Nicola Sturgeon: The story so far of Scotland's first minister

- Published

A look back at Nicola Sturgeon's life in politics

As Nicola Sturgeon becomes Scotland's longest-serving first minister, BBC Scotland looks at how a girl from a west coast council estate rose to the nation's highest office.

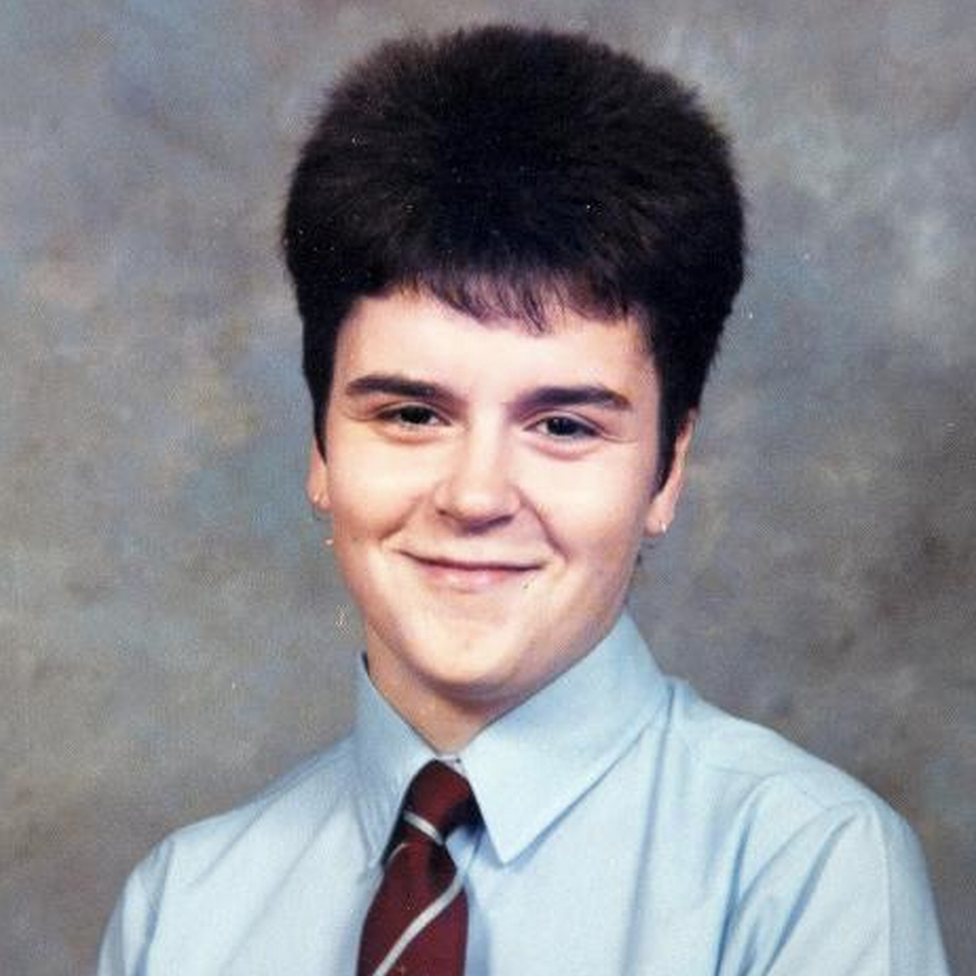

Born in Irvine, North Ayrshire, in 1970, she grew up during what she called "the dark days of the Thatcher era".

Nicola Sturgeon was born in 1970 in Ayrshire

She joined the SNP at 16, persuaded by the argument Scotland could only get the government it voted for if it was independent.

She was educated at Greenwood Academy

Her first taste of political campaigning was the 1987 election - after walking half a mile or so to the home of the local SNP candidate to offer help.

She went on to study law at Glasgow University before working as a lawyer.

Aged 22, when Ms Sturgeon first stood (albeit unsuccessfully) for office, in the 1992 general election, she was Scotland's youngest candidate.

The next general election, in 1997, saw Ms Sturgeon lose out on the Glasgow Govan seat to Mohammed Sarwar (the father of current Scottish Labour leader, Anas Sarwar).

