What's in Scotland's emergency coronavirus bill?

- Published

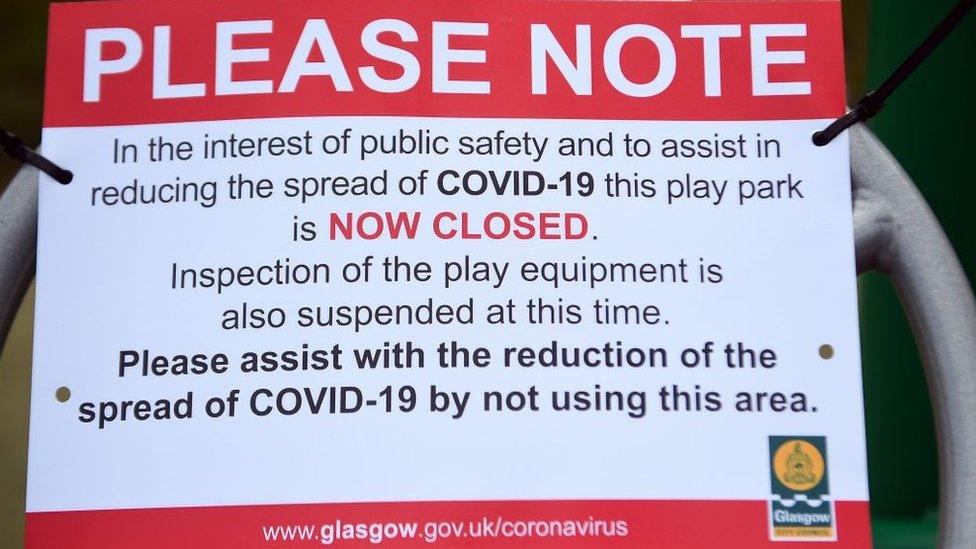

A coronavirus lockdown is already in place across Scotland

MSPs have passed emergency legislation giving the Scottish government new powers to tackle the coronavirus crisis. What is in this new bill, and how is it going to work?

Why is the bill needed?

It hardly needs to be pointed out, but the coronavirus pandemic has meant huge changes to life in Scotland.

The government says the outbreak is a "severe and sustained threat to human life", and that the public health measures needed to limit the spread of the virus "will require a significant adjustment" to how businesses and public services are delivered and regulated.

Many changes have already happened, via Westminster legislation and powers already held by Scottish ministers.

But more needs to be done at Holyrood, particularly in relation to devolved areas like housing and justice. This is where the Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, external comes in.

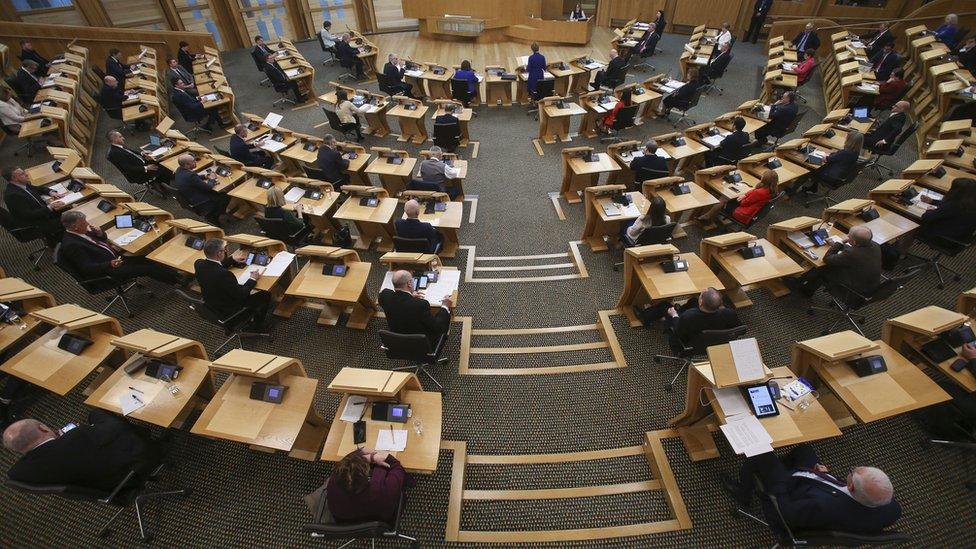

The bill was drawn up on a cross-party basis, and MSPs unanimously agreed to push it through Holyrood after a single day of debate.

