Supreme Court upholds challenge to two Holyrood bills

- Published

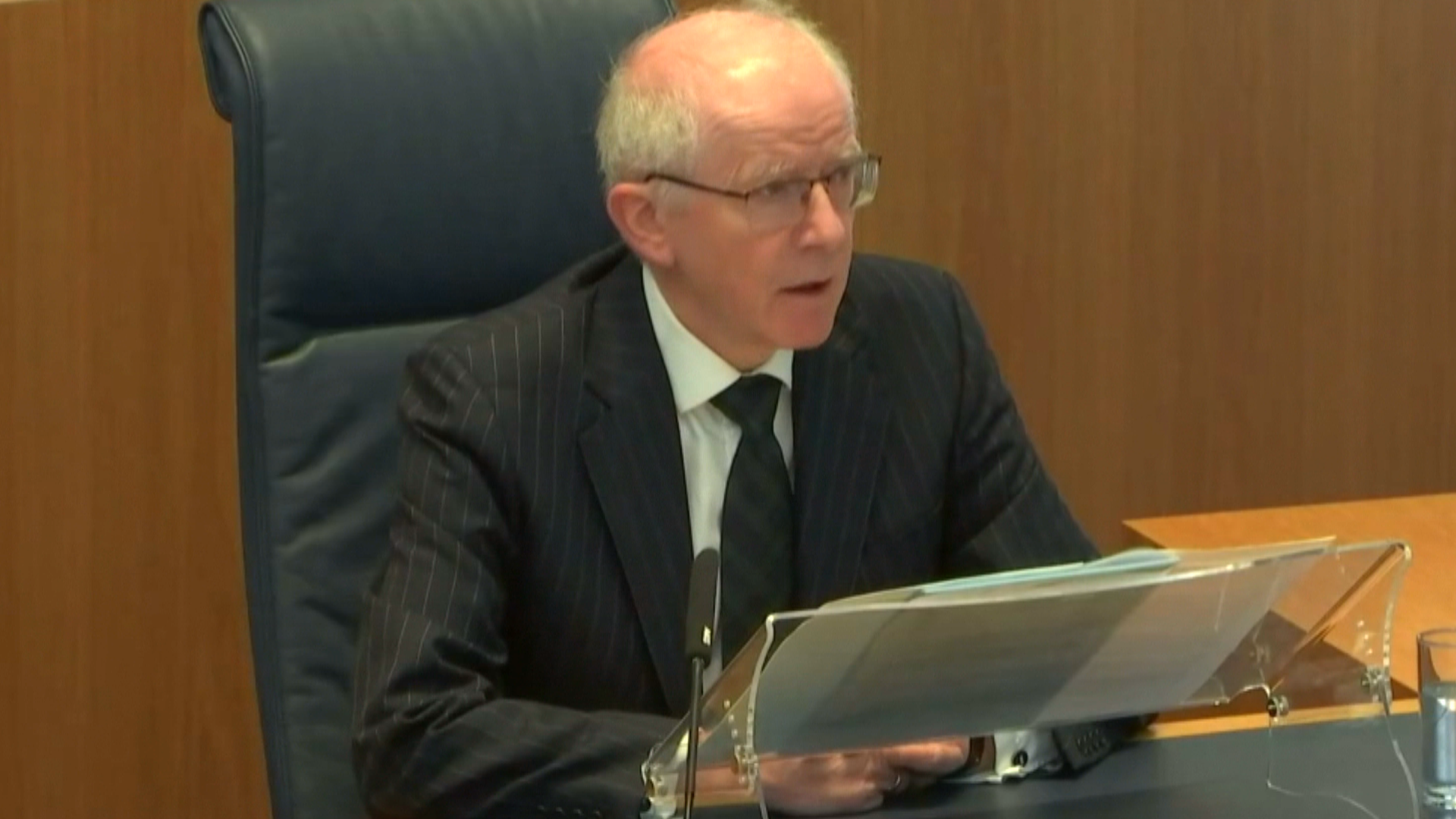

Two days of legal arguments were heard at the court in June

Judges at the Supreme Court have ruled that provisions in two bills passed by MSPs were beyond Holyrood's powers.

MSPs unanimously backed the bills - which enshrine treaties on children's rights and local government in Scots law - prior to May's Holyrood election.

