How has Scotland changed since the indyref?

- Published

- comments

Five years is a long time in politics

Five years have passed since the Scottish independence referendum. BBC Scotland looks at how the country's politics has changed since then, and how likely we are to do it all again.

Where were you on 18 September, 2014?

If you're a Scot who was over the age of 16, there's an 84.59% chance you were in a polling station at some point, ticking Yes or No on the question of independence.

When those ballot papers were counted up, the No pile was bigger by 55% to 45% - but that was just the beginning of the story.

Wherever you were that day, it's unlikely you would have predicted where we would all be five years later, with the UK seemingly jammed halfway out the exit door of the EU and the question of Scotland's part in it decidedly unresolved.

What has happened during this extraordinary period of political turmoil, and where does it leave us?

Changing faces

Remember them? A lot of big names have bowed out of frontline politics since 2015

The wheels of history were turning within hours of the vote. Alex Salmond, Scotland's longest serving first minister and SNP leader, announced he was stepping down.

He was far from the last - if a year is a long time in politics, five is apparently a lifetime. The cast of characters at the top of the game has changed almost completely.

This is particularly true on what was supposedly the winning side - David Cameron, Alastair Darling, Nick Clegg, Ed Miliband, Jim Murphy, Kezia Dugdale and now even Ruth Davidson have all bowed out of frontline politics.

Mr Salmond's replacement was at least a familiar face - his deputy Nicola Sturgeon, who embarked on a sold-out stadium tour before returning the SNP to government in the 2016 Holyrood election.

Other members of the Yes campaign have gone on to secure prominent positions - like Mhairi Black taking Douglas Alexander's Westminster seat, or Jeane Freeman winning one at Holyrood and rising to the post of health secretary.

Electoral rollercoaster

Somehow, the issue of Scottish independence has boosted the fortunes of both the party most strongly in favour of it - the SNP - and the one most staunchly opposed to it - the Conservatives.

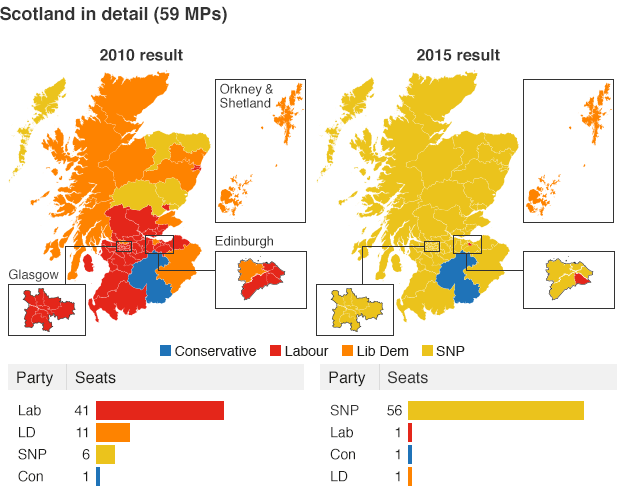

The SNP were the first to have a surge post-indyref, recruiting tens of thousands of new members under Ms Sturgeon and going on to score a stunning landslide in the following year's general election.

It's hard to understate just how massive the 2015 election result was. The SNP gained almost a million votes and 50 constituencies, leaping from third place in Scotland in 2010 to holding all but three seats.

The SNP almost wiped their rivals off the map entirely in 2015

For the losers, the headline was Labour's near wipeout, losing 40 seats. But the Lib Dems, fresh from five years of coalition with the Tories, also saw their vote utterly collapse, losing more than half their support and 10 seats.

All of a sudden, the SNP were the third party at Westminster - and by a comfortable margin.

Some of the new MPs didn't have a lot of time to settle in, though, because another election was coming down the tracks only two years later. This time, the pendulum swung in a different direction.

The Scottish Conservatives were the ones cashing in on the constitutional question in 2017, draping themselves in the Union flag as the "no to indyref2" party on their way to gaining 12 seats in the snap election.

The SNP lost almost half a million votes as the electoral tide went out again, shedding 21 seats - but remained in position as the dominant force in Scottish politics with the majority of the country's Westminster seats.

Labour and the Lib Dems had mini-recoveries of their own, but it was the two parties camped most vocally on either side of the question of independence who were streets ahead, combining to take almost two thirds of the votes cast in Scotland.

The electoral shifts inside the span of a few years have been dizzying in some areas. The swingometer hasn't just broken, it's melted.

There were seats comfortably held by Labour or the Lib Dems in 2010, which yielded double-digit majorities for the SNP in 2015, but then turned blue for the Tories in 2017.

Who might win them in the election broadly expected for later in 2019?

That other constitutional issue

Nicola Sturgeon has been as involved in the debate over Brexit as she is in the independence one

The reason we had a snap election in 2017 and seem poised to have another is because the electorate were asked another binary constitutional question - about membership of the European Union.

In that 2016 contest, 62% of voters in Scotland backed Remain - while 52% across the UK as a whole voted to Leave.

Politicians have spent the three and a half years since then trying to work out exactly what "leave" means, and how to go about doing it.

Theresa May - who succeeded David Cameron as prime minister shortly after the referendum - tried a snap election to boost her majority, and ended up wiping it out. After failing to get a deal she negotiated with European leaders past the Commons, she handed over to Boris Johnson, who is locked in a struggle of his own with MPs.

All the while, the disparity between the vote in Scotland and the vote UK-wide has gnawed away, ever-present in the local debate. Unsurprisingly, the pro-independence parties see it as a decisive point in their favour; equally unsurprisingly, the unionist parties are unconvinced.

As we can see in the wild swings in the various elections held since - including a European election which saw the Brexit Party finish second in Scotland and Labour fifth - what the electorate make of it all is less clear.

Combined, the two referendums seem to have raised constitutional questions which are, as of yet, unresolved.

Play it again?

The issue of independence hasn't exactly gone away in the last five years

You will probably have noticed that the issue of independence hasn't exactly gone away over the last five years. Each of the political parties have marked the anniversary by restating arguments which have by now become extremely familiar.

So...are we going to have another referendum?

As with everything in politics, it's uncertain - and depends on who you ask.

The Scottish government are certainly pushing for a new vote, in the second half of 2020, and have drawn up legislation which might pave the way for one.

But Ms Sturgeon insists she wants to do a deal with the UK government first - the model followed in 2014 - to make sure everything is nice and legal. And given the UK government has spent the last two years saying no, that could prove a considerable sticking point.

Could the upcoming general election prove pivotal?

Well, whoever ends up in Downing Street - Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbyn - it seems like they would be far more focused on Brexit in the first instance.

Mr Johnson is staunchly against independence, and Mr Corbyn wants to hold a fresh referendum on EU membership. While the SNP would welcome one of those, it would presumably impact on the timetable for indyref2, were the new PM to agree to it.

So the 2021 Holyrood election could end up being another contest which becomes a battle for a mandate, for or against indyref2.

The question of Scotland's place in the UK hasn't gone away over the past five years, and it doesn't seem like it's going to be going away any time soon.

- Published19 September 2014

- Published8 May 2015

- Published9 June 2017

- Published24 June 2016