Holyrood is sitting for a single day to consider the bill - and will then close for several weeks

What does it mean for tenants?

One of the main functions of the legislation is to give people who rent their homes increased protection from eviction during the pandemic.

New rules will increase the minimum notice period for private and social tenants to up to six months, as long as there are not grounds involving antisocial or criminal behaviour, or if the landlord needs to move into the property themselves.

This is intended to give people time to apply for support or benefits so they can pay bills in the short term, and to make longer-term plans.

Ministers say that while those facing rent arrears should speak to their landlords, the legislation is "an important backstop to prevent evictions and relieve the financial pressure people may be facing".

Proposals by the Greens to toughen these rules by barring eviction notices altogether were rejected by MSPs.

Landlords will not be able to evict tenants in the short term

What does it mean for the justice system?

The bill includes a range of measures to keep the justice system running during the pandemic, to make sure "essential" criminal trials can continue.

It allows for any participant in a criminal or civil proceeding in court to appear via video or audio link from elsewhere, and some procedural hearings could be held entirely over the internet.

The legislation also extends the time limits which usually exist for criminal proceedings, meaning more trials could be delayed. Proposals to have more trials take place without a jury were dropped after an outcry from the legal profession and opposition parties - but could yet resurface in another bill.

The legislation also includes powers for the government to release some prisoners early should so many prisoner officers and staff fall ill that it is no longer safe to operate prisons at their current population levels.

Nicola Sturgeon has stressed that this power would only be used as a "last resort" - subject to vote in parliament - and would exclude prisoners on life sentences or who have been convicted of sexual crimes.

Some prisoners could be released if staff levels are badly hit by the virus

What does it mean for businesses and public bodies?

The legislation also includes a number of provisions to keep businesses and public services running during the outbreak.

This includes changes to deadlines over planning and licensing rules for local authorities, as much business in this area has been put on hold with pubs and construction sites closing down.

Local authorities will also be allowed to exclude the public from their meetings "on health grounds", something the government said was a "reasonable and proportionate measure to protect the public and council members".

The bill also extends the deadline for public bodies to respond to Freedom of Information requests from 20 days to 60 days. After concerns from opposition parties, ministers agreed that this would not apply to the government itself and that extensions should only be used in a "targeted way".

The bill also includes short-term protection for debtors, extending the period for which creditors are barred from taking action against people and firms - a moratorium - to six months.

Scottish councils will be able to exclude the public from meetings

How long will the government have these powers?

Ministers have insisted that these emergency measures will be "strictly limited to the duration of the outbreak".

The legislation includes a "sunset clause", meaning that most of it will automatically expire six months after it comes into force.

MSPs will be able to vote to extend this for another six months if necessary, and then for another six months after that, but this is the absolute limit - so the measures in the bill have a maximum duration of 18 months.

Ministers have also pledged to report back to Holyrood every two months about the use of the emergency powers.

Seats have been removed in the Holyrood chamber to maintain social distancing between MSPs

What isn't in the bill?

A range of measures to contain the virus and help support communities and the economy have already been implemented without the use of Scottish-specific legislation.

For example the UK government's moves to support workers, both those under contract and the self-employed, are being implemented without new laws being passed.

The new powers given to police officers to enforce to social distancing rules are underpinned by UK legislation, and also do not require specific legislation at Holyrood - although they are also subject to a "sunset clause".

The whole Holyrood bill is designed to "complement and support" the UK legislation, which MSPs formally gave their backing to the day before it passed.