The A-Z of winning a council seat in Scotland

- Published

Politicians are meant to be chosen based on their policies, personal integrity and popularity. But in Scotland's council elections, there was another factor at play - the alphabet.

The latest set of local authority polls provided fresh evidence of the "list order effect", where candidates closer to the top of the ballot paper attracted more votes than party colleagues further down.

What is behind this phenomenon, what could be done about it, and are these changes likely to happen?

What's the problem?

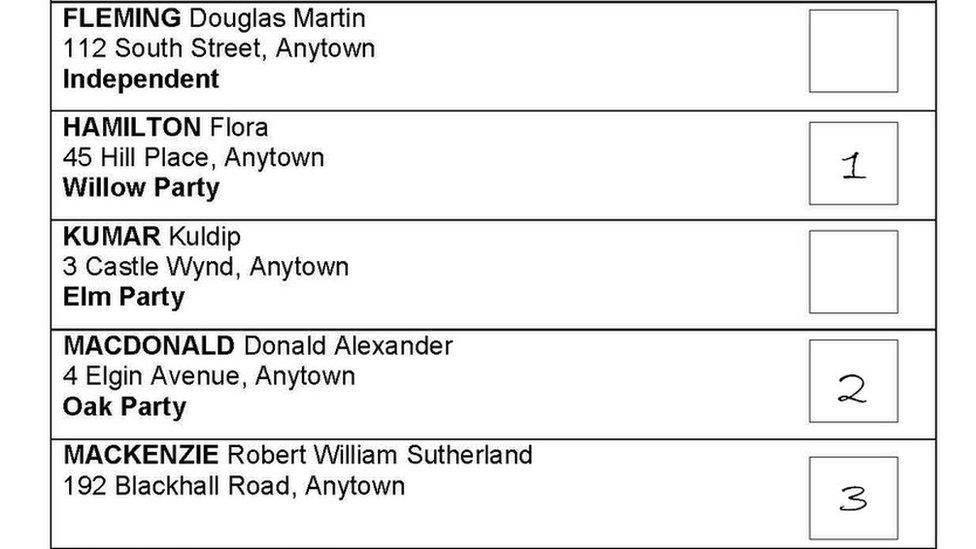

Scotland's council areas are chopped up into wards, each of which elects several councillors via the "single transferable vote" system. Voters rank candidates in order of preference, and a multi-round counting system whittles them down to those which are most popular overall.

Parties can choose to stand multiple candidates for these wards, if they think they are dominant enough in the area to win more than one seat.

The problem is that a lot of people turning up to vote on polling day are chiefly coming with a favourite party in mind, rather than specific research on each individual candidate.

And so when they look down the ballot paper, often they will whack their number one preference into the first box they come across from that party - even if there is another option further down.

At best, that second candidate will then be the voter's second preference - with a slimmer chance of being elected.

Data journalist Martin Rosenbaum studied two council areas, external in depth, and found candidates who came first alphabetically won on average more than twice as many votes as their party colleagues further down the paper - and were more likely to win a seat as a result.

Basically, Aaron Aardvark is going to have a better shot at securing his party's local seat than running mate William White.

In the 2022 contest, I counted more than 400 instances around Scotland of parties running more than one candidate in a single ward. And in 340 of them - just shy of 84% - those candidates were returned in alphabetical order.

This chimes with previous studies. BBC analysis tracked a similar pattern in 2017, and a report by Prof Sir John Curtice, external found the same thing happened in "no less than 80%" of possible cases in the 2012 election.

At present, candidates in local elections are listed on ballot papers in alphabetical order

What can be done about this?

A couple of different solutions have been suggested which could be tried out.

Candidates could draw lots to decide who gets to be top of the ballot paper - although this level of chance might feel just as unfair as going with alphabetical order.

Another solution would be to have half of the ballot papers in each ward presented from A to Z, and the other half from Z to A.

The order could also be scrambled up entirely in different batches of ballot papers - a system known as "Robson rotation" which is actually used for elections in Tasmania.

Given votes are counted electronically in Scotland's council elections, this in theory should not seriously impact the amount of time needed to tally up the results - although there would need to be new software.

There is also fairly broad appetite for reforms - a Scottish government consultation, external in 2018 found 81% of respondents in favour of making a change to counteract the "list order effect".

Are there reasons not to change?

Ministers asked the Electoral Commission to study the problem after the 2017 polls. The group's research found that, external in tests of different ballot papers, "the order of the candidates had no impact on voters' ability to find and vote for their preferred candidates".

However, it also heard concerns from groups representing disabled people that it could make voting less accessible.

The worry is that some people - like those who might have difficulty reading - familiarise themselves with a sample ballot paper at home before going to vote, preparation which would be in vain if they were confronted with a different layout in the polling station.

And while administrators were confident they could manage elections which use different papers, they raised concerns about the potential for increased costs printing and scanning them.

Some politicians have echoed these concerns.

Glasgow MP Alison Thewliss accepted it took "quite an effort" to beat the list-order effect when she made it onto the city council in 2012, but said, external changes "could make it harder for people with disabilities". She suggested that parties should do more to help explain the system to voters.

And Mhairi Hunter, who has just lost her seat on the same council as part of the 84%, said, external she "couldn't justify the additional expense to the taxpayer a randomised system would inevitably incur in producing and counting ballots".

"We just have to live with it," she said.

Some are nervous about any changes which could make things harder or more confusing for voters

Is this likely to change?

This is not a new issue. SNP backbencher Kenny Gibson has raised it repeatedly at Holyrood since 2007, while former local government minister Marco Biagi pondered reforms in 2014 but ultimately backed down.

The parliament debated the issue last term too, during the passage of the Scottish Elections (Reform) Act 2020.

A number of members pressed for randomised ballot papers, but it was ultimately concluded that "there is no point in simply replacing one set of problems with another".

Then-minister Graeme Dey said change was needed, but that "it must be change for the better and not have unwelcome unintended consequences".

He added: "It would be unrealistic to expect such a change to happen in the current parliamentary session, but it is work that must inevitably be done."

Mr Dey said the 2020 bill was "simply a step on the electoral reform journey", and fresh legislation is expected to be tabled at Holyrood this term as part of the SNP-Green partnership government agreement, external.

A number of MSPs from different parties have backed new reforms.

SNP MSP Bob Doris said "the time is right to review this once more", although he stressed that any changes should not lead to a rise in spoiled ballots.

And Labour's Paul Sweeney said the latest set of elections had "reinforced evidence in favour of why it would be fairer" to randomise the order.

The solution and the debate around it may ultimately be as complicated as the problem itself, but with a fresh set of data underlining the issue it looks likely to come under the microscope at Holyrood again.

Related topics

- Published9 May 2022