Political chess over the indyref2 question

- Published

Richard Leonard and Nicola Sturgeon clashed over the question of the indyref2 question

For some reason, probably the proven intellect of its denizens, Dundee has long harboured a legion of enthusiasts for the game of chess. In my younger years, I was one of them.

Few things cheered me more as a youth than a king's pawn opening or a Sicilian defence. OK, maybe football had the edge. And hockey. And music. And…

Fine, right, starting again. I was fairly keen on chess among many other things, finding it challenging and soothing in equal measure.

First rule of chess? Learn to think several moves ahead. If you bung your bishop into an attacking position, what is your opponent going to do with their rook?

I'm not sure if Richard Leonard is a chess man. He's got the intellect, for certain. But has he got the guile, the rat-like cunning required to succeed?

Today, for example, he asked Nicola Sturgeon, in an indignant tone, about the question which might be used in any future independence question.

Ms Sturgeon rose, with a silky smile, to seize the opportunity thus offered. She could spot the gap in Mr Leonard's pawn structure and she didn't miss.

Her opening gambit was to thank him, with effusive satire, for conceding that indyref2 was now quite definitely on the table.

Cue protests from Mr Leonard. No, no, Scotland had made its choice five years ago.

In which case, said the FM, was it not passing strange to be demanding details of the question for a referendum the Labour leader intended to thwart?

She went further. How could it be consistent for Mr Leonard to oppose indyref2 (on the basis that Scotland had rejected independence) when simultaneously demanding a second ballot on Brexit (where the UK which he espoused had demanded to leave the EU)?

And further still. Not content with seeking to block indyref2, she said it now appeared that supporters of the Union were trying to "rig the question".

Check, if not mate.

But Mr Leonard was far from finished. He pointed out, accurately, that the Electoral Commission had insisted that it must be allowed to test the question in any further plebiscite on independence. He pointed out, equally accurately, that ministers say that isn't necessary, that the question is clear, comprehensible and well-established.

Challenging the Commission, he argued, was tantamount to ballot rigging.

Hands up those who remember the wording of the question in 2014. No, not you, first minister. Nor you, Mr Russell. Hands down.

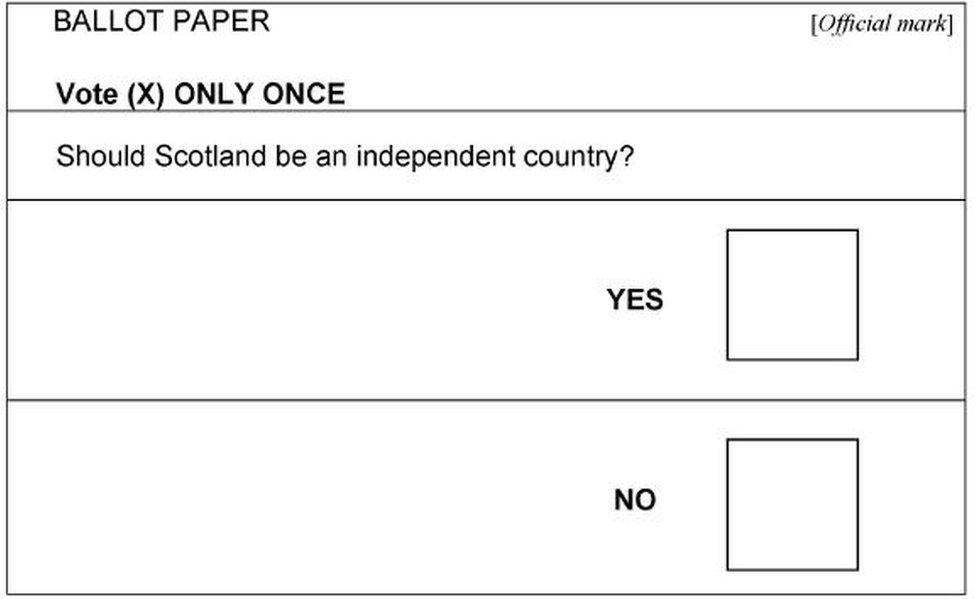

Anyone? Yes, of course, it was: "Should Scotland be an independent country?" This was tested to exhaustion in focus groups and in other ways by the Electoral Commission.

