The indyref2 questions facing the Supreme Court

- Published

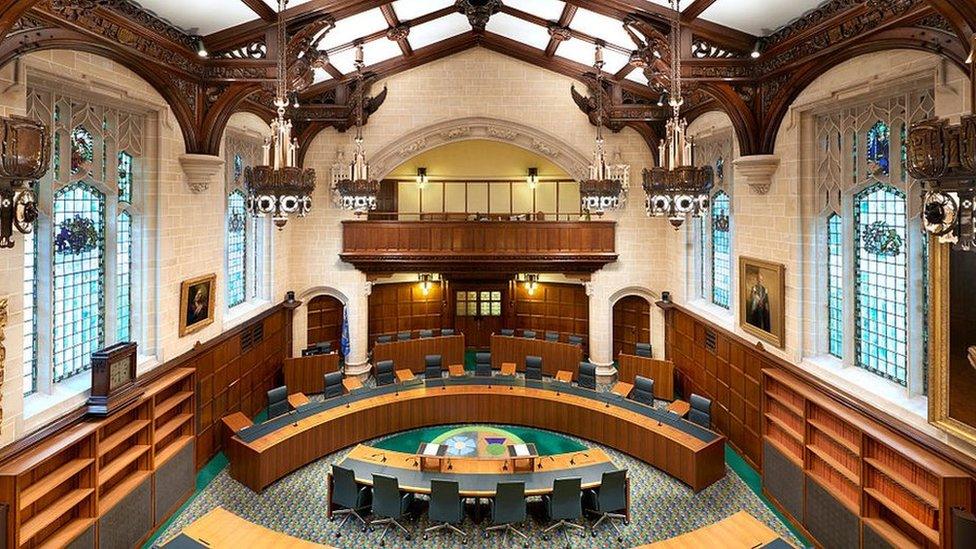

Inside the indyref2 Supreme Court case

The Supreme Court is to hear arguments about whether the Scottish Parliament can set up an independence referendum, with First Minister Nicola Sturgeon targeting a vote in October 2023. What are the key points likely to be, and will the court case help settle this constitutional row once and for all?

Why is this going to court?

In short, something needs to happen to break the deadlock between the Scottish and UK governments on independence.

The first minister wants to hold a fresh vote, has a pro-independence majority at Holyrood and has named a date. But successive prime ministers have insisted that "now is not the time" for a referendum.

This means a transfer of power like the one which underpinned the previous vote in 2014 is unlikely - so Ms Sturgeon wants judges to rule on whether MSPs could set one up without Westminster's backing.

There has been a long-standing debate over whether a referendum bill would be within Holyrood's powers, and the Scottish government's chief legal adviser - the Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain KC - has referred the issue to the Supreme Court.

Two days of arguments will be heard from 11 October, with a judgement expected to follow some months later.

Nicola Sturgeon proposes 19 October 2023 as date for referendum

What is the case for Holyrood having the power?

The Scotland Act states that MSPs cannot make laws which relate to "reserved matters" - topics which remain under Westminster control, and which include the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England.

It may seem strange to ponder whether an independence referendum bill relates to the Union. However, there is a school of thought that the simple act of seeking people's views would not in itself actually break up the Union.

Ms Sturgeon told MSPs that the referendum would be "consultative, not self-executing" - explaining that this meant that "a majority yes vote in this referendum will not in and of itself make Scotland independent".

The first minister points to the Brexit referendum as an example. The 2016 vote didn't drop the UK out of the EU automatically, but rather sparked years of negotiations and votes in parliament which resulted in a rather gradual break-up.

Ms Bain's written case, external essentially puts Ms Sturgeon's point into legalese, arguing that "the bill would not purport to alter or impede any legal rule constituting or affecting the union", adding that "the legal consequences of the bill are, relevantly, nil".

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain will lead for the Scottish government in court

What will the UK government's counter-argument be?

The UK government argues that judges shouldn't make a ruling at all, saying it is premature to consider a bill before it has passed through parliament. What if the court were to sign off the existing draft, only for MSPs to later amend it?

It is still possible that the court could agree with this, but judges want to hear the substantive arguments at the same time as those over this technical point.

The central point in the UK government's written case, external is a straightforward one: that Westminster is the sovereign parliament, and that it has clearly reserved the powers in this area.

Much of the debate about this in court is likely to focus on legal definitions, and what specific words mean.

The UK government side points to previous rulings which suggested that in order to "relate to" a reserved matter, a Holyrood bill must have "more than a loose or consequential connection" with it - and that a referendum bill would clearly meet this test when it comes to the Union.

On the idea of a "consultative" ballot, it says there is no secret about the Scottish government's intention - to "achieve independence for Scotland".

The UK government wrote: "A referendum is not, and is not designed to be, an exercise in mere abstract opinion polling at considerable public expense. Were the outcome to favour independence, it would be used... to seek to build momentum towards... termination of the union and the secession of Scotland."

Legislative disputes between the Scottish and UK governments are heard at the Supreme Court in London

Will the ruling settle the question of indyref2?

It would be foolish to speculate about how the judges will assess these arguments.

The current president of the court, Lord Reed, and his deputy, Lord Hodge, are both Scottish and indeed former Court of Session judges. They will be well versed in the matter of devolution, and have stressed the importance of judicial independence and impartiality.

In any case, the result of the case is not guaranteed to resolve whether or not there is an independence referendum in October 2023.

Should the Scottish government lose, they are not going to pack up and go home. In fact they have vowed to double down by treating the next general election as a "de facto referendum".

And equally, should the pro-Union side lose, it wouldn't necessarily stop them arguing that this is not the time for a referendum. It would put tremendous pressure on them, but they could argue that just because you can have a vote doesn't mean you should.

That pressure is really the point here. Ms Sturgeon still really wants to win an agreement with the UK government for a gold-standard, 2014-style process.

So no matter what the result is in court, the search for a political solution is likely to continue.

Do you have a question about Scottish independence? Use the form below to send it to us and we could be in touch.

In some cases your question will be published, displaying your name, age and location as you provide it, unless you state otherwise. Your contact details will never be published. Please ensure you have read the terms and conditions.

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question on this topic.

- Published28 June 2022

- Published23 November 2022