A great deal (or not) to think about

- Published

Boris Johnson announced the deal with European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker

Firstly, congratulations where they are due. Boris Johnson has achieved what many said was impossible (although not this column). He has struck a revised deal with the European Union anent the UK's departure.

In doing so, he has countered claims in many quarters (although not here) that his endeavours were calculated and designed to fail.

Further, he has undermined the assertion (widely heard, although not….ok, you get the concept by now) that the EU would never under any circumstances reopen the Withdrawal Agreement reached with Theresa May.

He did so by astutely pursuing a bilateral deal with the Republic of Ireland, thus encouraging the remainder of the EU to follow suit.

By now, the EU 27 are desperate for a settlement, eager for a deal which was designed to foster rather than thwart trade, inasmuch as such a concept is feasible in the new set-up.

Your verdict upon that relates to your broader verdict upon Brexit.

The EU 27 wanted that deal because of what you might call the Mercedes Momentum or the Fiat Factor. In short, the desire of European industry and business to continue trading as easily as possible with the UK.

Plus the understandable desire to be shot of the whole affair.

Witness now the intriguing set of responses to Mr Johnson's deal. Each of those various responses is predicated upon the underlying nature of the agreement, in addition to its overt substance.

The DUP, upon whom Mrs May depended for a confidence and supply deal, are decidedly unhappy. (Confidence? Remember that? Supply? That is, a majority Commons vote upon budgetary matters. For now, dream on.)

That DUP discontent is to be expected. By definition, an agreement which placates the Republic of Ireland is unlikely to suit the Democratic Unionist Party.

In essence, Mr Johnson has concluded that he simply could not provide everything which the DUP required while still reaching a deal with the member states of the EU, including Ireland.

DUP leader Arlene Foster has so far said her party could not back the deal

Hence an agreement which, in practice, provides for distinctive treatment of Northern Ireland by establishing a monitored regulatory and customs border in the Irish Sea. To be clear, however, NI would be within the customs zone of the UK and would leave the EU along with the UK.

Now, the DUP have not been averse to distinctive treatment in the past. In return for providing Mrs May with confidence and supply, they received substantial investment for Northern Ireland: investment which was not made comparably available to Scotland or elsewhere.

But this is different - and one grasps the difference. This is treating Northern Ireland in a distinctive constitutional fashion - and, what is more, arguably aligning it more closely with the EU via the Republic of Ireland than the remainder of the UK.

Again, one might say that such a tendency is already present in the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement which placed devolution within the wider context of north/south co-operation on the island of Ireland.

But this, again, is different. It plays to the underlying anxiety of Unionists in Northern Ireland - which is that closer co-operation might lead to the elision of the border altogether.

Study the text

I get the concept. Boris Johnson undoubtedly gets the concept. But he has chosen, deliberately, to suit the wider interests of the UK, as he perceives them.

Prior to this, the most zealous Brexiteers in Tory ranks, the European Research Group, indicated that they would take their lead on sundry agreements and sundry Commons votes from the DUP. If they were happy, etc.

But what is this? Now, various members of the ERG say they might well vote for the Johnson deal, despite the DUP anger. Others still say they will study the text.

How can this be? Partly, it is a desire for a deal before the entire project risks unravelling in either a general Election or a second EU referendum or both.

But, it is also because, for the Tory Right, this was never really about Northern Ireland.

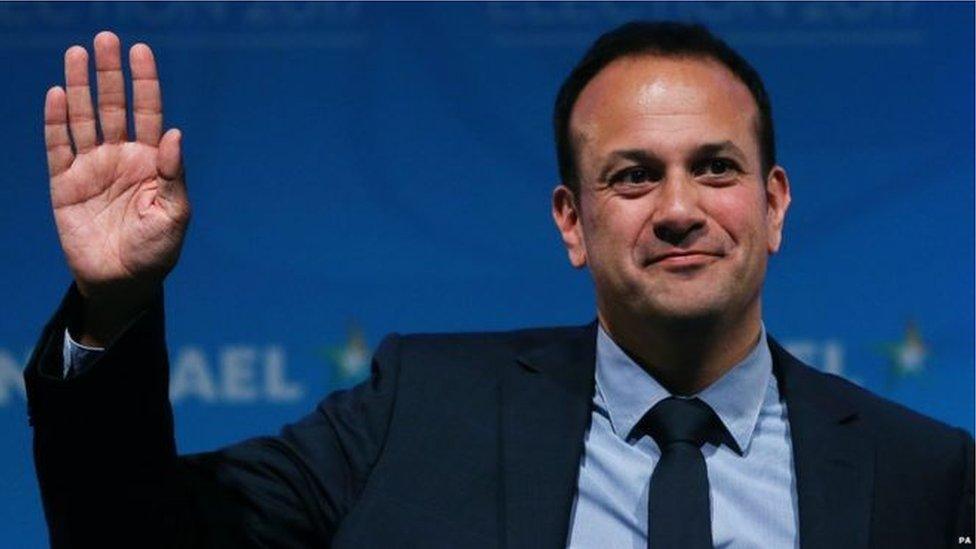

Irish leader Leo Varadkar had a series of bilateral meetings and conversations with Boris Johnson

Yes, they excoriated the NI backstop. But that was largely because it contained the prospect that the entire UK would be kept within the EU customs union indefinitely, pending a wider trade deal.

That would have prevented the UK from striking new global trade arrangements because such individual negotiations are barred within the customs union.

Now the backstop is gone. It has been replaced by a new front page or advance guard, call it what you will. That aims to sort Ireland from the outset, with the proviso that the agreement is subject to regular review by Stormont (when reconvened.)

Even that review is potentially to be granted by a simple majority rather than full cross-community support, as is standard in NI (although that option is also present.)

