Does political pressure shape pandemic decisions?

- Published

Nicola Sturgeon and Boris Johnson have very different styles of leadership - but have made the same calls throughout the pandemic

The Scottish government has reiterated plans to lift Covid-19 restrictions in the coming weeks despite a spike in cases. What political pressure are ministers under, and how has it shaped decision-making throughout the pandemic?

Scotland's exit from lockdown appears to be following the same pattern as much of the rest of the pandemic.

The rhetoric from politicians in Edinburgh is notably more cautious than that of their counterparts in London, but ultimately they are all traveling on the same path.

There is an extra set of steps on the Scottish route - moving to level zero on England's "freedom day" of 19 July, before scrapping most legal restrictions three weeks later - but the destination and determination to reach it are the same.

Scottish ministers may not use words like "irreversible" or "guarantee" in the rather more flamboyant style of Prime Minister Boris Johnson, but they still bat away any notion of a delay or change of plans.

Listen to whoever is sent out to do the latest round of interviews, and they generally find a way to glide smoothly past questions about pressing the brakes again.

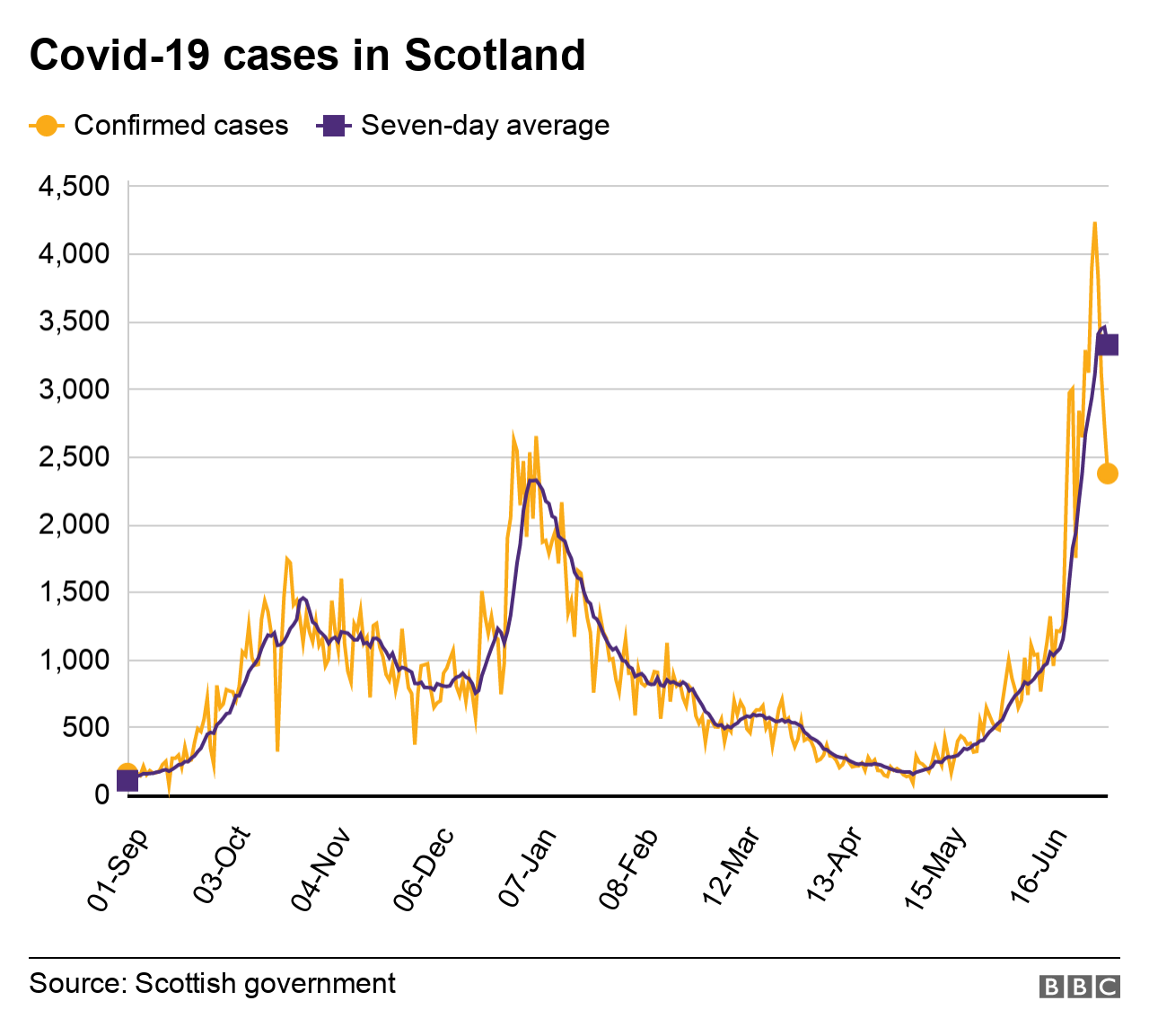

This seems a curious thing on the surface - why would a government which has cultivated a reputation for caution wave away the record case numbers which have left Scotland dominating the Euros in the worst way?

