The 'selfish waster' who now runs a monastery

- Published

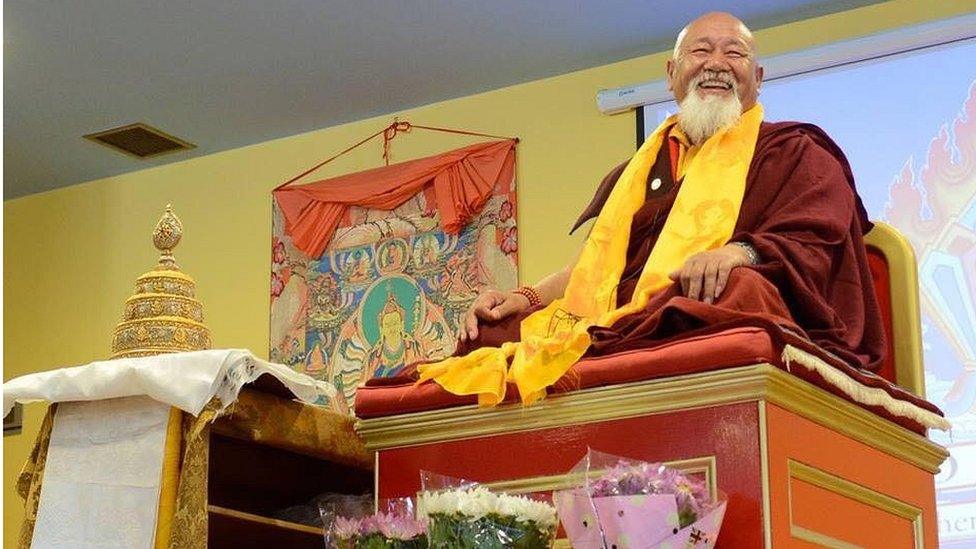

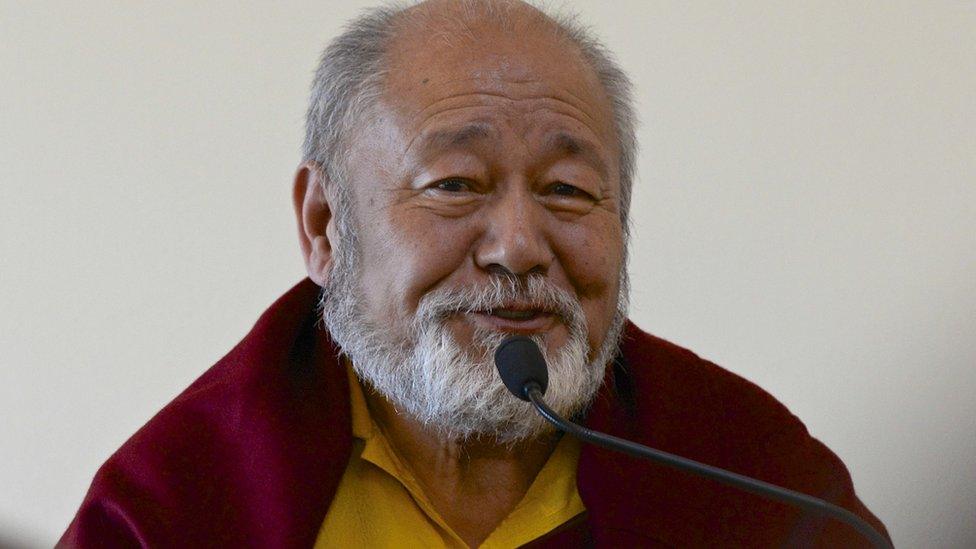

Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche is the abbot of the Samye Ling monastery in southern Scotland

As a young man, Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoche was a "selfish waster" but his journey to Scotland has seen him take a different path.

He was born in an "idyllic" village in Tibet but constantly rebelled against his family, experiencing wild times around the world for many years.

Now he calls a quiet corner of southern Scotland his home, where he is the abbot of the Samye Ling Buddhist monastery near Eskdalemuir.

'Idyllic place'

