Could a new independence party reshape Scottish politics?

- Published

Could a new pro-independence party make the difference in the campaign for indyref2?

A series of SNP and pro-independence campaigners have suggested setting up a new party ahead of the Holyrood elections in 2021. Why are they doing this, and are they more likely to split the nationalist vote or secure a mandate for a new referendum?

What is this all about?

The SNP continues to enjoy a dominant position in Scottish politics, with polls suggesting, external the party will continue its electoral winning streak in 2021.

So it might seem odd to many outside the political bubble that supporters of the party - including one of its own MPs - are advocating voting for someone else at that election.

The answer lies in the Holyrood electoral system, which makes it hard for one party to win an outright majority of seats.

The "additional member system" features 73 constituency seats, elected on a traditional first past the post (FPTP) basis, and 56 "list" seats scattered across eight regions.

The way the system actually works is complex, but the goal is simple - proportional representation. In short, the more constituency seats you win, the harder it is to win list seats.

Counting up the votes in an Additional Member System election can prove complicated

To take 2016's election as a case study, half a million people voted for Labour in constituency contests, but thanks to the all-or-nothing nature of FPTP this yielded only three MSPs. So 22% of the vote won 4% of the seats.

However, the party's 435,000 votes on the list ballot saw them pick up a further 21 seats - meaning that overall, they got roughly a fifth of the votes in the country, and roughly a fifth of the seats at Holyrood.

At the other end of the spectrum, in the constituency contest the SNP won 46.5% of the vote, and 80% of the seats (59 of them). This meant that on the list, almost a million votes only produced four regional MSPs.

The additional member system balanced things out as it is designed to do - with just under half of the vote, the SNP got just under half the seats on offer overall.

To come to the point, some supporters of independence conclude that it would be much easier to win a Holyrood majority if there was a list-only party which could sweep up the regional seats which the SNP may struggle to reach.

What is the proposal?

Proponents argue that a new list party could produce extra pro-independence MSPs - at the expense of unionists

The argument is that if the million people who voted SNP on the list in 2016 had backed another party, in theory they could have returned dozens of pro-independence MSPs instead of four.

If this party were to stand only on the list, they would not have any constituency seats to hold them back as far as the formulas are concerned.

The SNP could take the constituency vote, the new party would clean up on the list and the two would add up to an overwhelming mandate for indyref2 - or so the theory goes.

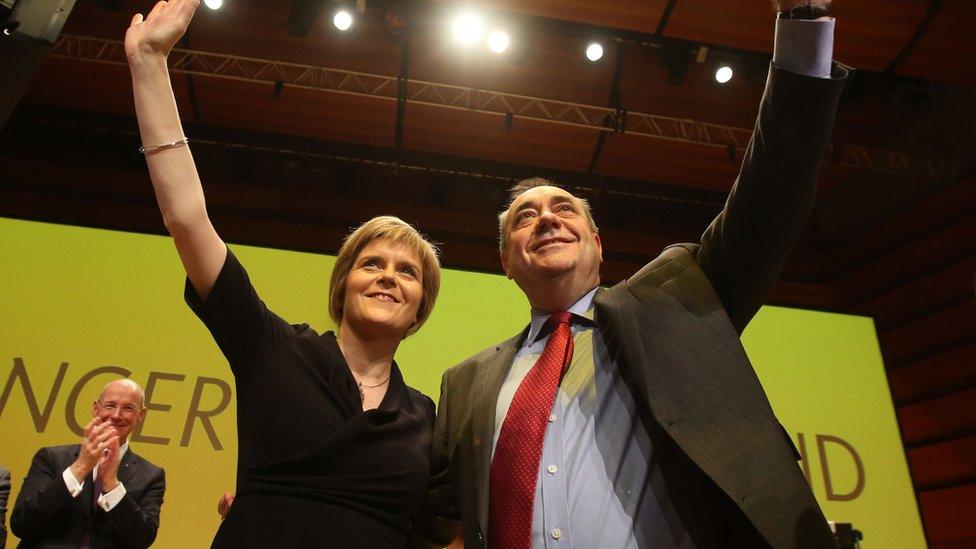

But what is this "new party"? A number of different vehicles have been suggested, from the "Independence for Scotland Party" to one led by Wings Over Scotland blogger Stuart Campbell - who has in turn suggested former SNP leader Alex Salmond could set up his own group.

The latest is the "Alliance for Independence" proposed by former SNP MSP Dave Thompson, which he envisions as an umbrella group uniting smaller pro-independence campaigns.