The answer is the same as it has been since the world turned upside down in March 2020. Politicians face a fiendishly complex situation, a minefield of competing harms, priorities and uncertainties.

And for a number of reasons, it makes sense for governments across the UK to pick their way through this minefield along a similar path.

To start with, the virus is a unifying factor - it has no interest in borders, and scientific advice has been broadly similar wherever you live.

Leaders are loathe to stray far from the twin totems of The Science and The Data, especially given the prominent role of advisers and clinicians in fielding questions and communicating strategy.

On the political side, parts of the pandemic response have been run from Westminster because they sit in reserved areas - things like border control and the furlough scheme. The vaccine programme - the biggest factor in the current move away from restrictions - is also a UK-wide success story.

And for all the differences in style and presentation, the big decisions under devolved control have mostly gone the same way north and south of the border - from stay-at-home orders to care homes and Christmas.

This is not to undersell the value of good presentation, incidentally. Particularly in the early days of the pandemic, clear and consistent messaging was one of the most important elements in guiding the public through a fast-changing and frankly scary situation.

It's also not to suggest that anyone has been taking decisions on the basis of anything other than what they genuinely think is best for the country (the bad news for political partisans is that if you accept this is the case for one government, it necessarily also applies to others which take exactly the same actions).

It is however much easier to pitch a message - particularly one as nuanced as the spiderweb of rules and regulations we have lived under for a year-and-a-half - when it chimes across the political spectrum.

The success of the vaccine programme is the main reason why governments now feel safe to ease restrictions

There is a measure of political cover in acting together. Before the inquiries have even begun, we have already heard former Health Secretary Matt Hancock defend the discharge of patients from English hospitals into care homes by essentially saying "well the Scottish government did it too". Nicola Sturgeon also frequently points to the fact governments the world over are wrestling with similar issues.

And equally when administrations do dare to take diverging paths, it sparks immediate questions. Why can people in Carlisle have X when folk in Gretna are stuck with Y?

The pattern is perhaps reinforced by the fact that opposition parties are in a similar bind.

The major parties are in government in other parts of the UK, and thus need to have one eye on decisions made elsewhere before castigating ministers here for doing the same. Even the opposition are locked into a "four nation" approach of sorts.

The Conservatives are keen to make hay about Scotland's record-high case rates, but given SNP ministers are treading broadly the same path as those in Whitehall they have to do so without demanding much in the way of change.

Labour meanwhile is in charge in Wales, where ministers have not yet set any dates but are making very familiar noises about the weakening link between infections and serious illness.

If opposition MSPs were to suggest a completely radical approach, it would raise questions about why their colleagues, who are actually in charge of something, don't agree.

They also have fewer opportunities to set out their own stalls at the moment, given Holyrood is in recess until September - only reconvening for two virtual sessions at major decision-making junctures.

Face coverings may remain a regular feature in Scotland for longer than in England

By late summer, it seems likely that any differences between the few remaining restrictions in Scotland and England may be largely cosmetic.

There seems to be a divide of sorts over face coverings, which Scottish ministers remain slightly more keen on.

However, it is unclear whether they will be required by law, or if it will simply be a matter of guidance - and thus effectively the same as the arrangement in England.

Remember that when the face mask regulations were introduced, it was clear that there was not going to be a huge wave of enforcement. The idea was that putting the guidance into law underlined to people that it was a serious matter, encouraging more to comply - which they did, overnight, without the need for fines to be dished out en masse.

The big question is whether the post-pandemic landscape will be defined in the same way as the response to the immediate crisis. Will all corners of the UK seek to build back from Covid in the same way, or will different visions take hold?

Many of the same calculations will come into play - we have already heard questions about parity between NHS pay deals in different areas, and rows over when UK-wide schemes like furlough are phased out.

But the Scottish government clearly has designs on a very different future north of the border, given its plans for an independence referendum. In that sense, divergence from the UK is the SNP's core policy.

That said, one similarity remains - how far those plans are progressed in the year to come may depend heavily on the state of the pandemic, and relations between the governments in Edinburgh and London.

Related topics

- Published6 July 2021