Pictured here in 1992, at the Scotland United rally in Glasgow's George Square, with former MP George Galloway and singer and independence activist Pat Kane

Her entry into full-time politics came when she was elected to the new Scottish Parliament in 1999 as a Glasgow regional MSP.

She was 29, and has since admitted to being "a bit po-faced".

Ms Sturgeon has never revealed much about her private life. But in 2003, word spread that she was seeing SNP chief executive, Peter Murrell.

The pair had met when she was a teenager, at an SNP youth weekend in Aberdeenshire.

It would be 15 years before they stepped out as a couple, and they went on to marry in 2010.

Years of speculation about why the couple never had children followed. But she has since revealed she had experienced a miscarriage in 2011.

Nicola Sturgeon married Peter Murrell in 2010

After John Swinney stepped down as SNP leader, external in 2004, she announced her intention to run.

Kenny MacAskill (who has since left the party to join Alex Salmond's Alba party) was to stand as her deputy.

When asked if he would consider running for leader again, Alex Salmond memorably declared: "If nominated I'll decline. If drafted I'll defer. And if elected I'll resign."

But polling suggested Ms Sturgeon would lose and she and Mr Salmond decided to run on a joint ticket, external. They won.

Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon won the SNP leadership contest in 2004

She became Holyrood leader, facing Jack McConnell at FMQs every week, while Salmond was at Westminster.

The SNP went on to win the 2007 Holyrood election, external, with Ms Sturgeon winning Glasgow Govan from Labour's Gordon Jackson - the QC who went on to represent Alex Salmond during his sexual assault trial.

Her first big test in government came when she was deputy first minister and health secretary, as swine flu was declared a pandemic, external.

After the first UK cases were confirmed in Scotland, her incisive TV briefings became a fixture on news channels - good preparation for the hundreds of briefings she would go on to front during the Covid pandemic, over a decade later.

Further electoral success followed in 2011, when the SNP won an unprecedented majority at Holyrood.

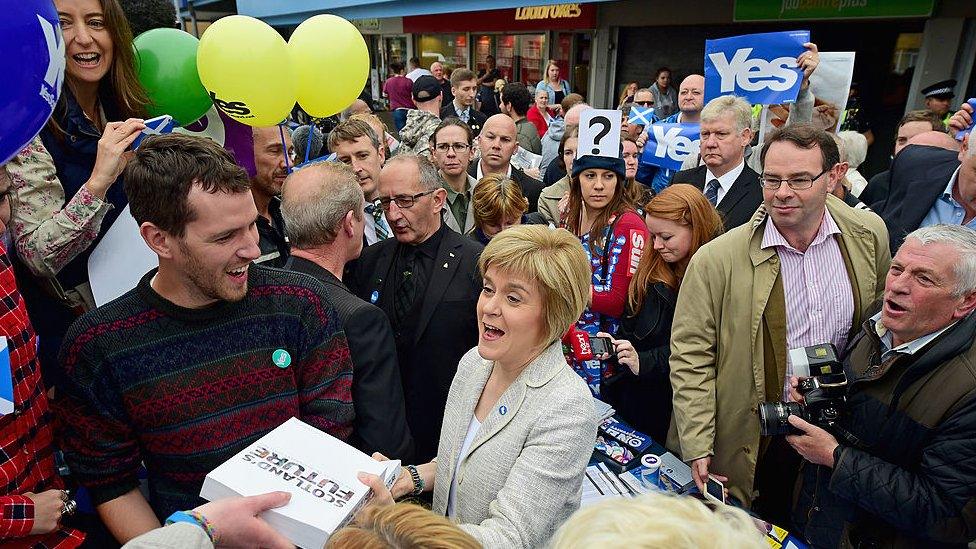

Nicola Sturgeon was responsible for the Scottish government's referendum planning

She then took on the job of "Yes Minister" - overseeing planning for the independence referendum.

But the Scottish electorate rejected independence, 55% to 45%, leading Alex Salmond to quit.

Ms Sturgeon took over from her mentor, after more of a coronation than a contest.

Party membership surged with her at the helm, and tens of thousands of new members signed up.

