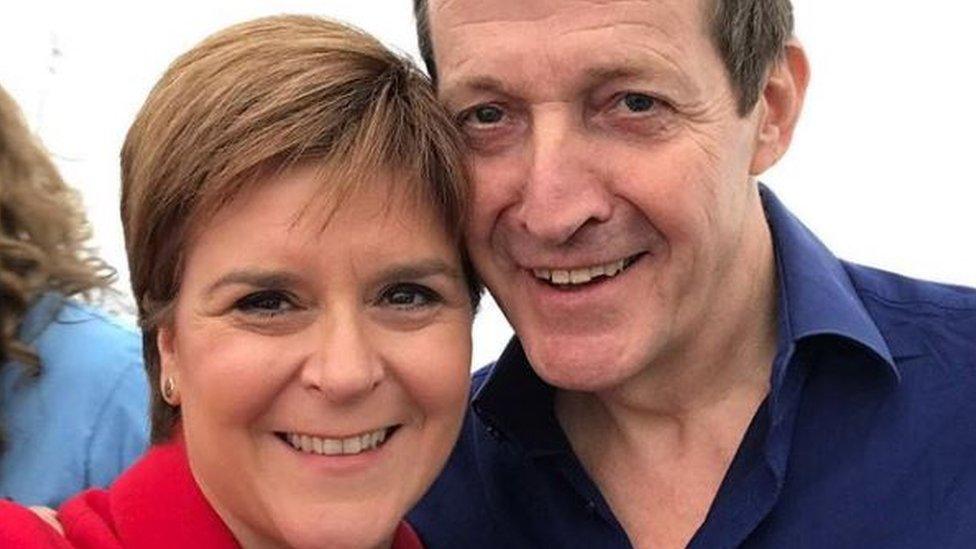

Sturgeon's spindoctor selfie

- Published

Nicola Sturgeon and Alastair Campbell posed for a photo at a march in London

The selfie is now an established facet of contemporary politics, up there with the coffee morning, the constituency surgery and the permanent campaign to win re-election.

Sensible politicians who go walk-about among their adoring voters now build in time for these obligatory random photo-calls.

And so it's twenty minutes for the event itself, another twenty to smile for pests like me with intrusive TV cameras - plus a final twenty to pose, with varying degrees of zeal, for selfies.

Some selfies make news. One thinks of Barack Obama, David Cameron and Denmark's Prime Minister Helle Thorning Schmidt, grinning collegiately, at Nelson Mandela's memorial service.

You remember? The one with Michelle Obama at their side, studiously ignoring their antics and reducing the ambient temperature several degrees.

Now, it seems, Nicola Sturgeon has attracted attention for a posed snap. There she was, at the march for a People's Vote in London, smiling alongside Alastair Campbell, Tony Blair's former spin doctor.

Some with memories of the Iraq War and Mr Campbell's role took exception, it seems. These critics are duly chided by Andrew Wilson in today's National newspaper when he argues that Remain supporters - and, indeed, independence activists - have to learn to make alliances beyond their own demesne.

Intriguingly, the oblique reference to this episode came today from Richard Leonard. He suggested that the FM had found herself in company with some "interesting people".

Mr Leonard, like Mr Campbell, is a member of the Labour Party. Presumably, however, they have rather different perspectives upon Tony Blair and his three election victories.

Richard Leonard might not share Mr Campbell's perspective on recent Labour Party history

Aside from this sklenting reference to the past, Mr Leonard seemed keen to steer clear of the political obsession of the moment, that of Brexit.

Instead, he dealt with the deeply serious topic of child poverty, with the latest figures registering an increase in the scope of deprivation.

Partly, this is because Labour has experienced divisions over Brexit. Partly, it is because child poverty is grimly important.

Partly, it helps drive the narrative that Labour's opposition to the UK Conservative government - and thus demand for a general election - goes deeper than Brexit.

These were valid exchanges, pursued vigorously by Mr Leonard and amplified later by questions from Alison Johnstone of the Greens. The opposition leaders queried, variously, why the Scottish Government had not done more to mitigate benefit cuts.

Why was it taking until 2022 to introduce an income supplement? Why had ministers not backed a £5 hike to child benefit in Scotland?

Nicola Sturgeon took time to give detailed replies. Re the income supplement, it was vital to get the details right - and to ensure that the scheme was affordable. Promises that couldn't be kept helped no-one.

Re child benefit, it had been shown that a flat increase tended, by definition, to help more families who were not in poverty, than those who were. Solutions were being sought.

In any case, she told Mr Leonard, Holyrood still lacked full powers over welfare. Labour, she said, had colluded with the Tories in the independence referendum to sustain that position.

Her version of "interesting people", perhaps.

Jackson Carlaw led on Brexit, defending Theresa May's deal

The earlier exchanges with Jackson Carlaw had also been sharp and satirical. For the Tories, Mr Carlaw lampooned the SNP stance in the Commons' indicative votes.

For months, nay years, they had, he said, urged the retention of a customs union and a single market after Brexit, as a compromise position.

Yet they had abstained in votes on both of these issues in the Commons. Preferring, he said, to foment grievance and division, while pursuing their "obsession" with the prospect of independence.

It was all, he said, "faux outrage". By contrast, one presumes, with the meaningful indignation which consumes the House on other occasions.

Ms Sturgeon was having none of it. There had not been a single motion which met the core SNP demands in an unalloyed fashion. Hence the abstentions.

In any case, the primary objective now was to thwart Brexit altogether. That did not mean that the search for compromise might not resume. Mr Carlaw visibly harrumphed.

Indeed, he contrasted what he plainly regarded as the chicanery of the SNP with the honourable offer of the prime minister to step aside if it would help sway Tory backbenchers to endorse her EU withdrawal deal.

Ms Sturgeon was unimpressed. The resignation offer, she said, lacked detail and didn't seem to have worked.

Which left Theresa May, she said, as the only leader in history to attempt to fall on her sword. And miss.

- Published28 March 2019