What can 'weary' voters learn from the early 1920s?

- Published

To govern, we are assured, is to choose. That is customarily taken to mean that those elevated to public office must settle upon one outcome, from a range of options, even if, by so doing, they exasperate a section of the populace.

But let us consider this another way. To govern is to choose.

Of late, at Westminster, there has been a certain dearth of governing, perhaps inevitably. But a cornucopia of choosing.

Those choices, however, have fallen upon the voters, upon the people. Upon the governed, not the government.

It would seem all but certain that another choice will shortly confront that weary electorate. And weary they are.

I wonder whether our elected tribunes appreciate just how exasperated the people are with Brexit and with the collective behaviour of the political class.

'Sick fed up'

Yes, they get it intellectually. No doubt, they hear it in their constituencies, their public meetings and their casual encounters.

This translates into the motivation one now frequently hears expressed in the Commons. That something, anything, must be done. Generally accompanied by sensible, if sometimes sententious, statements to the effect that rushed law is bad law.

So, in a way, our MPs encounter that sense of public frustration. But do they get it viscerally?

Folk are sick fed up of politics. Many are simultaneously angry and scared. Angry at the machinations and manipulation. Scared at the consequences.

I have had conversations with voters in which they have contradicted themselves within a single exchange. Even a single sentence.

Entirely, completely understandably.

Folk will demand: "Why don't they just sort this?" Then they may reflect and add: "But we need to get this right."

Many, frankly, do not get to the reflective stage. They are just furious. Angry, perhaps, that Brexit has not been delivered after three years. Or angry that it was ever contemplated and still persists as a project.

I will presume that this anger/fear duopoly attaches itself mostly to the two biggest parties at Westminster, Conservative and Labour. But the other parties should not believe that they are immune from electoral disquiet.

It is impossible to say, at the moment, how this mood might play out in an election contest but I do not think that politicians should presume business as usual.

Another point to bear in mind is that politicians either genuinely like elections - the thrill of the contest - or they feel obliged to affect delight.

It may seem curmudgeonly but the voters do not tend to see things that way. They are mostly still content to trudge to the polling stations, or to lodge a postal vote.

But they generally expect the political class to respond with a relatively prolonged and uninterrupted period of attempting to set the world/the UK/Scotland/the council area to rights.

In short, after choosing, they long for a little governing. (Which is why one now hears, entirely understandably, a mantra from the SNP that, by contrast with London, they are actively governing in Edinburgh.)

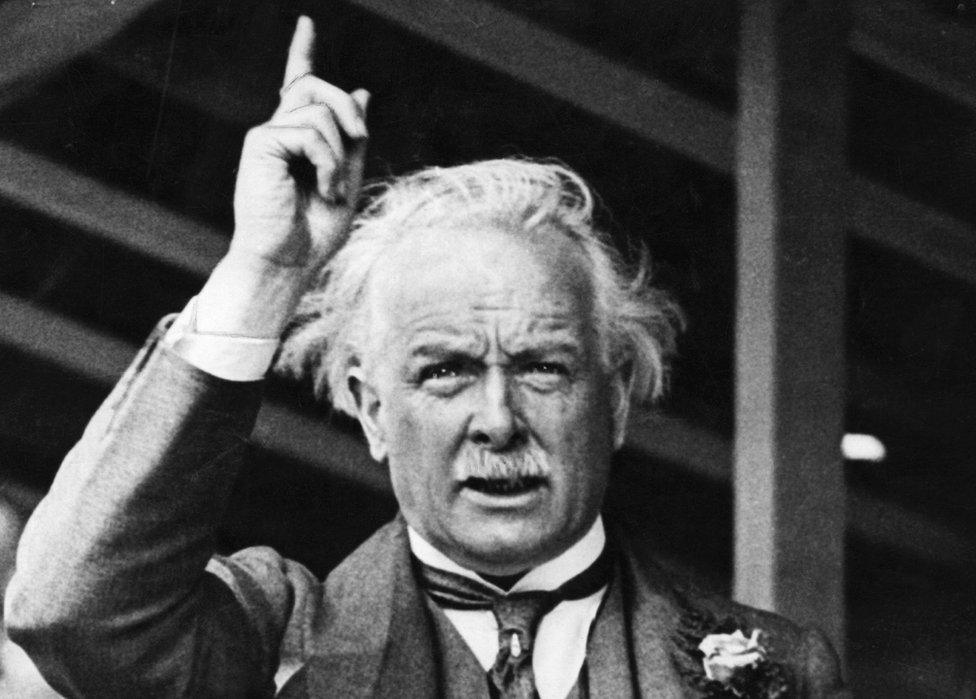

David Lloyd George was prime minister from 1916 to 1922

For the avoidance of doubt, I did not cover the UK general elections in the early 1920s. But I feel there may be lessons there. Or, if not, a little historical immersion, which can be a source of innocent merriment.

In November 1922, the once powerful Liberals were split between the followers of David Lloyd George and those who adhered to Herbert Asquith.

In advance of the election, the Tories had been in coalition with Lloyd George's governing team. As at present, there was an Irish dimension to GB calculations. This was the first election fought after the creation of the Irish Free State.

Bonar Law won for the Conservatives. (Incidentally, Churchill, then a Liberal, lost his Dundee seat in a three way contest, without a Tory opponent.)

But ill-health obliged Bonar Law to hand over to his chancellor, Stanley Baldwin.

Baldwin retained a decent majority in the Commons - and, like Theresa May in 2017, could have carried on governing. But, also like Mrs May, he wanted his own mandate from the people, to strengthen his hold upon the Tories.

Baldwin's Tories won the most seats in December 1923 - but Ramsay MacDonald's Labour and Asquith's Liberals combined to deprive them of power. It was the first ever Labour government.

But it only lasted ten months and, in October 1924, there was yet another general election. Baldwin was returned with a large majority.

Is it possible to draw lessons from this trio of elections, crushed into a short period? Shorter even than the contests in 2015, 2017 and, probably, 2019?

Perhaps. One might say that the 1920s turmoil was prompted by a combination of internal UK disquiet - post war, Ireland, a fragile economy and industrial strife - together with global issues such as monetary tension, the reconstruction of Europe, American influence and the emergence of the Soviet Union.

In short, social and economic upheaval had a direct, persistent, churning impact on the body politic.

Secondly, this period of turmoil was followed by significant party political change.

Tories, mostly, in power; the rise of Labour as a governing force, rather than a protest movement; the eclipse (at the time) of the Liberals; and, a decade later, the formation of the SNP upon a base of Scottish Home Rule demands.

And a final thought. No doubt voters were comparably exasperated when one election followed hard on the heels of the last.

But, looking back, each of those contests counted. They all mattered.