Cue, again, decided disquiet from the DUP - whose veto just vanished.

For the Tory Right, though, for the Brexiteers, there is another prize. The draft future relationship now disavows the prospect that the UK might, in practice, maintain regulatory alignment with the continuing EU.

Different rules and regulations

It still might - but the default position has gone. This opens the prospect, dear to Brexiteers, that the UK might pursue trade deals under different rules and regulations, distinct from those of the EU 27.

That, for them, is why the backstop had to go. It was a potential block in the path of UK flexibility. And UK flexibility was one of the main reasons they sought Brexit in the very first place.

So where now? The SNP points out that the deal brings about the prospect of the hardest Brexit thus far on offer - and that Scotland, uniquely among the territories of the UK, gets nothing which matches the voting pattern of her people.

They say that Scotland voted by a substantial margin to remain in the European Union - yet is to be withdrawn from the EU, the customs union and the single market.

By contrast, they say that England voted to Leave, Wales voted to Leave - and the Northern Ireland Assembly has been granted a review function. Tories tend to respond by saying that Scotland voted to stay in the UK in 2014 and thus falls under the ambit of a UK decision on Brexit.

Nicola Sturgeon has said the deal would put Northern Ireland at a competitive advantage over Scotland

Now, the focus turns to the vote in the Commons. Already, the recriminations have begun. The SNP says Labour will "never be forgiven" if their MPs help to facilitate what the Nationalists call a "Tory Brexit".

Why might some Labour MPs, in England, vote for Mr Johnson's deal? Two reasons. Firstly, the scunner factor.

Like many voters, they may find the continuing discourse over Brexit to be weary, stale, flat and unprofitable. They may want it simply to end. That factor may also influence some wavering Tories.

But, for Labour MPs, there is an additional element. A fair number represent constituencies which voted to leave the EU. They may find it very hard to vote to thwart the fulfilment of that verdict. I suspect that Jeremy Corbyn fully understands that motivation.

In Scotland, of course, gaming such matters produces rather different considerations. The SNP is the largest party here - and advocates Remain (while also including Leave supporters among its vote.)

Pressure on Labour

The Liberal Democrats also back Remain - either through a referendum, like the SNP, or (somewhat boldly) through reversing Brexit altogether if there is a majority LibDem UK government.

All of that adds to the pressure upon Labour in Scotland. And, of course, the Tories.

The Scottish Conservative leadership has advocated Remain and, in particular, talked up at various points the advantages of the EU single market.

Ruth Davidson didn't just follow that line. She played a prominent role in leading it, during the 2016 referendum.

Now, she has stepped down, largely for family reasons but also because she could not credibly advocate the new course being pursued by Boris Johnson.

In her place, for now, Jackson Carlaw has dropped any lingering adherence to the EU single market and urged the party to back the PM. Scots Tory MPs seem inclined to agree.

In practice, given the momentum behind Boris Johnson, Mr Carlaw had little realistic option while his Scottish Tories remain thirled to the GB party and the Commons Conservative Whip. (Some say that should change - but that is for another day.)

Jackson Carlaw has urged the Scottish Concervatives to back the PM

Will they then face a backlash in Scotland if Mr Johnson gets his deal through? They may indeed. As may Labour. Although that may be mitigated somewhat by the scunner factor - the desire to be done with this and to move on - and by calculations as to the relative salience of Brexit, as against other issues such as the economy and independence.

Can Mr Johnson, even at this stage, get the DUP on board? As I write, that seems all but impossible.

He could try offering further financial inducements to Northern Ireland. Indeed, there was talk at an earlier stage of a New Deal for NI. Echoes of Roosevelt, suggestions of hard cash.

Such manoeuvres have been a tactic of the British state since Nye Bevan bought off opposition to the NHS from some doctors by "stuffing their mouths with gold". Actually, that tactic was pursued previously, then and since, rather assiduously on occasion.

But this is different. This is not a here today and gone tomorrow confidence and supply agreement. This is fundamental. This is about the very future of Northern Ireland. This is about the founding principles of Ulster Unionism, its raison d'être.

Arguably, no funding package can compensate for that. Mr Johnson may still hope to assuage DUP concerns, to persuade them that the Union they cherish, that of the UK, is not in jeopardy because of a deal with another Union, that of the EU.

He may then offer to underpin such assurances with cash. Right now, that does not look like working.

Can he do it?

Which leaves Mr Johnson dependent on corralling: his own Conservative MPs; the departed ex-Tories (those who left and those he sacked); and sufficient Labour MPs from Leave constituencies.

Can he do it? Yes he can. Will he do it? By no means certain.

If he fails, presumably he writes a letter to the EU requesting an extension of the Brexit timetable - with, equally presumably, a broad hint that he rather hopes they reject his request.

What if, as seems certain, this all eventually results in an early UK general election? Mr Johnson will hope to shepherd Leave and loyal Tory votes into his corner. He has much more clout in doing so, now that he has a specific agreement, ratified by the EU.

By contrast, I have long felt that a Tory pitch for support, based on People v Parliament, was less likely to succeed in the absence of a negotiated deal on the table in advance.

In Scotland, the SNP will seek to blend Remain voters with their customary support, adding in those who might feel Scotland has been short-changed. The signs are they may be relatively successful in that quest.

Throughout the UK, the Liberal Democrats will seek Remain voters. And Labour? Their current position is to offer a referendum, perhaps pitting Remain versus the Johnson deal (or, now perhaps less probably, their own renegotiated Labour version.)

Without, as things stand, specifying which option their leadership supports.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Congratulations to Mr Johnson on the simple fact of reaching agreement with the EU. Over to the MPs and their respective political parties to offer a verdict on content.