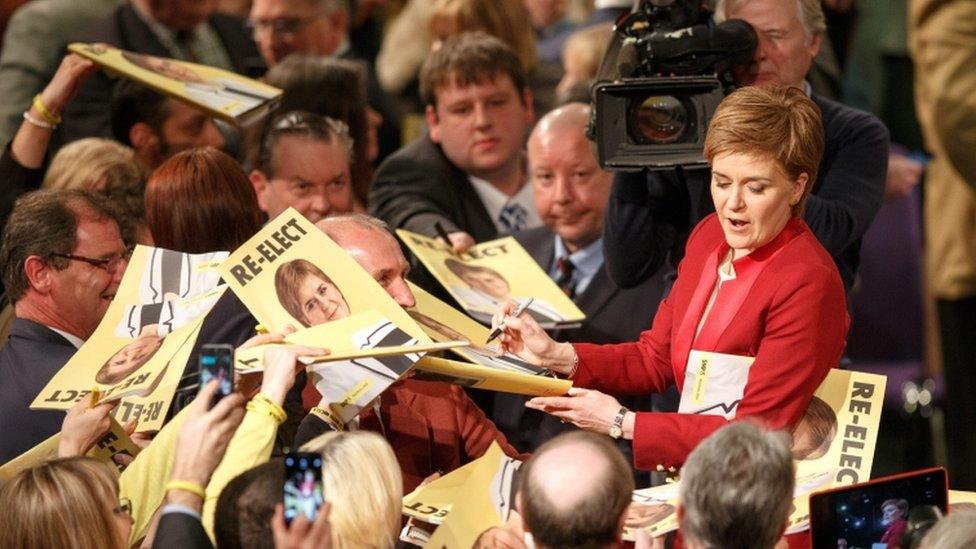

Electoral success followed the SNP campaigning on Sturgeon's profile

And the 2015 general election results were unprecedented, with the SNP taking 56 of the 59 seats in Scotland.

The trend continued in the 2016 Holyrood elections, with the SNP winning a record number of constituency seats.

The Brexit vote saw the UK as a whole vote to leave the EU by 52% to 48%. While in Scotland, the split was 62% to 38% in favour of remain.

The SNP said this "material change in circumstances" was enough to justify another independence referendum.

But the prime minister at the time, Theresa May, repeatedly insisted "now is not the time" for indyref2.

Ms Sturgeon won the backing of Holyrood, and sent a formal demand for a referendum.

However, the result of the snap general election was disappointing for the SNP. They lost a third of their seats, with Alex Salmond among the high-profile casualties.

Nicola Sturgeon was cleared of breaching the ministerial code

In August 2018, the Daily Record reported that allegations of sexual misconduct had been made against Alex Salmond - dating back to his time in government.

However, he successfully challenged the Scottish government's handling of the complaints in court. It decided the investigation was "tainted by apparent bias" and Mr Salmond was awarded more than £500,000 in legal costs.

But then in January 2019, Mr Salmond was arrested and charged with a string of sexual offences.

The case went to trial in March 2020, and Mr Salmond was acquitted of all 13 sexual assault charges - hours before the UK went into the coronavirus lockdown.

Mr Salmond later went on to claim there was a conspiracy against him orchestrated by those close to the first minister, and accused her of multiple rule breaches - including misleading Holyrood. She denied his claims and was cleared of breaching the ministerial code.

As well as damaging the pair's relationship, the affair caused a lasting rift in the SNP.

The first minister held hundreds of televised Covid briefings during the pandemic

The Covid crisis followed hot on the heels of the Salmond saga.

Many decisions following the first lockdown fell to the first minister, with her setting out her reasoning in hundreds of televised briefings.

Her government tended to favour a more cautious approach to relaxing restrictions.

The success of this approach is yet to be conclusively proved one way or the other, but a public inquiry into how the pandemic was handled will be held later this year.

After more than seven years in the job, Ms Sturgeon insists she has no plans to step down yet.

She has vowed to complete this parliamentary term as first minister, and promised another independence vote by the end of 2023 - although the UK government has refused to back a second vote.

All pictures copyrighted