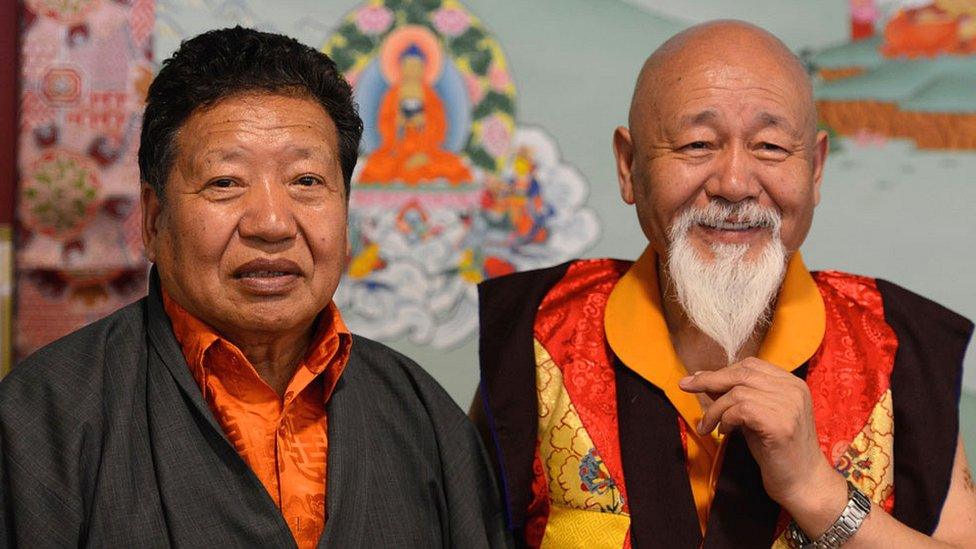

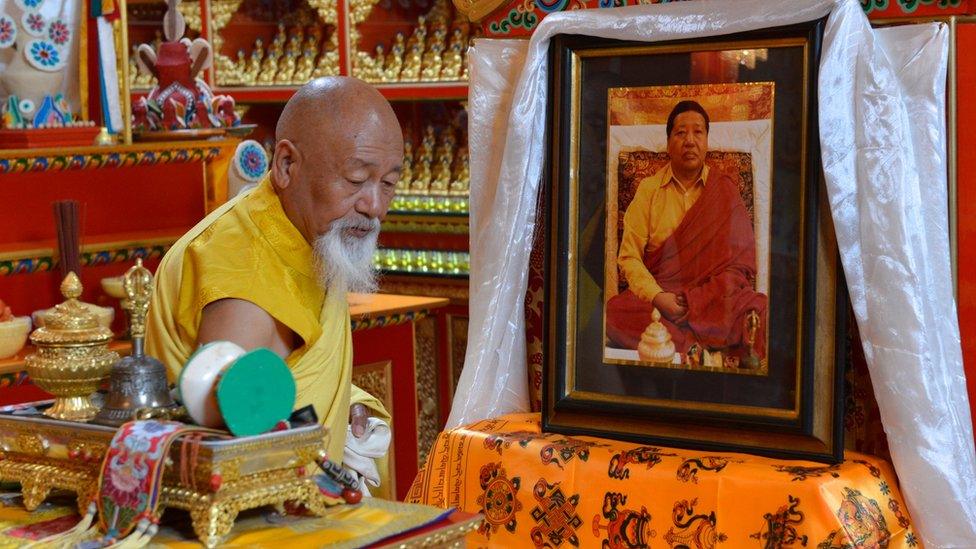

In his youth he was angry with his brother, Akong Rinpoche (left), after ending up in his monastery

He was born Jampal Drakpa in 1943 and grew up in the tiny village of Darak in Tibet a place where, he said, "you can suffer frostbite and sunstroke in the same day". Ideal preparation, perhaps, for living in Scotland later in life.

He paints a picture of a simple, tough but happy childhood.

"I was born in a very idyllic place," he said. "No education was given - children had the whole day to play around so they didn't have to learn anything - which was fortunate or unfortunate, I don't know."

However, at age 12, he was sent to join his brother Akong Rinpoche who was already running a Buddhist monastery.

"In Tibet it was expected I would join him when I learn all the knowledge and I will become like his treasurer," he says.

Except, as a young boy, he was reluctant to accept that fate.

"It is one of the coldest parts of Tibet," he said. "There are no trees, it is like the whole area is so white and so wild and I had no knowledge of anybody. I was so angry with my brother, I think I wanted to escape to my family's home."

Dodging bullets

Lama Yeshe managed to escape to India as a teenager

His chance to get away from the monastery came three years later but in dramatic circumstances.

The arrival of the Chinese army meant that in 1959 he had to make an arduous escape through the Himalayas to India.

"We had to go from mountain to mountain and there was no road, it was the middle of winter so we had to give up our horses and most of our possessions," he says. "We suffered so much."

After months of travelling, he was one of a handful to manage to cross a river - dodging bullets as they went - and eventually reach India.

He lost one brother to TB after the escape and had to undergo a major operation himself.

However, he said it had not changed his character as he remained "selfish and full of pride" and, later, "surly and miserable".

His leisure activities in India included "gambling, movie-going and chatting up young women" - not obvious monk material.

Later in life he would add to this a love of cars - despite having never seen one until he was 15. He survived a string of crashes.

'Shocked and unhappy'