Eventually, they concluded that it was simple, that it more than got the gist of the issue and, most importantly, that the electorate as a whole well understood the nature of the choice, and its consequences.

Independence supporters have been urging Nicola Sturgeon to call a new vote

Since then, some have suggested alternatives. Perhaps a Leave and Remain question, as per the Brexit referendum.

Now, the wording really matters. You cannot have language that encourages a particular outcome, while discouraging the alternative.

Certainly, Nationalists might prefer: "Do you want your proud nation of Scotland to have the same rights as any other country and to prosper in a new era of freedom?"

Unionists might opt for: "Do you want to impoverish Scotland and to send her back to the pre-Union Dark Ages?"

Neutrality is sought. The Scottish government's case is that the question was thoroughly tested prior to 2014 - and that a further round of checks is otiose.

The Electoral Commission says that, despite that argument, they must reserve the right to check the question again, to determine whether it is still salient and right.

Some on the unionist side suspect that ministers are standing firm on this in order to claim that they are making a major concession if and when they ultimately change tack and agree, harrumphing, that the Electoral Commission will, after all, have their day.

The gambit deceptive, if you like. To be clear, ministers are adamant that such is not their intention. They do not believe that the time or expense of a retest is warranted or justified.

Jackson Carlaw currently leads the Scottish Tories, after Ruth Davidson retreated to the back benches

These exchanges with the Labour leader were pretty robust. Nothing by comparison with the Commons, admittedly, but lively.

In contrast, the discourse between Ms Sturgeon and Jackson Carlaw of the Tories was grave and constrained.

Which is entirely apt given that the topic was the sentencing of serious criminals. Mr Carlaw argued that, in certain circumstances, a life sentence should mean just that, lifetime incarceration.

Rather effectively, he bolstered his case with heart-rending examples, drawn from victims of crime. This is, of course, the most difficult type of question for the first minister to answer.

It is one thing to argue, in generic terms, about crime and punishment. It is quite another to respond when the question is founded upon an individual and tragic case.

Ms Sturgeon proceeded carefully and cautiously. She empathised with those families who had fallen victim to crime.

She noted that it is presently feasible for a sentence to be, in effect, equivalent to a whole life term. That is, presumably, dependent upon the age of the offender and the length of the punishment period handed down.

She argued further that sentencing discretion must be left with the courts. Mr Carlaw persisted. Specific whole life terms, he argued, would add to the armoury of those courts. Once again, Ms Sturgeon promised to listen and to heed the views of victims, while noting that there were many experts who argued against whole life.

A valid, valuable exchange which did its job of obliging the first minister to defend her government's stance in Parliament.

Alison Johnstone's Greens want more action from the government to meet its green targets

There was slightly more edge in the exchanges with Alison Johnstone of the Greens. Ms Johnstone's party opted to abstain when MSPs voted yesterday to strengthen Scotland's targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

The aim now is to have all emissions offset by 2045, five years ahead of the UK target date.

Ms Johnstone doubted whether the target would be met. In pursuit of that, she listed other areas, such as hospital waiting, where government endeavours had fallen somewhat short.

As is her wont with the Greens, Nicola Sturgeon blended emollience with steel. She shared their verdant concern for the planet. But she could not understand, in all honesty, how they ended up abstaining.

Smiling benignly, Ms Johnstone said she believed the SG approach lacked ambition - and they could not afford it support, as a party.

Again, though, moderate and relatively constrained. The linguistic clamps were lifted, however, in a brief but tempestuous exchange over - what else - Brexit.

For the Tories, Graham Simpson queried how much cash Scottish councils had received out of the Treasury dosh handed down to Scottish ministers to alleviate the impact of Brexit.

Mr Simpson concluded his challenge by sententiously pronouncing that there were just 35 days to Brexit. He then subsided, content that his duty was done.

Ms Sturgeon rose in cold, evident fury. Had she heard aright? Was this a Tory MSP - a Tory - asking her about efforts to contain the damage which might arise from Brexit?

The cash was only needed at all because the Tories had embarked upon Brexit. Otherwise, not a single penny would be required.

And, more generally, where are we with Brexit, then? Stalemate, friends, stalemate.

- Published23 September 2019