Scottish election 2021: Unusual - but extremely high stakes

- Published

It has been a more sanitised campaign - although not without some memorable moments

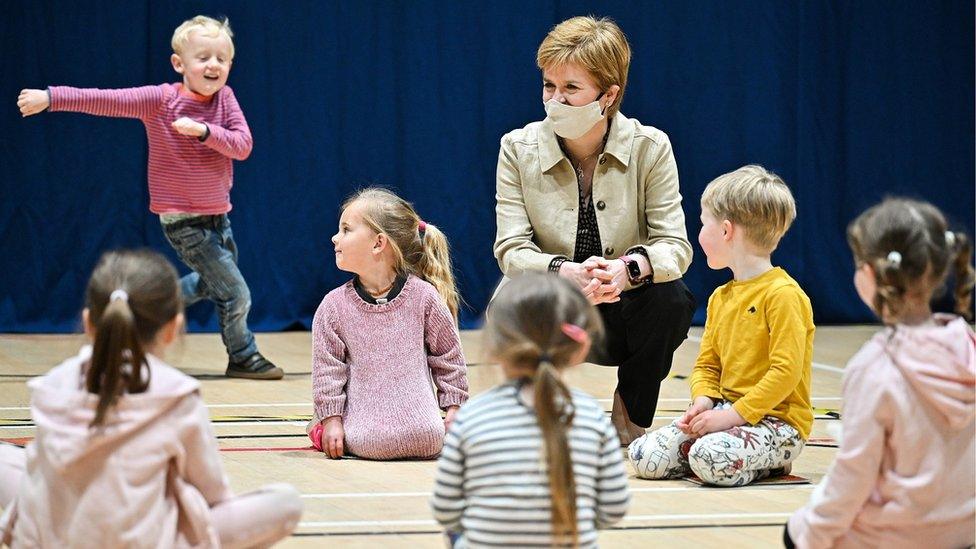

Hands left unshaken. Babies spared the kisses of publicity-hungry politicians. It is the most unusual Holyrood election.

Close contact with voters and their unsuspecting offspring is not allowed under Covid rules and that has changed the character of this campaign.

Social distancing has spared political candidates from much of the potential jeopardy of facing the public in community hustings or TV debate studios.

The pandemic has produced a more sanitised election - less eventful, even a little dull at times.

There have been some memorable moments. Alex Salmond setting up the Alba party. Nicola Sturgeon conceding she took her "eye off the ball" over drug deaths. Anas Sarwar's dance moves.

Nicola Sturgeon has said she would would always put tackling Covid first

In some ways, what has not happened is more notable.

For the first time in Holyrood's short history, the UK prime minister has not appeared on the Scottish campaign trail.

Boris Johnson's unpopularity in Scotland may go some way to explaining his absence. The controversy surrounding his administration has ensured he's featured in the campaign anyway.

None of that is to suggest the Scottish election does not matter. It absolutely does. Big time.

Douglas Ross' main aim is to deny the SNP a majority

Voters are choosing who will run the Scottish government for the next five years and lead Scotland's recovery from coronavirus.

They are also deciding whether or not there will be a big push for another independence referendum in the next parliament - something that affects the whole UK.

If a majority of those elected to Holyrood back indyref2, a major political wrangle between the Scottish and UK governments is likely to follow.

However low energy this election might be, the political stakes are extremely high.

SIGN UP FOR SCOTLAND ALERTS: Get extra updates on BBC election coverage

What are the parties promising you?

Use our concise manifesto guide to compare where the parties stand on key issues like Covid-19, independence and the environment.

Barring an unforeseen event of seismic proportions, the SNP are on course to win their fourth consecutive term in power.

None of the other parties dispute that. They are not even trying to replace Nicola Sturgeon as first minister.

The big question is whether she will have an overall majority in the next parliament - more seats than all the other parties put together - or fall a bit short.

One senior SNP minister told me it was just too hard to predict the outcome, not least because the lack of doorstep campaigning means they have poorer data than usual.

The minister could see how it might be possible to win a majority of Holyrood's 129 seats by cleaning up in the constituency vote, but equally how that might be prevented.

Anas Sarwar is trying to challenge the Conservatives for second place

The main ambition of Conservative leader Douglas Ross is to deny the SNP that majority - a goal he shares with Labour's Anas Sarwar and the Liberal Democrats' Willie Rennie.

Mr Sarwar is also trying to challenge the Tories for second place.

Without an overall majority, pro-UK parties think Ms Sturgeon will find it harder to press the case for an independence referendum.

There has been an SNP/Green majority for independence at Holyrood since the last election and their calls for a referendum have been resisted by the UK government.

When the SNP won an outright majority in 2011, the then prime minister David Cameron accepted that as a mandate.

That set a precedent but there is no agreed definition of the political circumstances that should prevail for indyref2 to happen.

The Greens want the wealthy to pay significantly more in tax

Nicola Sturgeon believes a simple majority at Holyrood - with or without Green support - should be enough. She would use that to pass a referendum bill.

If that happens without Westminster agreement she would be prepared to defend the legislation in court in the likely event of a legal challenge.

The SNP insists the referendum would only go ahead if it was within the law. They want it to happen before the end of 2023, if the Covid crisis has passed.

That is another ill-defined feature in this debate. When exactly is the crisis over?

Nicola Sturgeon has said she would use judgement to decide and would always put tackling Covid first.

Willie Rennie is opposed to a second independence referendum

She has tried to focus hard on the principle of what she calls "Scotland's right to choose" its own future.

She has been less keen to discuss the practicalities of delivering independence from the UK after Brexit.

Ms Sturgeon would rather defer hard questions over currency, banks, the English border, trade and EU membership until any referendum campaign.

These are questions her Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat opponents think must be raised in the discussion over whether or not there should be another referendum.

They think holding indyref2 at any point in the next five years would sap energy from efforts to rebuild the NHS, education and the economy.

In devolved policy areas, the Holyrood parties have remarkably similar plans for Covid recovery.

How does the Scottish voting system work?

Election 2021: How does Scotland's voting system work?

In the Scottish election people have two votes, one for a constituency MSP (like in the UK general election) and another for the regional ballot, often referred to as the "list vote".

The list vote is usually for a party rather than an individual.

The parties are then allocated a number of MSPs depending on how many votes they receive - once the number of constituencies already won in that region is taken into account - to make the overall result more proportional.

There are eight electoral regions, each with seven regional MSPs.

There's broad consensus on NHS investment, recruiting more teachers, doubling the child payment to £20, expanding free childcare and the provision of free school meals.

All sides have big spending plans despite the Institute for Fiscal Studies warning of a "disconnect from the fiscal reality".

The Conservatives aspire to reduce personal taxation over time. Most other parties are not proposing big tax changes, except the Greens - who want the wealthy to pay significantly more.

The policy differences are there if you look closely enough but by far the biggest dividing line in this election is the constitution.

While the pandemic has turned almost everything upside down, the perennial question in Scottish politics over independence and the union remains persistent in election 2021.

POLICIES: Who should I vote for?

CANDIDATES: Who can I vote for in my area?

PODLITICAL: Updates from the campaign

- Published7 May 2021

- Published7 May 2021

- Published22 April 2021