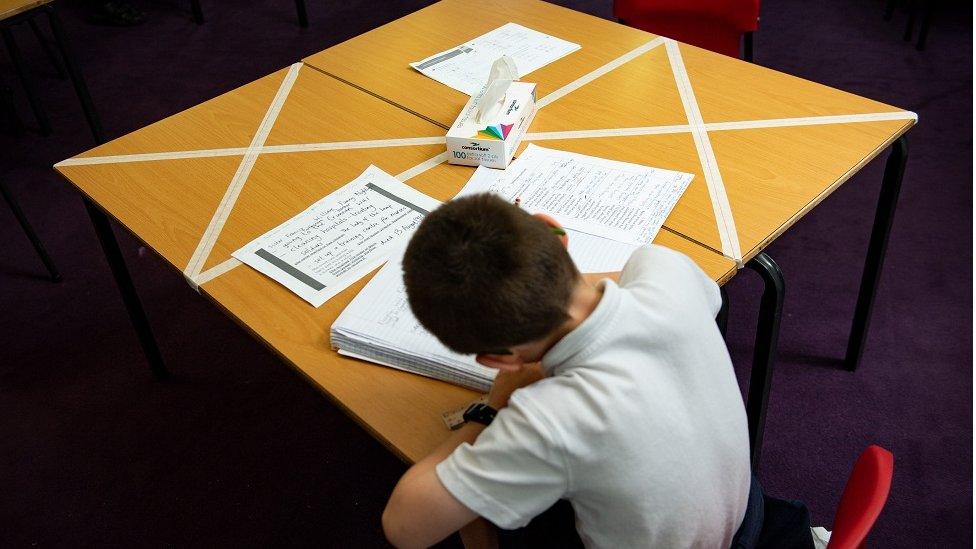

Coronavirus: Parent power changes Scottish school return plans

- Published

The next time someone tells me politics doesn't matter, I'm going to remind them about the debate over schooling this week.

Parent power, backed up by political campaigning, has produced a significant shift in Scottish government thinking.

Last Sunday, the part-time return of Scottish schools on 11 August, with children doing additional work at home appeared to be the default position, external.

Within a few days, the first minister described this "blended learning" approach as a "contingency" and said she'd move heaven and earth to reopen Scotland, especially schools.

In effect, the default became the back up plan.

Expectations raised

In the middle of a pandemic, Nicola Sturgeon cannot and has not guaranteed schools will be back 100% after the summer holidays and that there will be no remote learning.

But it seems to me, that outcome - or something close to it - is now the goal. Expectations have been raised.

Achieving that would first of all require a continued suppression of coronavirus, towards which good progress is being made in Scotland.

It would also require a change to the 2m (6ft) rule on social distancing.

The rule has already been reduced to 1m (3ft) for pupils in Northern Ireland and the Scottish government has asked for fresh advice from its experts within two weeks.

Getting children back full time in August would also need acceptance from parents, teachers and their representatives.

The powerful EIS teachers' union, for instance, has made clear it will not compromise on safety and wants more teachers recruited.

32 separate plans

At this point, it's worth remembering that the delivery of school education is a local authority function. Councils need to be on board too.

As they have been developing 32 separate plans for blended learning, it has become clear that wide variation in classroom provision could result.

There was an outcry when it emerged Edinburgh's offer could include as little as one day a week in school for pupils, whereas other councils were aiming for two or more classroom days.

The first minister made clear one day a week would not be acceptable and promised to scrutinise council plans closely and consider setting minimum requirements.

She knows that the political reality is that if councils are perceived to under provide, the Scottish government will get at least some of the blame.

One way for ministers to avoid that and lots of wrangling with councils, is to strive to create conditions that minimise the need for blended earning.

As the first minister said at her coronavirus briefing on Friday: "If we can get to a point where we don't need it at all, of course we'd prefer that".

That preference or aspiration has still to be turned into a firm policy commitment and Nicola Sturgeon's political opponents will keep pressing her for that.

The first minister has said she will "move heaven and earth" to get schools open again

The decision by the UK government to target the full return of schools in England in September adds an extra dimension to the debate.

If anything like a full return in August is achieved, it may have knock-on effects for the broader easing of lockdown, with some other restrictions lasting longer.

Many would regard that as a price worth paying for the resumption of a more normal system of education and the chance to get back to work.

Others may require greater reassurance that arrangements are safe and any coronavirus cases in schools can be effectively contained.

But those who have raised their voices to argue for an improvement to the "blended learning" models that were emerging have changed the debate.

Political action, in this case, has mattered and it has made a difference.

- Published28 May 2020

- Published22 May 2020