What might UK spending pledges mean for Scotland?

- Published

With an election looming, political parties have been setting out a range of competing spending plans. But given many of them fall in devolved areas, how do these pledges affect Scotland?

A polling date might not have been set yet, but be in no doubt that the UK is in the depths of an election campaign. To this end, politicians have been unveiling a range of new policies. Expensive new policies.

What is often obscured is the fact that many of these plans cut across areas like health and education, and as a result won't directly apply in Scotland.

Instead, if these promises are ever acted upon the Scottish government will get an extra chunk of funding in its budget. But how is this worked out, and when does it apply?

Extra cash

To take a contemporary example, let's look at health. Politicians invariably see showering cash on beloved institutions like the NHS as a guaranteed vote-winner - hence a certain bus-based slogan during the EU referendum, and the latest promise of infrastructure funding for hospitals.

But in Scotland, health policy is one for Holyrood, so this funding boost doesn't apply north of the border. The UK health secretary can't go around making decisions about what happens in Scottish hospitals, because there's a Scottish health secretary to do that.

But under the "fiscal framework" deal underpinning devolved finances, the Scottish taxpayer - who after all is chipping in for the UK-wide budget - doesn't lose out because of this.

Instead, every time extra money is spent on services south of the border, like health, the Scottish government is given a certain lump sum of cash to spend on whatever they please.

That last part is an important principle. Scottish ministers aren't tied to spending money on one area just because it's a priority for their UK counterparts. However, in practice there is often political pressure from opponents to ring-fence such cash, as recently happened with extra NHS funding announced by Theresa May.

These injections of extra cash are known as "Barnett consequentials", after the Barnett formula which is used to calculate the overall level of devolved finances.

How much?

The Barnett formula helps to determine how big a slice of the UK's public spending budget each nation gets

Barnett consequentials are generally worked out at the time of a UK spending review or fiscal statement, at a point when departmental budgets are set at Westminster.

This means when policy pledges are made during a campaign or conference, it can be slightly tricky to work out exactly how much extra funding the Scottish government will be due.

This isn't helped by the politicking and "spin" that goes on around such things - politicians of all stripes enjoy announcing spending plans so much that they often announce the same funds repeatedly. For example the £200m pledged to a "national bus strategy" at the Tory conference had actually already been announced, in the last spending review. It was the details that were new, not the money itself.

And that's before you get into the realms of;

announcements paid for with extra taxation

money shuffled around from elsewhere in the same department,

or funding that's split over a number of years (and thus budgets).

But for the sake of argument, let's focus on truly "new money".

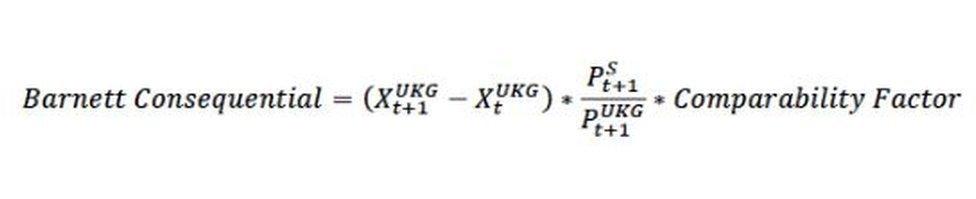

To get technical, the calculation is based on the change to the relevant UK government department's budget, multiplied by a "comparability percentage". Put simply, this is the extent to which that department's services apply in Scotland - the more devolved it is, the higher the percentage. This is then multiplied by Scotland's share of the UK population.

Easy, right?

As an example, let's look at education funding. Because education is completely devolved, it has a "comparability factor" of 100%. And as Scotland's share of the population compared to England is 9.7%, Barnett consequentials stemming from extra spending in this field come out at 9.7% of the total.

So, for every £100 extra the UK government spends on the education department south of the border, the Scottish government gets £9.70 in its next block grant.

That's a clear-cut example because education is 100% devolved. It gets more difficult when you break down the various different roles of big departments - for example the Home Office, where policing is one for Holyrood, but immigration is one for Westminster.

Somehow, it's been calculated that the overall comparability percentage of that department is 91.7%. So - very broadly - if the Home Office gets an extra £100 in its departmental budget, £8.89 would head north in Barnett consequentials.

When does this happen?

Spending pledges from Sajid Javid can provide extra cash for his Scottish counterpart Derek Mackay

In the most recent UK government spending review, external, Chancellor Sajid Javid announced increases in spending on schools, social care and the police, all of which prompted Barnett consequentials totalling more than £1bn, external.

But what about the pre-election pledges which parties have been making at their conferences?

The headline pledge from the Conservative conference has been the aforementioned cash for hospitals in England. According to the comparability factors, health is 99.4% devolved, so this will manifest north of the border as extra money for the Scottish government. Exactly how much and when it might appear remains unclear.

There has also been much talk of transport infrastructure spending, and money for bus services - but again transport is almost entirely devolved, so will result in a lump sum being paid rather than the specific things that UK ministers have been announcing.

Away from spending, Scotland also has its own income tax system, so the suggestion that Mr Javid might be planning tax cuts also doesn't apply - all that would do is widen the existing gap between the regimes north and south of the border.

From Labour's recent conference, the promise to scrap Universal Credit would apply north of the border, as the benefit is reserved. So would the party's plans for the immigration system, which is also controlled from Westminster.

The pledge of free personal care for the elderly would not apply, given that it's devolved and indeed has already been implemented in Scotland. However, if it takes the form of a boost to the social care budget, that would result in Barnett consequentials.

Of course, the UK conferences have for the most part been focused on the issue of Brexit - which, much to the Scottish government's annoyance, certainly does apply UK-wide.