Nicola Sturgeon 'veering away' from voting in favour of assisted dying

- Published

Nicola Sturgeon has said she is "veering away" from voting in favour of assisted dying.

The former first minister said she had "rarely been as conflicted on any issue as I am on this".

The Lib Dem MSP Liam McArthur has introduced a bill to legalise assisted dying in Scotland.

MSPs are expected to have a free vote on the matter, with Mr McArthur saying "robust safeguards" are included in the bill.

First Minister Humza Yousaf has indicated that he does not support the proposed legislation, which is opposed by the Church of Scotland, the Catholic Church in Scotland, and the Scottish Association of Mosques.

Writing in the Glasgow Times,, external Ms Sturgeon said she had initially expected to back the legislation, but had instead found herself going the opposite way.

She said she had been "deeply moved" by the accounts of terminally ill people who wish to die at a time of their own choosing.

But Ms Sturgeon added: "Despite my expectations, the more deeply I think about the different issues involved, the more I find myself veering away from a vote in favour, not towards it.

"I worry that even with the best of intentions and the most carefully worded legislation, it will be impossible to properly guarantee that no-one at the end of their life will feel a degree of pressure."

Ms Sturgeon said she was worried the legislation could be the "thin edge of the wedge" and that society could lose focus on palliative care.

MSPs will get a "conscience vote" when it comes to assisted dying legislation. Party leaders won't tell their MSPs which way to go.

But the stance of influential politicians still matter.

Nicola Sturgeon remains one of the biggest names in Scottish politics, and it looks like she's inclined to not back the legislation.

She's giving off similar signals to the main party leaders - Humza Yousaf, Anas Sarwar and Douglas Ross have all indicated they have concerns.

So can this bill pass without the support of Holyrood's biggest names?

Well Liam McArthur, the MSP behind the assisted dying bill, believes there's been a "mood shift" amongst parliamentarians.

The talk amongst supporters is that Mr McArthur has done his maths, and is confident he has the numbers to get it through.

It feels like this legislation has better prospects than previous attempts, but many of Holyrood's main players seem unconvinced.

She said: "If we normalise assisted dying... then we will, as a society, lose focus on the palliative and end-of-life care and support that is necessary to help people, even in the worst of circumstances, to live with dignity."

Ms Sturgeon - who voted against previous bills that would have enabled someone to end their life - said that she had yet to reach a final decision and wanted to hear from her constituents.

Mr McArthur said he appreciated the issues raised by Ms Sturgeon and that he hoped to meet her and other MSPs "to allay their concerns".

He said: "Our current laws on assisted dying are failing too many terminally ill Scots and, despite the best efforts of palliative care, dying people too often face traumatic deaths that harm both them and those they leave behind."

Mr McArthur's bill would give people with an "advanced and progressive" terminal illness the option of requesting an assisted death.

They would need to have the mental capacity to make such a request, which would have to be made voluntarily and approved by two doctors.

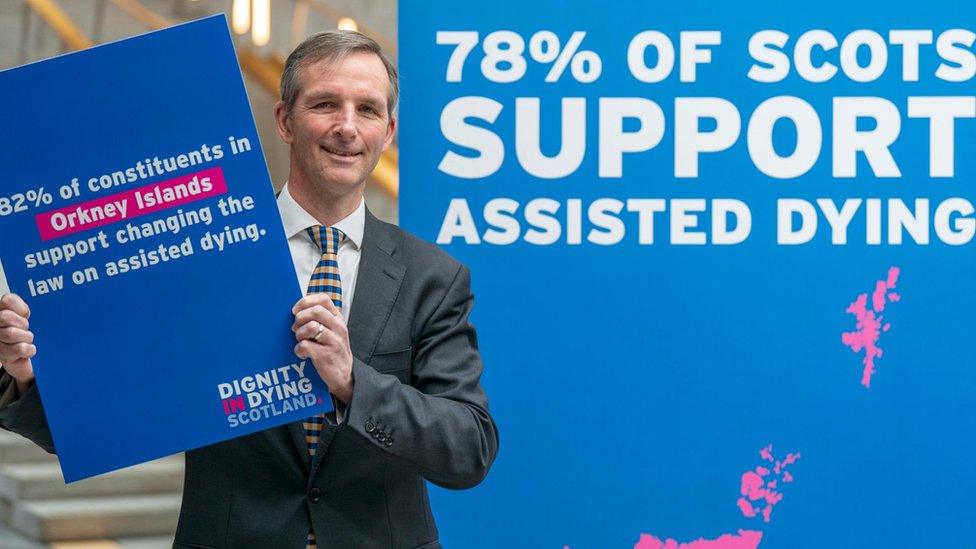

Liam McArthur believes there has been a significant "mood shift" on the issue

Only people aged 16 and over who have lived in Scotland for at least a year would be allowed to make a request, which would be followed by a mandatory 14-day "reflection period".

They would have to administer the life-ending medication themselves.

This will be the third time that the Scottish Parliament has considered the issue.

In 2010, MSPs rejected Margo MacDonald's End of Life Assistance Bill by 85 votes to 16.

The independent MSP, who had Parkinson's Disease, died in 2014 and the cause was taken up by Patrick Harvie of the Scottish Greens.

The following year, his Assisted Suicide Bill was rejected by 82 votes to 36.

In Scotland, it is not illegal to attempt suicide but helping someone take their own life could lead to prosecution for crimes such as murder, culpable homicide or offences under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

In England and Wales, the Suicide Act 1961 makes it an offence to encourage or assist the suicide or attempted suicide of another person. In 2015, the House of Commons decided against changing the law by 330 votes to 118.

In Northern Ireland, a similar offence is set out in the Criminal Justice Act 1966.

A number of countries have legalised some form of assisted dying - Dignity in Dying says more than 200 million people around the world have access.

This includes Switzerland, perhaps best known for its Dignitas facility, Australia, Canada, Spain, Colombia and 11 states in the US where it is known as "physician-assisted dying". Laws vary by country.

The title of Mr McArthur's bill - assisted dying rather than assisted suicide - reflects a change in approach from campaigners.

Critics such as Dr Fiona MacCormick of the Association for Palliative Medicine say the new terminology is "harmful and unhelpful," and that it uses "very euphemistic language to talk about suicide".

That was rejected by Mr McArthur, who said the bill was talking about people with a terminal illness, which meant that the fact they were going to die had already been established.

The MSP for Orkney Islands believes there has been a significant "mood shift" among his fellow parliamentarians since the issue was last debated and is hopeful that his proposal will be approved.

A new poll, carried out by Opinium Research for the campaign group Dignity in Dying, suggested that 78% of respondents in Scotland supported "making it legal for someone to seek 'assisted dying' in the UK".

But campaigners against the measure point to laws enacted in Belgium and Canada where qualifying criteria have been loosened over time, leading to a sharp rise in the number of "assisted" deaths.

Mr McArthur says his proposed law is not modelled on those "permissive and expansive models" but on places such as the US state of Oregon, where "the eligibility criteria has not changed at all" since becoming law in 1997.