Megrahi dies protesting Lockerbie bombing innocence

- Published

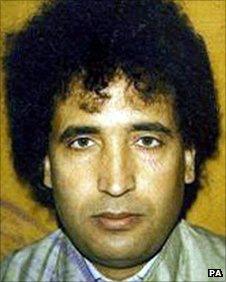

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was jailed in 2001 for the Lockerbie bombing

In the eyes of the law, Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi dies a mass murderer.

It is a verdict endorsed by many relatives of those who were killed in Britain's worst ever terrorist atrocity.

For them Megrahi will always be the Lockerbie bomber, the man who killed 270 people by blowing up a jumbo jet above a small town in southern Scotland.

Yet the Libyan goes to the grave protesting his innocence.

Guilty or not, his death - more than 23 years after the event which defined his life - does not draw a line under Lockerbie.

Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was born in Tripoli on 1 April 1952.

Like most of his compatriots he was a Muslim and his first language was Arabic although he also learned English, eventually acquiring more than a hint of a Scottish accent.

He spent time in the US and the UK but most of his life was lived in his Mediterranean homeland.

He was devoted, said his accusers, to the pursuit of state-sponsored terrorism, culminating in the destruction of a Boeing 747 - Pan Am flight 103 - in the skies above Dumfriesshire, killing all 259 passengers and crew on board and 11 people on the ground in Lockerbie.

And yet the word his supporters repeatedly used to describe him was "gentle".

'Wrongly convicted'

A "civilised, intelligent, caring man," said the former Labour MP Tam Dalyell. "Quietly-spoken...impeccably-mannered" and "humorous", according to his biographer John Ashton.

Both men believe that Megrahi was wrongly convicted.

By Mr Ashton's account, Megrahi was born into a very poor family, poverty which was "pretty typical" of 1950s Libya.

In the early 1970s he made one of several trips to the UK, to study marine engineering at Rumney Technical College in Cardiff.

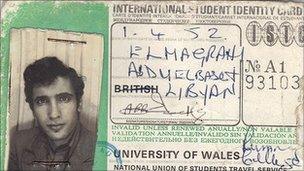

In the 1970s Megrahi studied briefly in Wales

The photograph on his student card shows a clean-shaven young man with tousled hair looking directly into the camera lens.

Within a year he dropped out of the course and returned home to a job with Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA), the state carrier.

There followed stints in the United States for training and Libya's University of Benghazi for study before Megrahi returned to the airline.

But there are two very different versions of his career.

Mr Ashton, who worked for Megrahi's defence team and knew him well, reports the Libyan's own version as follows.

He was a flight dispatcher who "rose up through the ranks," becoming head of airline security at LAA, where he was seconded to the secret service to organise training for airline security staff, his only involvement with Libyan intelligence.

His directorship of a company called ABH and a senior position with the Libyan Centre for Strategic Studies were "legitimate" roles.

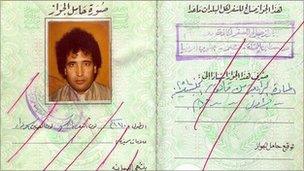

He admitted travelling on a false passport issued by the Libyan state but said this was because ABH was involved in the purchase of spare parts for aircraft in breach of international sanctions, not for any more sinister reason.

Bloody climax

The alternative version of Megrahi's career - advanced by the prosecution at his trial - alleged that his roles at the airline, the business and the think tank provided cover for espionage and terrorism on behalf of Libya's leader, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

Megrahi was accused of travelling to a string of countries in Africa, Europe and the Middle East to further the terrorist aims of the Libyan state.

Megrahi admitted using this false passport but denied he was a terrorist

He was said to be a cousin, or at least a fellow tribesman, of Said Rashid, a senior member of Libyan intelligence.

This career came to its bloody climax on 21 December 1988 when the bomb he had planted in a suitcase exploded 31,000 feet above Lockerbie.

Three years later Scottish prosecutors formally indicted Megrahi on charges of mass murder. He claimed that it came as a complete surprise.

His co-accused was Al Amin Khalifa Fahima, LAA's station manager at Luqa Airport in Malta, where the two men were alleged to have loaded the bomb aboard an Air Malta flight to Frankfurt before it was transferred to a feeder flight for Pan Am 103.

Eight years after the indictment was issued, under pressure from United Nations sanctions, Colonel Gaddafi handed over the two men for trial at a specially convened Scottish court in the Netherlands.

'Quiet man'

Their fate lay in the hands of three judges sitting at Camp Zeist near Utrecht.

Throughout the nine month-long trial Megrahi, wearing traditional Arab robes, sat in the dock listening attentively to an Arabic translation of proceedings.

His only son Khaled and one of his four daughters, Ghada, watched from the public gallery, separated from the dock by a bullet-proof screen.

Megrahi was freed from jail in August 2009 on compassionate grounds due to his prostate cancer

Megrahi exercised his right not to give evidence in his own defence but, in a television interview shown to the court, he told reporters: "I'm a quiet man. I never had any problem with anybody" and said he felt sorry for the people of Lockerbie.

The judges were not impressed. On 31 January 2001 Megrahi was convicted of 270 counts of murder. Fahima was acquitted.

Aphrodite Tsairis from New Jersey, whose 20-year-old daughter Alexia died in the bombing, summed up the feelings of many families of the victims, calling it a verdict of "state-sponsored terrorism", delivered by a "just and equitable court".

Most of the rest of Megrahi's life was spent in Scottish custody fighting that verdict, first at Camp Zeist, then at Barlinnie high security prison in Glasgow and finally at Greenock jail on the Firth of Clyde.

His first appeal was dismissed by a panel of five Scottish judges on 14 March 2002.

Compassionate release

His second appeal was making progress when, in the autumn of 2008, he was diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer.

The Scottish justice secretary, Kenny MacAskill, visited Megrahi in prison as he considered three options: releasing him on compassionate grounds, transferring him to Libya to serve out his sentence or keeping him in Scottish custody.

On 18 August 2009, without explanation, Megrahi formally abandoned his appeal and two days later Mr MacAskill ordered his compassionate release.

Megrahi lived his last days at home in Tripoli

The decision provoked an immediate storm of criticism which Scotland's nationalist government has weathered but which has not yet abated.

Scotland's last glimpse of Megrahi was of a stooped man wearing hidden body armour for fear of reprisals, slowly climbing aboard a Libyan plane at Glasgow Airport.

In Tripoli, Megrahi was given a rapturous official reception and for nearly three years he confounded experts, outraged Washington and embarrassed Edinburgh merely by staying alive.

And then in late summer, as the Arab spring belatedly took hold in Libya, his world began to fall apart again.

On 6 September a BBC team in the Libyan capital was taken to see Megrahi, apparently gravely ill, in his family home.

According to his son, he no longer had access to the expensive, specialised medical care which had reportedly been paid for by Colonel Gaddafi's government.

Khaled al-Megrahi told the BBC: "His body has become very ill and very weak."

Megrahi's death now does not resolve the big questions about Lockerbie.

If he was justly convicted, who gave his orders? Who helped him? And what was the motive?

And if Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi was innocent as he always claimed, who were the real culprits?