The 'exacting' architect forgotten by Scotland

- Published

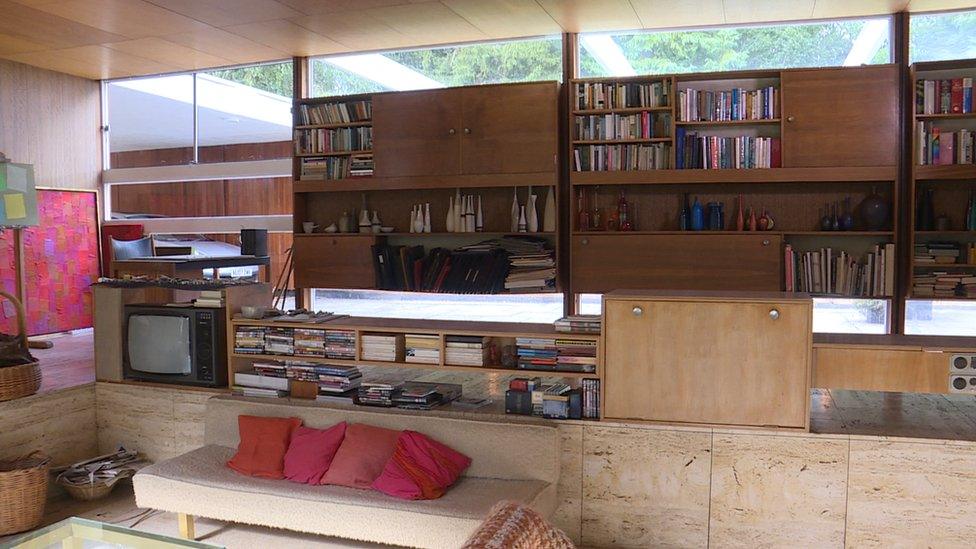

Bernat Klein's studio, designed by Peter Womersley and built in 1972

Peter Womersley has been described as an architect whose work you either love or loathe.

His designs are regarded as "exacting" - but also an "acquired taste".

The buildings are scattered across Scotland - ranging from a football stadium in Galashiels, to an organ transplant unit in Edinburgh, to a boiler house at a former district asylum near Melrose.

The modernist structures, characterised by concrete construction and strong geometric shapes, have influenced architects across the globe - but he is largely unknown in Scotland outside architecture circles.

He also designed numerous houses in the Scottish Borders, most of which are still being used as private homes.

Shelley Klein - who lives in the house designed for her father, the textile designer Bernat Klein - said she was unaware of the building's significance when she was younger.

"I was rather annoyed that I didn't live in a Victorian house like all my friends did. They seemed far more interesting to me when I was little," she told BBC Scotland.

"It's only now that I really appreciate how beautiful this building is."

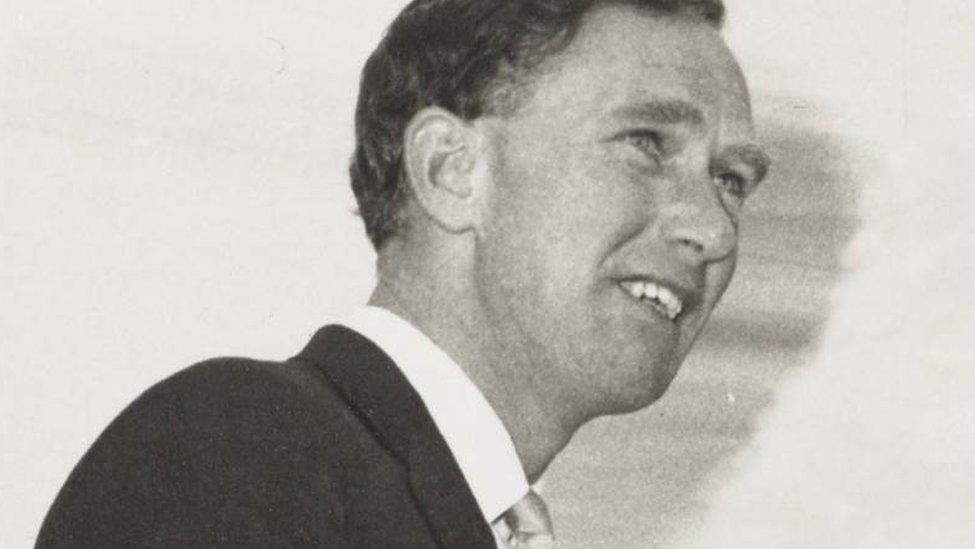

Peter Womersley was commissioned to design High Sunderland by his friend Bernat Klein

Womersley was born in 1923, studying architecture at the Architectural Association in London after being called up for service in World War Two. He was admitted to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1952.

His first commission was to build a house, Farnley Hey, for his brother John near Huddersfield, which won a RIBA medal in 1958.

Klein and his wife came across the house in the 1950s and were instantly impressed, commissioning Womersley to design their home, High Sunderland, near Selkirk. The architect also designed a studio for Klein nearby in 1972.