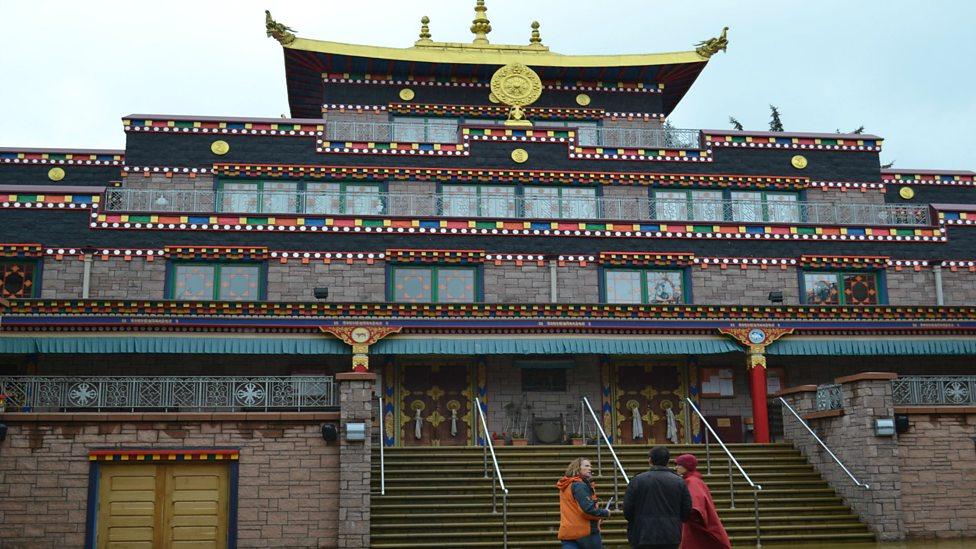

Over the years Samye Ling has developed into a "beautiful temple" from unpromising beginnings

It would not be until 1969 that he made the journey to Scotland to join his brother Akong at the Tibetan Buddhist centre he was setting up in Dumfries and Galloway.

His early impressions were not great.

"When I came to Eskdalemuir that time was a disaster time," he says.

"All the people were taking drugs, alcohol, they were stinking and smelly. They were not like human beings - I was totally shocked and unhappy."

He would not attend teaching and was "moany" about his situation.

"I was totally blaming my brother as though he was the cause of all my suffering," he says.

"He never told me what to do because if he said you turn right I turned left, and if he said you turn left I turned right. I wanted to do everything the opposite of what he tells me."

'Rolling with pain'

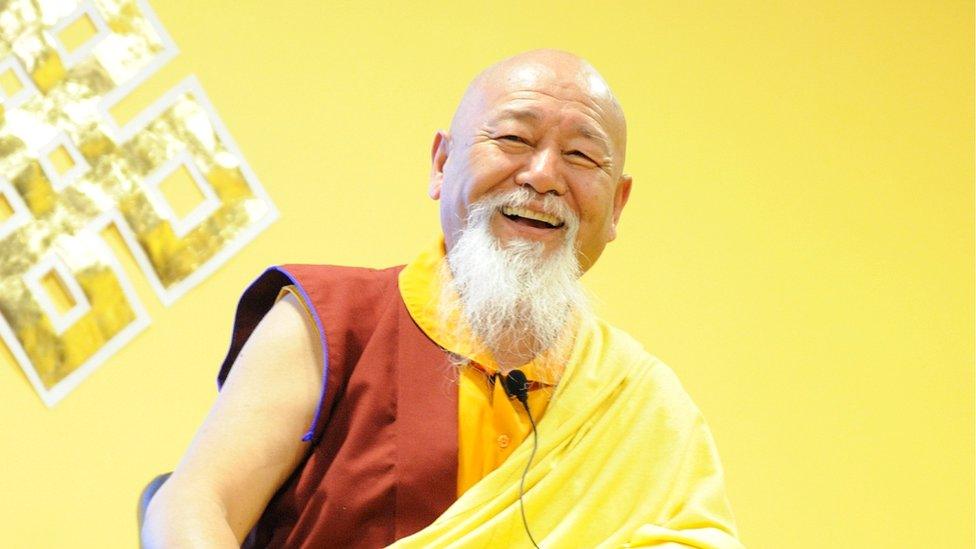

Lama Yeshe vowed to make his brother proud

There was one incident, more than any other, which changed his attitude.

After a fishing trip to the Orkney Islands with a friend his brother saw pictures of their catch, which broke the fundamental Buddhist precept against killing.

Akong was "devastated" and said he felt he had let their parents down.

"My heart was really rolling with pain," said Lama Yeshe. "Always I had fought back but then deep down in my mind I made a vow - until I make you proud I will never come back."

It would lead, eventually, to his ordination as a Buddhist monk.

But first there were "wild days in the USA", when he turned his attention to "self-indulgence, materialism and worldly pleasure".

He went to nightclubs, "discarded women with no thought for their feelings" and drank whisky until he passed out.

Until one night he got so drunk he realised he had to change.

'Paying him back'

Lama Yeshe vowed to make his brother proud

After several years in America, he returned to Scotland in 1985 to find Samye Ling transformed with a "huge and beautiful temple" under construction.

A decade later, he would become its abbot.

His brother, Akong, was stabbed to death in China in 2013 but Lama Yeshe has continued his work at Samye Ling.

"After his passing I take care of all his centres," he says.

"They have all grown in size. I feel that I am now paying him back."

He also hopes that his own experiences - shared through his book, From A Mountain in Tibet - might help others.

He said many of his European students told him about the problems they had encountered in their lives, or difficulties with their families.

"So I said to them: 'You have never had a problem. You read my book and we can see who suffered more. You can't compete with me'," he says.

"I want everybody to know how bad I was," he added.

"I say nowadays there are many teachers who become famous and they claim they are special human beings. I am saying: 'I was nobody'.

"My motivation, everything I do, is to help others."

It's a long way from the "selfish waster" that he describes himself as being in his younger days.