However after a challenge from UK law officers, judges said the legislation could affect Westminster's ability to make laws for Scotland.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said this showed the limits of devolution.

The bills will now go back to Holyrood to be reconsidered and amended by MSPs, with the Scottish government saying it is committed to bringing them into law "at the earliest possible opportunity".

Opposition parties backed this, but accused Scottish ministers of playing "cynical political games" over the issue.

What were the bills?

The challenge concerned two bills passed in the closing days of the previous parliamentary session, which both aimed to incorporate aspects of international treaties into Scots law.

The first was the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which the Scottish government said would set a legal requirement for public authorities to comply with international standards on children's rights.

The second was the European Charter of Local Self-Government, which was put forward by former independent MSP Andy Wightman.

Neither bill was controversial at Holyrood, and both were passed unanimously by MSPs. However, the UK government did raise concerns about them, and submitted a challenge to the Supreme Court claiming they were beyond the remit of the devolved parliament.

UK law officers insisted the challenge was not based on the substance of the legislation - the UK government signed up to both of the treaties in question in the 1990s and says it is "deeply committed" to protecting children's rights - but on its potential impact.

Their submission to the court said the standards set by the bills could be applied to laws passed at Westminster as well as Holyrood - meaning the Scottish courts would have "extensive powers to interpret and scrutinise primary legislation passed by the sovereign UK parliament".

Lord Reed said the bills would have to return to the Scottish Parliament so the "issues can receive further consideration"

The Scottish government defended the legislation, claiming that stripping provisions from the UN Convention bill would "limit the protections available for children and young people".

Announcing the verdict on Wednesday morning, Lord Reed said the court had unanimously agreed that four provisions of the UN Convention bill and two provisions of the European Charter bill were outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

The court agreed that they would affect the UK government's ability to make laws for Scotland, in breach of the Scotland Act.

The bills will now return to Holyrood and can be looked at again by MSPs in a "reconsideration stage" to bring them into line with the court's ruling.

This is the case for Mr Wightman's members bill despite the fact he is no longer an MSP - it can instead be taken on in parliament by an alternative member.

Understanding the nuances of the ruling

Inevitably, the judgement is a little more complex and nuanced than you might be led to believe by politicians of all stripes who fired out comments within minutes of it being handed down.

None of the arguments heard in court had anything to do with children's rights or local government - this was about the law-making process rather than the principles of the bills themselves.

And this means it has tapped into a more fundamental dispute between ministers in Edinburgh and London, about the extent of Holyrood's powers.

Clearly, the Scottish government thinks there should be no limit on Holyrood's powers, because they think Scotland should be independent. But this case tells us little about the prospects for a fresh referendum, or how the courts might view legislation for one.

Ultimately, the two bills could likely be brought into line with the judgement with a few strokes of a pen - Mr Wightman says it should be "straightforward".

But that may well be lost amid the sound and fury of the familiar constitutional row which the ruling is sure to provoke.

Mr Swinney said the Scottish government "fully respects the court's judgement", but was "bitterly disappointed".

He said the ruling would require "careful consideration", but said the government remained committed to incorporating the UN Convention into Scots law to the greatest degree possible.

The deputy first minister added: "One thing is already crystal clear - the devolution settlement does not give Scotland the powers it needs."

Two days of legal arguments were heard at the court in June

Meanwhile Mr Wightman said he was "disappointed but not surprised" by the judgement, saying that "the amendments required to resolve the incompatibility are straightforward".

He added that while it had raised a wider point about Holyrood's powers, a "huge amount of nonsense" was likely to be talked about the ruling.

Opposition parties still back getting the bills into law, but were critical of the Scottish government's approach.

The Scottish Conservatives said the SNP had "shamefully used children's rights to play nationalist games".

Constitution spokesman Donald Cameron said: "There was never any dispute over the substance of the policy, only the legality of parts of the bill. But the SNP sought to politicise it from the very beginning."

Labour MSP Sarah Boyack said: "This court case has been a needless distraction from what really matters. This damning verdict makes it clear that the SNP have been playing cynical political games at the expense of children's human rights."

And Lib Dem MSP Willie Rennie said it was "depressingly predictable" that the government had waited for a "constitutional clash" before making changes to the legislation.

- Published6 October 2021

- Published28 June 2021