The deal is done - so what lies ahead?

- Published

Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater will now both join Nicola Sturgeon's government

The deal is sealed.

SNP members, Green members and the Green party's national council have all emphatically endorsed the power-sharing deal between the two parties.

That means Greens will now enter national government for the first time anywhere in the UK, with Green co-leaders Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater becoming ministers.

The first minister, Nicola Sturgeon is expected to formally appoint them to her team next week when Holyrood returns from the summer break.

Their appointment is subject to the approval of MSPs but the result of that and most other Holyrood votes is now a foregone conclusion.

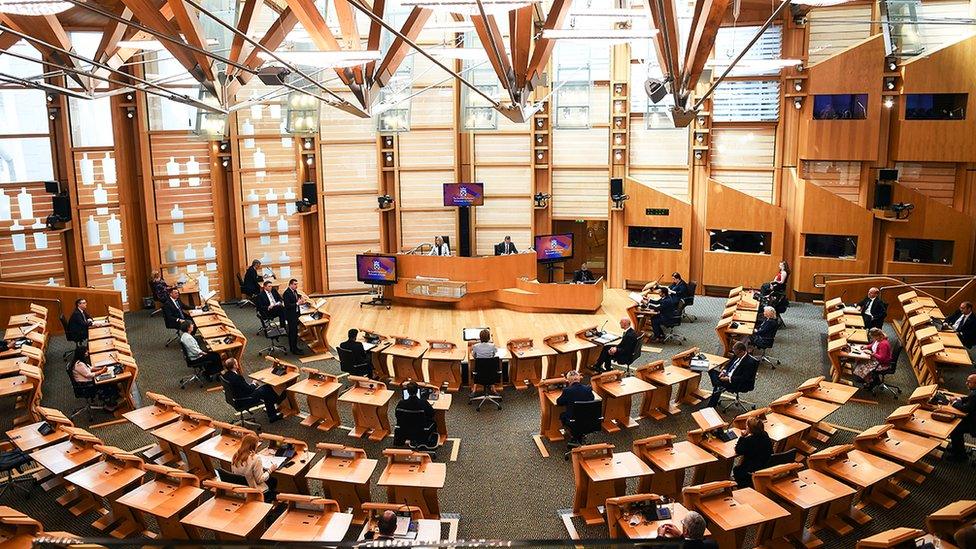

That's because one of the key features of this SNP-Green alliance is a built-in majority in Parliament for their shared programme and when it comes to budgets and votes of confidence.

The SNP has 64 votes - 1 short of an overall majority. With another 7 Green votes, they have more than enough clout between them to see off the sort of opposition ambushes that wrong footed the SNP in the last parliament.

That will make the job of the opposition harder at Holyrood. Although in theory, in some guises, the Greens will still be acting as an opposition party and receiving funding from Parliament to assist with this work.

It has yet to be decided by Holyrood's presiding officer, Alison Johnstone - who gave up Green membership to take on that politically neutral position - if the party will still get a weekly chance to question the first minister.

The deal gives the SNP-Green alliance a majority at Holyrood for their shared programme

This partnership is not a full coalition like the Liberal Democrats had with David Cameron's Conservatives at Westminster or the Lib Dems had with Labour in the first two terms at Holyrood.

While the Greens have signed up to the bulk of the government's programme, including road building schemes they don't much like, they have negotiated opt outs in a range of policy areas.

These include the desirability of economic growth, aviation, field sports and private schools - areas where reaching agreement with the SNP would have been impossible.

On these topics, the Greens will be able to criticise the government of which they otherwise form part.

It is a power-sharing experiment that's never been tried in the UK before. It's based on the understanding New Zealand Greens have with the government of Jacinda Ardern in Wellington.

It seems to me to leave plenty of scope for future tensions between the two parties. That is especially true when it comes to the differing positions they take on future oil and gas extraction.

While the Greens want to block new oil fields and phase out current sources of production within a decade or so, the SNP is much more cautious about abandoning fossil fuels.

During the negotiation of the cooperation agreement, Patrick Harvie said the Greens were putting "maximum pressure" on the Scottish government over this.

Environmentalists are strongly opposed to the development of the Cambo oilfield

Nicola Sturgeon did announce a policy shift - calling on the UK government to review proposed developments like the Cambo field in light of the climate crisis.

The Greens welcomed her new position but said it did not go far enough. The issue may well resurface in the build up to the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November.

Because the first minister appears to be leaning towards a more oppositional position on Cambo, the Conservatives are already campaigning as if the SNP's association with the Greens is a gift to them in the oil producing north east of Scotland.

The Tories have dubbed the deal a "coalition of chaos" partly because both the SNP and Greens want another independence referendum when the pandemic eases and preferably before the end of 2023.

Their partnership clarifies the majority for independence that already existed at Holyrood by turning it into a government majority.

Ministers will use that to amplify their case for another referendum although it is unlikely to shift the UK government's opposition to granting Holyrood the explicit power to hold the vote.

So the SNP get to form a majority, independence-supporting government and freshen up their look after 14 years in power, with enhanced Green credentials in time for COP26.

For the Greens, this deal is about transitioning from a party of pressure and protest into one of power. It is a chance to deliver a bit more of their manifesto.

Benefits and risks

They look forward to claiming credit for greater spending on railways and cycling, more wind farms, a new deal for tenants, rent controls and a new national park.

They hope that being in government, attending cabinet from time to time, will allow them to exert further Green influence.

They hope all that will boost their election chances next time and ensure they avoid the decimation the Lib Dems suffered after their Westminster coalition.

They know there are also risks. They may find themselves obliged to defend unpopular policies and could share the blame for things the government gets wrong.

One of the co-leaders of the New Zealand Greens, James Shaw described that to me rather colourfully as "swallowing a few dead rats".

In other words, power-sharing comes at a price. But Greens have decided it is a price worth paying for the opportunity to go into government for the very first time.