Proponents believe this would be more productive than the "both votes SNP" approach of previous years, which Mr Thompson - a 55-year veteran of the party - says "will achieve nothing".

This approach has been endorsed by figures including sitting SNP MP Kenny Macaskill, who said: "With success on the constituency basis resulting in limited progress on the list, 'both votes SNP' just doesn't work."

What is the SNP's position?

The SNP is unlikely to stray from its "both votes SNP" strategy

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a political party, the SNP is loathe to urge people to vote for anyone else.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said he "can't understand the logic" of a list-only party, citing the precedent of the SNP majority in 2011 successfully triggering a referendum.

The last thing the party's leaders want to be is complacent. They cannot simply assume they will walk away with the lion's share of constituency contests - indeed, taking elections for granted is a very good way to lose them.

So if the party were to lose a constituency seat, say in Glasgow, they would want to give themselves the best chance possible of picking it up again on the regional ballot by stacking up as many list votes as possible.

They will be decidedly wary about splitting the vote. One advantage the SNP have long had over their unionist opponents is that in a country divided pretty evenly down the middle on the constitutional question, they have a near monopoly over one half of the vote - while the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems have to scrap over the other half.

Another issue for them is messaging. "Vote SNP" is an easy slogan to paint on the side of a bus. "Vote SNP on one bit of paper and a pro-independence alternative of your choosing on the other" is slightly less pithy.

Is this a new idea?

Other pro-independence parties have contested the Holyrood list in previous years

The Scottish Greens would point out that they are quite a prominent pro-independence party that chiefly does well on the regional list.

But other smaller outfits have also come forward at previous elections - and failed to make any impact at all.

In 2016, RISE contested the regional lists, with a former SNP MSP on their ticket, but ultimately polled fewer votes than the Scottish Christian Party.

Solidarity - Tommy Sheridan's breakaway from the Scottish Socialist Party - did a little better, but still only managed 0.6% of the vote and zero seats.

There is an argument that a figurehead like Alex Salmond (who, to be clear, has said nothing at all on the subject) and a platform focused solely on independence could see a new party make a bigger impact - but if the SNP actively oppose the idea, that impact could be in splitting the vote.

The pro-independence side are not alone in debating whether they should try to game the list system, incidentally - George Galloway is attempting to set up an "Alliance for Unity" that sounds a lot like a unionist version of Mr Thompson's umbrella project.

Would it work?

The next Holyrood election is due in May 2021

This is the million-dollar question, and the hardest one to answer.

The majority of 2011 will be much cited in this debate, but it is actually something of an outlier. In that election, the SNP broke the system - they took 53% of the seats at Holyrood despite "only" winning 45.4% of the constituency vote and 44% of the regional one.

It happened essentially by fluke - the stars aligned for the party in just the right way, with the placing of the 53 constituencies won around the country somehow still allowing the party to pick up 16 list MSPs.

There isn't really a way to strategise for that to happen again in the same way - it is by no means a blueprint for victory in 2021. The only way to be sure of a majority at Holyrood is to literally win a majority of the votes cast in Scotland.

That is a tall order for one party alone. The SNP's landslide in the 2015 Westminster election saw them hit 50% of the vote, but in December they were back at 45% - a familiar figure to any Yes voter.

Would having two of Scotland's most formidable campaigners in opposing camps be helpful to their cause?

The paradox is that, if it had the open support of the SNP, a list-only party could provide a theoretical route to producing a larger cohort of pro-independence MSPs. But at the same time, it is difficult for the SNP to support it without risking their own position.

It would be a move fraught with complexity and danger, and Nicola Sturgeon is not exactly known as a gambler.

And when it came to the campaign, would any new party really exist harmoniously alongside the SNP, which has become an electoral juggernaut partly by dint of its unity of purpose?

Imagine Mr Salmond did end up fronting a new party - would a Salmond vs Sturgeon debate really be beneficial to the cause both politicians champion, or would it exacerbate tensions about the current first minister's cautious approach to indyref2?

There are also wider questions over whether a pro-independence majority spread across several parties has the same impact as it does when a single party wins a thumping mandate.

After all there is currently a pro-independence majority at Holyrood, with the Greens backing the SNP - which has conspicuously failed to produce a referendum, despite MSPs voting in favour of one several times.

The debate underlines one thing - despite coronavirus continuing to dominate the agenda, Scotland is less than a year away from an election. More and more, party politics is coming out of lockdown.