Looking for a Brexit compromise?

- Published

Boris Johnson has made no secret of his biggest goal - to "get Brexit done"

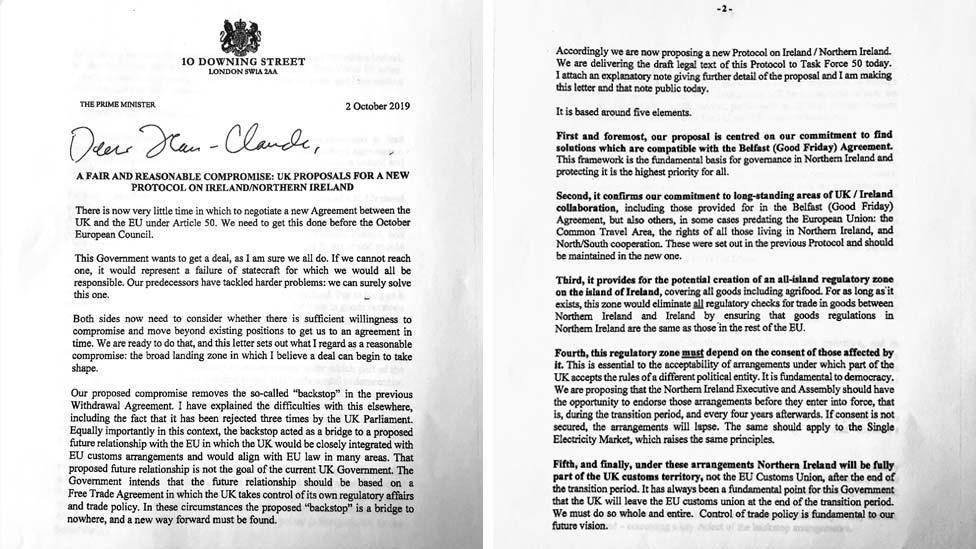

And so we have the proposals from the UK government anent a possible Brexit deal with the European Union. At the Tory conference, the prime minister provided a trail for publication, billing them as a "compromise".

In essence, the package consists of an all-Ireland regulatory zone for trade in goods, including farm produce. That is, until a free trade agreement is reached.

The detail you may examine elsewhere. But perhaps a few underpinning points stand out.

Firstly, the suggested compromise relies upon urging all sides to scale down their expectations and their concerns. In short, to cool it.

That features in the opening remarks where, referring to the Withdrawal Agreement as a whole, the prime minister notes: "Our predecessors have tackled harder problems: we can surely solve this one."

Today's document also notes that goods trade between NI and Ireland makes up just one per cent of the comparable UK-EU market. In short, the immediate problem ranks numerically below the issue of wider trade.

Such an appeal is consistent with the UK's approach to Northern Ireland diplomacy down the years which has been to seek to counter dramatic rhetoric with understatement, where necessary.

Secondly, the package still features distinctive treatment for Northern Ireland. Distinctive, that is, from the remainder of the UK.

Mr Johnson stresses the absence of the backstop which he and his colleagues so loathed. And the objective would be, ultimately, for the UK to leave "whole and entire" from the EU, with a common customs arrangement across Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

But still the proposed interim solution involves distinctive treatment in respect of goods for Northern Ireland, keeping regulations on the island of Ireland in line for that transitional period with the EU.

That distinctive treatment may worry some.

Mr Johnson has written to the European Commission president about his proposals

Thirdly, the package contains an overt offer to Unionism of the Northern Ireland variety. It stresses the importance of consent, translating that into a promise that the Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly (currently in suspension) must have oversight, initially and every four years.

That principle of consent, of course, again matches the UK's consistent approach to Northern Ireland which is to recognise the rights of each community, including the Protestant Unionist plurality.

Fourthly, the attempt to assuage concern in Northern Ireland is translated further. Into cash. More, it would appear, than was previously provided in order to persuade the DUP to back Theresa May's administration.

This time around, Boris Johnson is talking about a "New Deal for Northern Ireland, with appropriate commitments to help boost economic growth".

There would be support to enhance competitiveness and backing for infrastructure projects, notably those with a cross-border focus.

The original cash deal with the DUP prompted disquiet elsewhere, notably in Scotland. Expect the same again.

Proposals for the future of the border on the island of Ireland are under the microscope

Will Mr Johnson get this through? The early signs are not entirely propitious, with a cool initial response from the EU and the Republic of Ireland.

But these plans could at least form the basis for further and possibly final negotiations, designed to achieve agreement in a fortnight's team at an EU summit.

There will be considerable pressure upon the EU to strike a deal, not least from countries whose industries trade substantially with the UK. Call it the Mercedes Tendency. Or the Fiat Force.

Might individual EU leaders - rather than the central institutions - be constrained to strike a bargain? In essence, to overlook - or understate - the immediate problems in search of a longer term settlement.

How about in the Commons? Mr Johnson argued, in essence, that folk are utterly sick of Brexit and want it done. If that is true, might it influence some - on his own side, on the Labour benches - to back a deal, just to be done with it all?

It appears evident that Mr Johnson is now intent on a deal, while continuing to insist in his conference speech that the only alternative is departure on a no-deal basis.

Once again, though, in his speech, he simply sidestepped the issue of how he might get round the Commons requirement that no-deal is to be ruled out by a letter from the PM to the EU.

'Dead in a ditch'?

How might he obviate that? He might seek to ignore it, risking a further court challenge which he would probably lose.

Sir John Major warned that the PM might lodge an Order in Council setting aside the implications of the Benn Act (ruling out No Deal) until after the UK has left. That seems unlikely - and also vulnerable to legal challenge.

So might he obey the letter of the law and send a letter to the EU, suggesting an extension of UK membership? Might he do that in the expectation - perhaps a negotiated expectation - that the request would be refused? By the institutions or at the behest of a major member state?

Perhaps. There is of course another option. Boris Johnson might resign, standing by his statement that he would rather "die in a ditch" than approach the EU for another extension.

In UK Brexit discourse, rhetoric is always to the max.

- Published2 October 2019

- Published2 October 2019