Klein's daughter said it was their subsequent friendship that brought Womersley up to the Borders frequently. He built a home for himself at Gattonside, near Tweedbank, after falling in love with the Borders landscape.

"He has not really been lauded at all for his work. He's almost forgotten outside a small set of architects who obviously appreciate his work. I'm rather pleased he's getting some recognition now - I think it's overdue," she said.

"We've got his wonderful cache of extraordinary buildings here in the Borders so we should celebrate and treasure them."

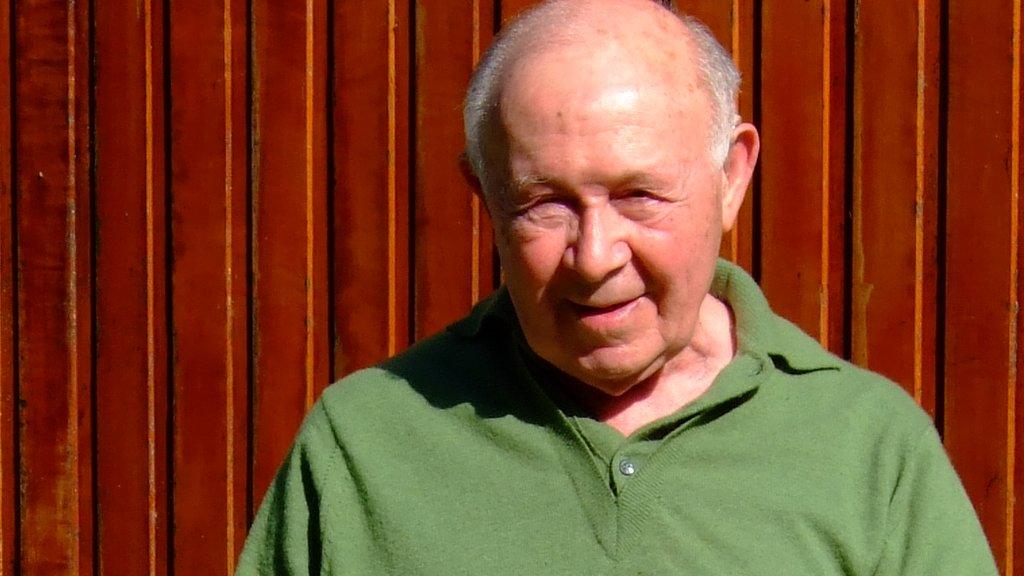

Peter Womersley died in 1993

The architect's buildings are characterised by concrete and strong geometric shapes

A few miles down the road in Galashiels is one of Womersley's best known works - the football stand he designed for Gala Fairydean FC in 1963.

The A-listed stand is built with concrete and has a cantilevered structure that creates the effect of a floating canopy. The club's match secretary, Robert Fairburn, said the terrace provoked a "mixed bag" of reactions - being either liked or loathed.

"Some people think it resembles something out of the Soviet Union in the 1960s. But then again we get visits from architects just spontaneously turning up at the ground and from football supporters the length and breadth of the country just wanting to see what is an iconic football grandstand," he said.

"There's nothing like it anywhere else in the world we think."

The football stand pushed the limits of what could be engineered out of concrete at the time

But the 52-year-old stand is starting to crumble and the club is working with Historic Environment Scotland on a programme of works that it is hoped will help preserve it for future generations of fans.

The structure, built by engineers Ove Arup and Tom Ridley, was upgraded to its A-list status in 2013.

Simon Green, an architectural historian for Historic Environment Scotland, said the stand was typical of the designs produced by Womersley, who died in 1993.

"It was a revolutionary idea, working closely with Ove Arup, and pushing engineering of concrete into its absolute highest possible abstraction.

"He pushes everybody and Tom Ridley writes very eloquently about being forced and contorted to design this very, very high-spec building - which in effect is a for a modest small football club in a small Borders town.

"But being Peter he pushed and pushed and created something unique."

'Acquired taste'

Mr Green is leading a seminar and tour of Womersley's work in October, which he hopes will raise the profile of an architect almost unknown to the wider public in Scotland.

"Womersley was always fascinating because every building he built, he built with passion and integrity - to the infuriation of his clients and his friends and other architects. He was exacting," he said.

"His body of work is quite small but each one has its own particular character and style."

Mr Green said he accepted Womersley was an "acquired taste" who would never penetrate the mainstream like Charles Rennie Mackintosh has done.

"I don't think unfortunately it will ever reach the heights of Mackintosh devotion," he said.

Womersley designed the Nuffield Transplantation Unit at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh

Despite this, the historian believes it is crucial that Womersley's buildings are still used as they were intended by the architect.

"The idea that a building can still be used for its original purpose is really exciting - and I think that has to be encouraged and preserved as long as possible.

"That's the excitement of most of his houses as well, as they have stayed as residences. Particularly High Sunderland which Shelley Klein is preserving very much as her father lived in it."

For Ms Klein's part, she says she still loves living in a house designed by Womersley.

"It still instils me with joy and it did so for my father throughout his life - he loved this building. Every day he would get pleasure from it, as do I," she said.

- Published23 April 2014

- Published2 December 2013