Why is Scottish independence back in the spotlight?

- Published

Independence is never far from the surface in Scottish politics. It is the principle fault line. The great divide.

The question will persist unless and until a) independence actually happens or b) the public tire of the political parties that promote it.

Neither of those possibilities seem very likely anytime soon and so the debate continues.

It was largely put on hold during the pandemic but when the SNP won the Holyrood election in 2021, they did so having promised another referendum.

Together with the Scottish Greens who share power with them in the Scottish government, they have a majority in parliament for indyref2.

What they do not have is the explicit power to hold a vote.

That was overcome in 2014 through an agreement with the UK government, which transferred authority on a temporary basis to Holyrood.

It did so through what's known as a section 30 order.

The first minister has not yet formally asked for one of those this time, although UK ministers including Boris Johnson have made clear it would not be forthcoming.

Nicola Sturgeon's predecessor Alex Salmond seems to think she should make the request and use the rejection as a basis for her campaign.

She seems more cautious about giving the prime minister a formal opportunity to spurn indyref2.

The alternative, as set out in the SNP's previously published plan, is to test Holyrood's powers by introducing a referendum bill without UK agreement.

In 2014, Alex Salmond and David Cameron struck an agreement for power to hold a referendum to be transferred from Westminster to Holyrood

This approach anticipates that the bill would face challenge in the UK Supreme Court and that the Scottish government would argue its case there.

It would then be for judges to decide if Holyrood can hold a referendum or not.

On one side, the argument that there is no legal barrier to Holyrood consulting the public on any given issue and that a vote on independence would not be binding.

On the other, the argument that a "yes" vote would create the expectation that Scotland would become independent, fundamentally altering the UK constitution over which decision-making is specifically reserved to Westminster.

If the judges said no, the referendum would not go ahead because Nicola Sturgeon has specifically ruled out an illegal vote in the Catalan-style.

If the judges said yes, things could still get messy with the "no" side potentially boycotting a referendum on the basis that the process had not been agreed.

In reality, the only way to have a successful referendum is by agreement and at this stage there is not even consensus on the circumstances in which that should happen.

So, however certain Nicola Sturgeon says she is about indyref2 happening before the end of 2023, the basis for her confidence is not clear.

If she has some new initiative to break the deadlock, it remains well hidden.

The first minister has said she will make a statement to MSPs, probably this month, on how she plans to secure a referendum.

Distraction or opportunity?

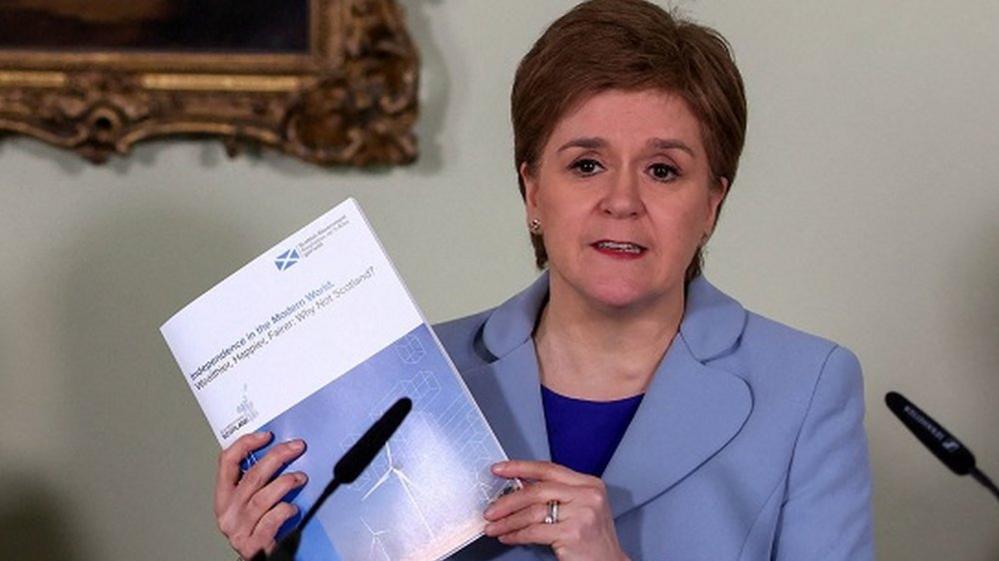

This week, for her, is less about the process and more about the principles behind her argument for independence. The whys rather than the hows.

It is a signal to her supporters that she means business and an effort to persuade others and build public pressure for another referendum.

There is no doubt that Brexit has fundamentally changed the circumstances in which Scotland voted back in 2014.

However, the upheaval leaving the EU has caused is - for some - an argument not to consider the bigger constitutional change that independence would bring.

To pro-UK parties like the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats, independence is a massive distraction from challenges like Covid recovery and the cost of living crisis.

To independence supporting parties, like the SNP and the Greens it is an opportunity for Scotland to decide how best to tackle these and other problems.

This is the beginning of a new phase of campaigning for and against independence and another referendum, rather than the start of a 2014-style referendum campaign.

Calling for a referendum does not mean it is actually going to happen but it does ensure the independence debate endures.

- Published14 June 2022

- Published14 June 2022

- Published13 June 2022